Information Inquiry and Instructional Analysis

At the completion of this section, you should be able to:

- Compare and contrast information inquiry models

- Identify key topics in information literacy

- Create an instructional analysis.

Begin by viewing the class presentation in Vimeo. Then, read each of the sections of this page.

Explore each of the following topics on this page:

- Information Inquiry

- Information Search and Inquiry Models

- Topic in Information Inquiry

- Instructional Analysis

- Resources

Information Inquiry

To develop effective instruction, it's important to have a clear vision of the content being taught. As subject matter experts in the area of information, librarians are in a unique position. Our job is to help others understand the information inquiry process, how to conduct an information search, and how to use a wide range of resources. Teaching these information skills requires a detailed analysis of the content and processes that go into understanding and using information.

Information inquiry involves the processes of searching for information and applying information to answer questions we raise personally and questions that are addressed to us. Techniques for gaining meaningful information may involve reading, listening, viewing, observing, interviewing, surveying, testing and more.

Meaningful information application comes from analysis of information need, analysis of information gained, and synthesis of information to address the need in the most efficient and effective manner possible. The five interactive components of information inquiry are (Callison, 2006):

Meaningful information application comes from analysis of information need, analysis of information gained, and synthesis of information to address the need in the most efficient and effective manner possible. The five interactive components of information inquiry are (Callison, 2006):

- questioning

- exploring

- assimilation

- inference

- reflection

Questions in information inquiry may range from the most basic, factual reference questions to the most complex puzzles of life for which there are no answers. Questions tend be tied to one or more of three information environments: Personal, Academic, and Workplace.

Read!

Read!

Explore Graphic Inquiry.

This online workshop explores how graphics can be built into the information inquiry process. It also provides a great example to explore. If you want to learn more, read the book Graphic Inquiry by Annette Lamb and Daniel Callison (2012).

Many educators view information inquiry as the foundation of all "traditional content areas." Rather than focusing on individual skills, teachers prefer to use a problem-solving or inquiry-based approach to the process of working with information and creating communications. Others focus on a subset of skills and call these study or research skills.

A Brief History of Information Inquiry Models

Researchers and practitioners have designed models to illustrate how teachers and learners act in information inquiry situations. Other models have been developed for processes such as the scientific process, thinking, and writing.

During the 1980s educators and librarians experienced a surge of interest in information skills. At the peak of the HOTS (Higher Order Thinking Skills) movement, educators were finding that a process approach to information inquiry could be found across disciplines.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, informational skills became a focus of many researchers. Much of this research was shared at the annual Treasure Mountain Research Retreats.

In the 1990s, the models began to stress the ongoing cycle of inquiry. Rather than a series of discrete steps, educators began to see the process as involving recursive elements and ongoing questioning, exploration, and investigation.

Linear vs Recursive Approaches

Information literacy models generally lead users through a series of steps while conducting research. These models are useful in scaffolding the activities of novice information seekers. Some researchers have criticized these approaches because of their linear nature and lack of opportunity for spontaneity. However recent studies show that these models do provide for recursive elements and chances for flexibility.

According to Sandy L. Guild (2003) in Curriculum Connections through the Library edited by Stripling and Hughes-Hassell, "recursion, or this repeated application of a research procedure to the results of a prior procedure, is invoked any time the research determines that the emerging complex of relationships has undeveloped area, logical errors, or incongruities" (p. 141). Unfortunately, when educators teach about the research process it's often "presented in a fashion that leads students to assume that the process is linear" (p 142). In the "real world" research is messy. Students often revisit steps over and over again.

In the blog The Bottom of the Pile (2009), Pam Meiser discusses the importance of recursion in learning. She encourages students to think aloud about their process. However she didn't always take this approach. In the past, she used a linear process but found that students were frustrated by the real-world of research,

"a student may have started an animal report on a koala. He wrote down some questions, found sources, and took notes. Then, when that student and I sat down to talk about and organize the notes, I found that he had written the word "marsupial" many times, but had no idea what it meant. I sent that student back to his sources to find the answer. He didn't even know enough about the subject to have written "What is a marsupial?" as one of his original research questions. Nor did he realize that not knowing what a marsupial was, would probably inhibit his understanding of many aspects of the koala."

"What I should have done, and will do in the future, is to include this self talk or think alouds to the research process. I should have explained to the student that it's normal to have to go back and look for more information about your topic, even after you've "completed" your research. I am also going to look, or create, visual models of research that show a more circular or recursive process. I have often seen models for the writing process that are more circular."

Read!

Read!

Read Modeling Recursion in Research Process Instruction by Sandy L. Guild.

How does the idea of recursion fit into specific information instruction topics across educational situation?

According to Erdelez, Basic, and Levitov (2011), "information encountering (finding information while searching for some other information), is a type of opportunistic discovery of information that complements purposeful approaches to finding information. Erdelez, Basic, and Levitov (2011) found that none of the information literacy models they studied make explicit reference to information encountering, however all of the models could accommodate this type of information experience.

Teaching and Inquiry Models

Most educators agree that teaching information literacy as a process is the best approach to addressing the essential knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

It's helpful if a library or school can agree on a single model or at least the general steps in information inquiry. This way, the librarians and content-area faculty can all be using the same vocabulary with students. It's also helpful for students to see that information inquiry crosses the entire curriculum. Rather than forming a special committee, the librarian might work through the district curriculum committees or university departments to address this issue.

Try It!

Try It!

We've done a comparison of many of these information processing or information inquiry models using Inspiration. This comparison is available in PDF format. Also, check out Katie Baker's comparison.

Explore the various models, then create your own chart. Use this to think about your own original model for the inquiry process.

How successful are instructional librarians in preparing their students? It depends on the program and approach. It's important to conduct research to determine whether the chosen model or approach is effective.

Read!

Read!

Read The Research Process and the Library: First-Generation College Seniors vs. Freshmen by Elizabeth Pickard and Firouzeh Logan (2013).

Think about how you could determine whether your chosen approach is effective.

Information Search and Inquiry Models

This page explores the most popular information inquiry models. Many of these websites contain examples and sample projects. The resources will guide you to resources designed for teachers and links for students.

5-As by Jukes

Ian Jukes focuses on the 5 As of information processing. These include:

- Asking - key questions to be answered

- Accessing - relevant information

- Analyzing - the acquired information

- Applying - connect the information to a task

- Assessing - the end result and the process

8Ws of Information Inquiry

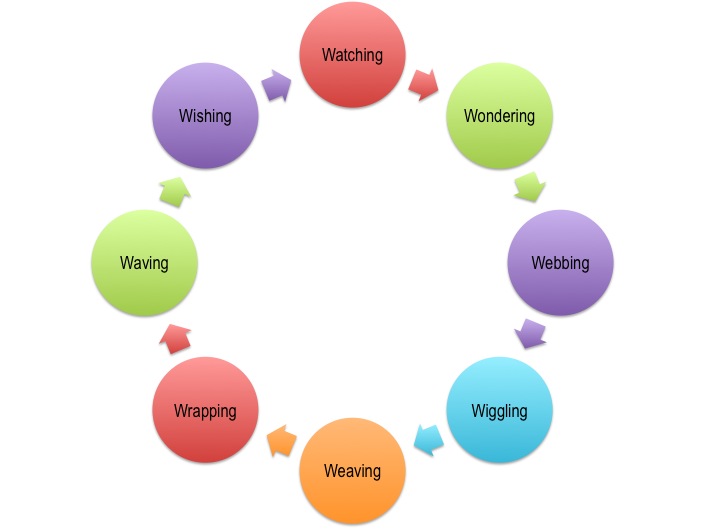

Children don't just "do" information, technology, and Internet. An inquiry or project-based learning environment involves wondering about a topic, wiggling through information, and weaving elements together. Each student learns and expresses themselves in a unique way.

This model was developed by Annette Lamb in the early 1990s. It was published in the book Surfin' the Web: Project Ideas from A to Z by Annette Lamb, Larry Johnson, and Nancy Smith in 1997 and in an article called Wondering, Wiggling, and Weaving: A New Model for Project and Community Based Learning on the Web.

Read!

Read!

Read Wondering, Wiggling, and Weaving: A New Model for Project and Community Based Learning on the Web by Annette Lamb, Larry Johnson, and Nancy Smith (Learning and Leading With Technology, 1997, 24(7), 6-13.

Alliteration was used to stimulate student interest and focus on the student's perspective. You're probably familiar with the 5Ws (who, what, when, where, and why), here are 8 new ones. You can view a print version of the 8Ws model using the PDF file.

Explore each of the 8W's. Click on the link for each of the Ws below to read about about this aspect of inquiry.

Explore each of the 8W's. Click on the link for each of the Ws below to read about about this aspect of inquiry.

- Watching (Exploring) asks students to explore and become observers of their environment. It asks students to become more in tune to the world around them from family needs to global concerns.

- Wondering (Questioning) focuses on brainstorming options, discussing ideas, identifying problems, and developing questions.

- Webbing (Searching) directs students to locate, search for, and connect ideas and information. One piece of information may lead to new questions and areas of interest. Students select those resources that are relevant and organize them into meaningful clusters.

- Wiggling (Evaluating) is often the toughest phase for students. They're often uncertain about what they've found and where they're going with a project. Wiggling involves evaluating content, along with twisting and turning information looking for clues, ideas, and perspectives.

- Weaving (Synthesizing) consists of organizing ideas, creating models, and formulating plans. It focuses on the application, analysis, and synthesis of information.

- Wrapping (Creating) involves creating and packaging ideas and solutions. Why is this important? Who needs to know about this? How can I effectively convey my ideas to others? Many packages get wrapped and rewrapped before they're given away.

- Waving (Communicating) is communicating ideas to others through presenting, publishing, and sharing. Students share their ideas, try out new approaches, and ask for feedback.

- Wishing (Assessing) is assessing, evaluating, and reflecting on the process and product. Students begin thinking about how the project went and consider possibilities for the future.

Big6™ by Eisenberg and Berkowitz

Michael B. Eisenberg and Robert E. Berkowitz have been promoting their approaches to information processing for nearly 20 years.

Michael B. Eisenberg and Robert E. Berkowitz have been promoting their approaches to information processing for nearly 20 years.

The Big 6 is an information problem-solving approach developed by Michael B. Eisenberg and Robert E. Berkowitz. It is the most popular model for information skills. It includes the following steps:

- task definition

- information seeking strategies

- location and access

- use of information

- synthesis

- evaluation

Although presented in steps, Eisenberg and Berkowitz stress that the model doesn't need to be linear and allows for recursive loops.

Try It!

Try It!

Explore the The Big 6 website. The Big 6 model focuses on problem-solving across the curriculum. The website provides background information and lots of lesson and activity ideas. Go to the Overview to see the steps in detail.

Notice how the website provides a wealth of information for librarians implementing this approach.

Watch!

Watch!

View Big 6 Introduction (1:00).

Bob Berkowitz provides an introduction to the Big 6 information problem-solving process.

Use of this video clip complies with the TEACH act and US copyright law. You should be a registered student to view the video.

Read!

Read!

Read The Big Six Information Skills As a Metacognitive Scaffold: A Case Study by Sara Wolf, Thomas Brush, and John Saye. (SLMR, 6, 2003).

Building Blocks of Research

Debbie Abilock states that "information literacy is a transformational process in which the learner needs to find, understand, evaluate, and use information in various forms to create for personal, social or global purposes."

Abilock's model focuses on a set of core thinking and problem-solving meta-skills across disciplines. The model includes the following steps:

- Engaging

- Defining

- Initiating

- Locating

- Examining, Selecting, Comprehending, Assessing

- Recording, Sorting, Organizing, Interpreting

- Communicating, Synthesizing

- Evaluating

In her website, Abilock provides resources to go with the Building Blocks of Research.

DIALOGUE by InfoOhio

The DIALOGUE model (1998) involves the following areas that spell DIALOGUE:

- Define - Explore/Identify the need for the information; Determine the basic question

- Initiate - "Distressing ignorance"

- Assess - Identify keywords, concepts, and possible resources; Consider information literacy skills; "Tapping prior knowledge" and "Building background"

- Locate - Identify possible sources of information; Develop a search strategy; Locate and retrieve available resources

- Organize - Identify the best and most useful information sources Evaluate the information retrieved

- Guide - Search log or journal Student assistance and review; Educator assistance and review

- Use - Determine presentation format Present results; Communication information

- Evaluate - Evaluate the project/results Evaluate the process; Assess the teaching and learning

Evidence-Based Medicine

The process of evidence-based medicine including the following steps:

- Asking focused questions

- Finding the evidence

- Critical Appraisal

- Making a Decision

- Evaluating Performance

- Designing Research

To learn more about the steps of EBM, go to the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine website.

FLIP IT! by Yucht

Created by Alice H. Yucht, this decision-making framework can be used for both personal and professional information processing needs. FLIP IT focuses on four strategic markers. These include:

- Focus - guideposts for the quest I'm on (specifying)

- Links - connections to help me proceed (strategizing)

- Input - implementing the information I find (sorting, sifting, storing)

- Payoff - putting it all together for a profitable solution (solving, showing, sharing)

- IT! - Have I demonstrated Intelligent Thinking throughout the process?

Explore the FLIP IT! guide at Alice in InfoLand. Browse the resources on FLIP IT! It includes resources and teaching materials.

Information Literacy Cycle

The Information Literacy Cycle developed by the NHS Education for Scotland is geared toward health care professionals. It contains seven phases:

- question

- source

- find

- evaluate

- combine

- share

- apply

To learn more, go to Information Literacy Cycle. Be sure to check out their scenarios.

Information Search Process (ISP) by Kuhlthau

In the 1980s and early 1990s many information models were developed. The Information Search Process (ISP) by Carol Kuhlthau is unique because it is based on research specifically designed in this area. Studies from various disciplines, but particularly writing were used to support her model.

Kuhlthau observed the reactions of students, examined strategies such as journaling, case studies, interviewing, and tracked student progress. These observations make her approach to information inquiry particularly rich. Beyond the basic model, her research stresses the attitudinal and emotional aspects of the inquiry process. For instance, she talks about the importance of providing students with a "invitation to research" that encourages students to visualize the possibilities. She also discussed the "dip in confidence" experienced by learners as a natural part of inquiry.

The Information Search Process Model

Carol Kuhlthau's library research process was published in her 1985 book Teaching the Library Research Process which was updated in 1994. The process includes seven stages. Within each stage is a task, thoughts, feelings, actions, and strategies. An updated version of this process was renamed the Information Search Process (ISP). The process includes the following stages:

Initiating a Research Assignment

Feelings: apprehension, uncertaintySelecting a Topic

Feelings: confusion, sometimes anxiety, brief elation, anticipationExploring Information

Feelings: confusion, uncertainty, doubt, sometimes threatFormulating a Focus

Feelings: optimism, confidence in ability to complete taskCollecting Information

Feelings: realization of extensive work to be done, confidence in ability to complete task, increased interestPreparing to Present

Feelings: sense of relief, sometimes satisfaction, sometimes disappointmentAssessing the Process

Feelings: sense of accomplishment or sense of disappointment

Feelings, Thoughts, Actions and the Uncertainty Principle

One of the most interesting aspects of Kuhlthau's work is her emphasis on the attitudes and behaviors of students during the process. She states that "in an ideal situation, students begin to search for information because they want to know more about something that is interesting or troubling. In such cases, the motivation to seek information arises naturally out of the person's own experience."

She finds that although students often start a project with enthusiasm and initial success, they often become confused and uncertain as they progress. Whether working on a class research project or simply using the library, she speculates that a substantial number of people give up after their initial search for information. According to Kuhlthau, "this dip in confidence seems to be a natural stage in the ISP. This Uncertainty Principle is expanded by six corollaries: process, formulation, redundancy, mood, prediction, and interest.

View a chart showing the connection between the stages of the information search process and student feelings, thoughts, and actions.

Kuhlthau finds that students go through a number of different feelings as they proceed through the stages including uncertainty, optimism, confusion, frustration, doubt, clarity, sense of direction, confidence, relief, and satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Their thoughts go from ambiguity to specificity and their interest increases. Their actions move from seeking relevant information to seeking pertinent information.

Zone of Intervention

Uncertainty is related to unclear thoughts about a topic or question. Teachers need to be aware of this uncertainty and be prepared to help students deal with their frustrations. The zone of intervention is the time when a user needs help to move ahead. Librarians need to identify this "teachable moment" and be prepared with learning materials to provide assistance. No matter how much experience students have with the process, they still experience uncertainty when faced with a new problem or task.

According to Kuhlthau "Intervention based on an uncertainty principle encompasses the holistic experience of using information from the perspective of the individual student."

She identified five zones of intervention with levels of mediation including organizer, locator, identified, advisor, and counselor. The levels indicate a need for a particular type of scaffolding to facilitate student work.

Process intervention strategies include collaborating, continuing, conversing, charting, and composing.

Read!

Read!

Read Students and the Information Search Process: Zones of Intervention for Librarians by C.C. Kuhlthau (Advanced in Librarianship, Vol. 18, 1994).

Information Search Process in the Digital Age

Carol Kuhlthau's work transfers well into the digital age. By combining a constructivist approach to information age learning, she's expanded her thinking to include strategies for coaching students in the ISP in the following areas of collaborating, continuing, conversing, charting, and composing. According to Kuhlthau the constructive process of learning involves: acting and reflecting; feeling and formulated; predicting and choosing; interpreting and creating.

Read Information Search Process by C.C. Kuhlthau from Rutgers University.

Read Information Search Process by C.C. Kuhlthau from Rutgers University.

Read Learning in Digital Libraries: An Information Search Process Approach by Carol Collier Kuhlthau (Library Trends, Spring 1997, Vol 45, Issue 4, p708, 17p.) (IUPUI password required)

Information Skills Model by Irving

In 1985, Ann Irving discussed this idea of cross-curriculum connections in a book titled Study and Information Skills Across the Curriculum. She stated that the research process is an integral part of our everyday lives and it's directly linked to life-long learning. When we're sick, we seek medical information. When we're buying a product we look for a good buy.

Irving stressed a resource-based learning approach that emphasized addressing individual differences in teaching and learning style. She also emphasized the importance of students, teachers, and librarians collaborating toward this joint goal.

Although many other models came after Ann Irving, her Nine Step Information Skills Model continues to be used in schools. The steps include:

- Formulating

- Identifying

- Tracing

- Examining

- Using

- Recording

- Interpreting

- Shaping

- Evaluating

Information Seeking

Genealogy investigations are an excellent example of the need for information skills in everyday life. Many public libraries offer workshops to assist genealogists and family historians in their quest for information.

Skim Seeking Information, Seeking Connections, Seeking Meaning: Genealogists and Family Historians by Elizabeth Yakel. Notice the focus on adult learners.

I-SEARCH by Macrorie

I-Search is "an approach to research that uses the power of student interests, builds a personal understanding of the research process, and encourages stronger student writing" (Joyce & Tallman, vii). The key element of this approach is that students select topics of personal interest. This model also stresses metacognitive thinking. Students are asked to keep a log of their action, thoughts, and feelings as they move through the process. In addition, students are asked to reflect on their previous research experiences to set the stage for an appreciation of the research process.

Based on Ken Macrorie's 1988 book entitled, The I-Search Paper, I-Search proposes an alternative to the traditional research paper. Often used by middle and high school students, the inquiry-based approach can also be used with elementary or college students. According to Ken Macrorie, the key to I-Search is that students work on meaningful projects.

In the 1990's Marilyn Joyce and Julie Tallman adapted Macrorie's approach for use in the research process.

I-Search is a process that includes four general steps:

- Selecting a topic - exploring interests, discussing ideas, browsing resources

- Finding information - generating questions, exploring resources

- Using information - taking notes, analyzing materials

- Developing a final product - developing communications, sharing experiences

Pathways to Knowledge by Pappas and Tepe

The Pathways to Knowledge model sponsored by Follett was developed by Marjorie L. Pappas and Ann E. Tepe. Designed for children and young adults, the authors stress the importance of questioning and authentic learning. Their focus is on a nonlinear process for finding, using, and evaluating information.

In their book Pathways to Knowledge and Inquiry Learning (2002), Pappas and Tepe drew on the example of a fourth grade class in Kentucky that was concerned about the removal of a mountain top by a coal company. Working collaboratively, the classroom teacher and school library media specialist designed a learning experience to explore the issue. The project ultimately involved the students in testifying at legislative hearings and holding allies to promote public awareness of the issue. The children won the President's Environmental Youth Award for their project.

This nonlinear model was originally designed as a diagram rather than a series of steps. Students are encouraged to continuously explore and reassess as they process information.

The model includes the following stages:

Appreciation and Enjoyment

Examine the world.

"Individuals appreciate literature, the arts, nature and information in the world around them through varied and multiple formats, including stories, film, paintings, natural settings, music, books, periodicals, the Web, video, etc. Appreciation often fosters curiosity and imagination, which can be a prelude to a discovery phase in an information seeking activity. As learners proceed through the states of information seeking their appreciation grows and matures" (Pappas & Tepe, 2002, p.4)Presearch

Develop an overview; explore relationships

"The Presearch stage enables searchers to make a connection between their topic and prior knowledge. They may begin by brainstorming a web or questions that focus on what they know about their topic and what they want to know. This process may require them to engage in exploratory searching through general sources to develop a broad overview of their topic and explore the relationships among subtopics. Presearch provides searchers with strategies to narrow their focus and develop specific questions or define information needs." (Pappas & Tepe, 2002, p.6)Search

Identify information providers; select information resources; seek relevant information

"During the Search stage, searchers identify appropriate information providers, resources and tools, then plan and implement a search strategy to find information relevant to their research question or information need. Searchers are open to using print and electronic tools and resources, cooperative searching and interacting with experts." (Pappas & Tepe, 2002, p.8)Interpretation

Interpret information

"Information requires interpretation to become knowledge. The Interpretation stage engages searchers in the process of analyzing, synthesizing and evaluating information to determine its relevancy and usefulness to their research question or information need. Throughout this stage searchers reflect on the information they have gathered and construct personal meaning." (Pappas & Tepe, 2002, p.16)Communication

Apply information; share new knowledge

"The Communication stage allows searchers to organize, apply, and present new knowledge relevant to their research questions or information need. They choose a format that appropriately reflects the new knowledge they need to convey, then plan and create their product." (Pappas & Tepe, 2002, p.19)Evaluation

Evaluate process and product

"Evaluation (self and peer) is ongoing in their nonlinear information process model and should occur throughout each stage. Searchers use their evaluation of the process to make revisions that enable them to develop their own unique information seeking process. It is through this continuous evaluation and revision process that searchers develop the ability to become independent searchers. Searchers also evaluate their product or the results of their communication of new knowledge." (Pappas & Tepe, 2002, p. 21)

Pre-Search by Rankins

Virginia Rankin's book titled The Thoughtful Researcher: Teaching the Research Process to Middle School Students (Libraries Unlimited, 1999) continues to be popular with school library media specialists.

Virginia Rankin is best known for her approach to the Pre-search Process focusing on building a solid foundation prior to materials exploration. Rankin identified a number of effective pre-search strategies such as:

- KWL

- Brainstorm, Read, Categorize

- Relax, Read, Reflect

- Newspapers for a Background

- Journal Writing

Developing quality questions can be difficult for students. Rankin (1999, p. 31) recommends the following criteria for evaluating research questions:

- based on knowledge of the topic

- focus not too broad or too narrow

- interesting to researcher

- potentially interesting to others

- feasible resources available to answer questions

Rankin has also identified a series of steps in the research process:

- Step 1 - Presearch

- Step 2 - Plan the search

- Step 3 - Search for information

- Step 4 - Select information

- Step 5 - Interpret and record information

- Step 6 - Evaluate information

- Step 7 - Communicate the information

- Step 8 - Evaluate the process

Rankin (1992) stresses the importance of student assessment. Below is her criteria for judging student's pre-searches.

- Information from four different sources, with a bulk of the information not from a single source

- Four bibliography cards

- Note cards keyed to all four sources

- Notes help answer researcher's questions (no irrelevant information)

- Adequate information for all three questions

- Notes summarized

- Notes in own words

- One idea per note card

- Sufficient quantity (15-50 note cards)

- No glaring inaccuracies; double-check facts, especially numbers

Read!

Read!

Read Pre-search by Virginia Rankin in School Library Journal (March 1992, 38(3), 168).

Consider the importance of a learner-centered approach to the inquiry process.

View Student-Generated Topics (0:30).

View Student-Generated Topics (0:30).

Virginia Rankin discusses the importance of student-generated topics and questions. - Excerpt from “The Pre-search”

Use of this video clip complies with the TEACH act and US copyright law. You should be a registered student to view the video.

REACTS by Stripling and Pitts

The late 1980s was a time when many librarians and educators were discussing the importance of information skills. Barbara Stripling and Judy Pitts focused their attention on the need for high level thinking in the research process. It became known as the Stripling and Pitts Research Process Model or REACTS.

The REACTS Taxonomy developed by Barbara Stripling and Judy Pitts focuses on critical thinking in the research process. This model focuses on strategies for ensuring high level thinking and resulting quality products. If students research at a low level, they're likely to react at a low level. In other words, if students spend their time collecting facts, they'll probably create a low-level recall-type report. However if they spend their time in the research process integrating, concluding, and conceptualizing, then their final product will be reflect transformation and synthesis of information.

The REACTS Taxonomy includes the following elements:

- Recalling

- Explaining

- Analyzing

- Challenging

- Transforming

- Synthesizing

Research Assistant by Bevilacqua

In the early 1990s, Ann Bevilacqua developed the first computer-based instruction to assist with the research process. The software tool helped guide students through the process of conducting research.

The ten steps in her process included:

- Understand assignment

- Select topic

- General reading on topic

- Formulate thesis

- Conduct library research

- Make an outline

- Write a first draft

- Get supporting materials for argument

- Review and revise

- Final form

Research Cycle by McKenzie

The Research Cycle by Jamie McKenzie was first developed in 1995 to meet the needs of students working on essential questions for school research. The model places emphasis on questioning and rejects many of the model that focus on topical research. His model requires students to make decisions, create answers, and show independent judgment. Another feature of this model is its focus on actively revising and rethinking the research questions throughout the process. With an emphasis on problem-solving and decision-making, the model encourages a recursive approach rather than a linear approach.

McKenzie (2000) stresses the importance of students as information producers rather than simply information gatherers. Students move repeatedly through the following steps in the research cycle:

- Questioning

- Planning

- Gathering

- Sorting & Sifting

- Synthesizing

- Evaluating

- Reporting * (after several repetitions of the cycle)

Read!

Read!

Read Research Cycle 2000 by Jamie McKenzie at FromNowOn to learn more about this model that involves questioning, planning, gathering, sorting & sifting, synthesizing, evaluating, and reporting as part of a cycle.

Research Process Model by Stripling and Pitts

The Research Process by Stripling and Pitts was developed to guide research assignments in the K-12 environment. Their emphasis on thinking and reflecting is intended to encourage deep thinking.

The ten step process includes:

- choose a broad topic

- get an overview of the topic

- narrow the topic

- develop a thesis or statement of purpose

- formulate questions to guide research

- plan for research and production

- find, analyze and evaluate sources

- evaluate evidence, take notes and compile a bibliography

- establish conclusions and organize information into an outline

- and create and present a final product

Research Process Helper (4-Step Research Model) by Hughes

A four-step research process is provided for elementary students in a gifted and talented classroom and for middle school students. Students work on the preparation steps, which include using a task definition chart and webbing tools, and accessing information where generic and school-specific information is found. Next, the process provides excellent ideas on processing information and the final step of transferring the information to others. This thoughtfully developed site can serve as a model for many activities crafted jointly between the teacher-librarian and the content-area teacher.

The Research Helper involves on a four step research process:

- Preparing

- Accessing

- Processing

- Transferring

To see the process, visit the Research Helper website.

Scientific Method

The basic definition of the Scientific Method includes these steps:

- observation and description of a phenomenon

- formulation of a hypothesis to explain the phenomena

- use of the hypothesis to predict existence of other phenomena

- performance of experimental tests of the prediction and inferring a conclusion

- some include a fifth step of presenting, debating and/or application of findings

The inquiry process gives heavy emphasis to development of questions at each step.

- What questions come from observation?

- What questions are relevant to the hypothesis?

- What questions formulate the prediction?

- What questions are answered from the test of the prediction and what questions, new and old, remain unanswered in part or in full?

The process of Information Inquiry involves application of the ancient Socratic Method of teaching through self-posed and mentor-posed questions in order to gain meaning in today’s overwhelming Information Age. Further application of the Scientific Method gives a systematic structure to this process. It places students and teachers in the role of Information Scientists. This analogy will be explored as one that may open new paths for students and teachers to investigate not only phenomenon identified from typical subjects of study, but to also test and predict the value, relevance and meaning of information itself. As “information scientists” should the learner be expected to journal, debate, compare, and present his or her observations on the value of the information encountered and the need for information that may not be available or possible to obtain?

After visiting an area farm, students became fascinated with how farmers grow and sell their crops. How do they decide what to grow? Why do they rotate crops? When do they plant? How do they decide when to sell? What factors impact the price of crops?

After visiting an area farm, students became fascinated with how farmers grow and sell their crops. How do they decide what to grow? Why do they rotate crops? When do they plant? How do they decide when to sell? What factors impact the price of crops?

One student information scientist traced the Chicago Board of Trade corn prices over a week and graphed the results. See the graphics below: one in marker and the other computer-generated.

Explore the steps of the scientific method:

- Observe - Watching carefully, taking notes, comparing and contrasting

- Question - Asking questions about observations, asking questions that lead to manageable investigations, evaluating and prioritizing questions

- Hypothesize - Suggesting possible explanations consistent with available observations

- Predict - Suggest an event or result in the future based on analysis of observations

- Communicate - Informing others through means of communications relevant to the conclusions and the audience addressed

Super 3™ by Eisenberg and Berkowitz

Although The Big 6 only includes six steps, some primary teachers find it overwhelming for their young learners. As a result, teachers have developed modified versions to meet their needs. Eisenberg and Berkowitz have developed a version called the Super 3 for very young children. It includes three steps:

- Plan

- Do

- Review

Explore the Super 3 page. Compare this approach to the Big6 model.

WebQuest

WebQuests provide an authentic, technology-rich environment for problem solving, information processing, and collaboration. This inquiry-based approach to learning involves students in a wide range of activities that make good use of Internet-based resources.

Bernie Dodge developed the WebQuest concept back in the mid 1990s. His resources can be found at WebQuest.org.

Dodge’s model is similar to other information inquiry models. Critical attributes of a WebQuest include:

- an introduction that sets the stage of the activity

- a doable, interesting task

- a set of information resources

- a clear process

- guidance and organizational frameworks

- a conclusion that provides reflection and closure.

Try It!

Try It!

Complete WebQuests, the free, online workshop from Educational Broadcasting Corporation.

Skim Internet Expeditions: Exploring, Using, Adapting, and Creating WebQuests by Annette Lamb to learn more about this approach.

Topics in Information Inquiry

The librarian plays an important role in working with faculty to design effective activities that help students acquire and apply subject area knowledge as well as essential inquiry skills.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to Digital Detectives: Fluid Environments for Inquiry. Although designed for K-12, this resources is useful for all ages of inquirers.

Work your way through this workshops viewing the videos and skimming the materials. You'll find lots of useful resources.

This words and images above represent just a few of the key topics associated with information literacy. Explore the course website for information about each topic.

Let's explore as series of topics that are often part of the information literacy curriculum:

Analysis

Analysis emphasizes the breakdown of the materials into its constituents or related parts and of the way those part may be organized and relevant to each other. Analysis also may be directed at the techniques and devices used to convey the meaning or to establish the conclusion of a communication.

Identifying similarities and differences is an example of breaking down ideas and finding common underlying structures.

Callison (2006, 275) states that students "use analysis skills to critically review a document written by someone else or a task presented to the student to determine the merits of the elements or options." Student determine the meaning of arguments and the quality of their construction. He states that activities that require analysis include:

- distinguish fact from hypothesis in a communication

- identify conclusions and supporting statements

- distinguish relevant form extraneous material

- note how one idea relates to another

- see what unstated assumptions are involved in what is said

- distinguish dominant from subordinate ideas or themes

When students analyze documents for informational elements, Callison (2006, 276) notes that they must look at authority, source, context, and method. When students analyze documents for relationships, they must distinguish fact from opinion, relevant from irrelevant, and causal relationships.

Audience Analysis

Audience analysis involves the processes of gathering and interpreting information about the recipients of oral, written, or visual communication. Audience awareness involve the conceptions of the writer, speaker, or performer concerning the recipients of his or her communication. Regardless of whether the author is sharing an oral history, debating an issue, or writing an editorial, the writer or speaker must be aware of the needs, interests, and expectations of his or her audience.

Callison and Lamb (2006) suggest that students need to learn how to analyze their audience and design communications to fit the needs of their audience. Students might be asked to communicate with learners from another culture or write a letter to a government official.

Authority

Information scientists use authority when judging information.

Bias

Bias is a prejudice generally associated with preference for a particular point of view or perspective. Novice researchers need opportunities to consider a wide spectrum of resources in order to gain experiences identifying bias. It is possible to find some level of bias in all forms of communication.

When judging information, bias is one of the most challenging criteria. While eliminating bias is often viewed as an important skill, understanding the reasons for and implications of bias is equally important. Bias determines the information selected and valued, so it understanding its nature is critical to becoming information fluent.

Callison (2006) noted many terms associated with bias including:

- Selective Thinking

- Communal Reinforcement

- Ad Hoc Hypothesis

- Wishing Thinking

- Stereotype

- Hidden Bias

- Propaganda

- Conventional Wisdom

- Group-Think

Rozakis (2004) identified three forms of bias:

- Bogus claim. A claim can be considered false when the speaker or writer promises more than he or she can deliver

- Loaded term. A term is loaded when it carried more emotional impact than its context can really support.

- Misrepresentation of fact. Such may involve wrong data, false data, and over-simplification of fact.

Carroll (2003) identified "confirmation bias" as a type of selective thinking where one confirms ones own beliefs and ignoring other perspectives.

According to Callison (2006), students need to be able to detect bias in the media. He suggests looking for the following elements:

- Temporal bias - bias toward immediate, new events, and popular figures

- Bad News bias - bias toward the negative

- Visual bias - bias toward only showing quick visual depictions

- Narrative bias - bias toward creating conflict when there is none

- Balance bias - bias toward a balanced view or giving equal time

Fitzgerald (1999) suggests that students need to overcome "belief perseverance" that she described as "a person's refusal or inability to relinquish a belief despite new information discrediting it."

Concept Maps

Concept mapping is a heuristic device that has proven to be useful in helping learners to visualize the relationships or connections between and among ideas. Of equal usefulness, mapping of term relationships helps to demonstrate to the teacher what the learner is constructing or assimilating. Thus, while mapping is a method to organize the pieces taken from a new piece of information (article, chapter, lecture, etc.), it presents a visual for the learner and teacher to further discuss the merits of what the learner believes to be the new knowledge gained.

Authentic problems are ill-structured, require students to address conflicting information, and may conclude with many possible solutions. Students must learn to gather and evaluate evidence from many sources and weight possible conclusions. Concept maps work well to help students organize and analyze their resources and thinking. An interesting way to introduce this type of activity is in the form of a mystery. Why is the eagle on the Great Seal of the United States? What words are on the Great Seal and how were they chosen? The students began with two “comfort sources”: the print encyclopedia and the Enchanted Learning website. These sources were easy-to-read and provided background information about the Great Seal. As a class, students identified the features of the Great Seal and the many places it is found in U.S. government materials. Each child selected a mystery they wanted to investigate associated with the seal. Students were asked to pay careful attention to the different perspectives represented by websites providing information about this mystery.

The example shown above (Click to enlarge the image) addresses the question of why the eagle in the Great Seal is depicted holding arrows. A concept map was used to organize findings using various website resources found when using their favorite search engine, Google. Two categories were identified: those who felt the arrows meant war and those that thought they depicted unity. Inspiration was used to create the concept map. This software allows students to make hyperlinks to the resources used in their project. They can also take notes and incorporate graphics. In this case, the student used three icons to identify those website resources they felt exhibited clear bias, were from well-known authoritative sources, or were unable to evaluate for quality. The students found conflicting information and were successful in organizing and evaluating the quality of information. As they added each idea, they were able to gain a better understanding of the events and ideas that lead to the choice of the bundle of arrows. The concept map served as a tool for sharing their findings with their peers. In addition, it provided a quick way to cite and access the website resources used in the project.

Although flipchart paper and markers can be very effective for producing and displaying concept maps, technology tools such as Inspiration and Kidspiration have enhanced the tools available for the production of concept maps. These tools allow creators to easily manipulate, revise, and expand maps without worried about penmanship or erasing. In addition, hyperlinks, photographs, audio, and video can easily be added to address learning styles and facilitate differentiation. Templates and lesson plan ideas are available to assist teachers as they plan for the use of concept maps in learning.

Callison (2006, 330) described the advantages of concept mapping during inquiry:

- Helps to define the central idea and give it perspective.

- Helps visualize relationships and subset.

- Key or essential concepts emerge and become trigger words or phrases that are remembered, and later will serve to help the learner recall the minor or detailed points that emerge from these major ones

- Gaps will become apparent, which will lead to new questions that will guide what to read net or lead to new questions.

Evaluation

Students need to be able to evaluate information.

Taylor (2012) studied the information seeking activities of member of the millennial generation. He found that individuals born between 1982 and 2000 have information searching skills, but resist the use of objective information evaluation standards when filtering information.

Gross and Latham (2011) found that information quality was not a concern among college students. In addition, most were unaware of objective measures for evaluating information.

In Source evaluation and information literacy: findings from a study on science websites, Bird, McInerney, and Mohr (2010, 185) studied users' judgments about web sources. They found that instruction "should emphasize understanding authorship cues, purpose of a site, and currency."

Go to the Deconstruction Gallery at the Media Literacy Project. Then, go to FactCheck.org from Annenberg. Both of these sites asks viewers to critically evaluate information.

Evidence

Although young people aren't expected to be lawyers, they should be able to identify, organize, and cite evidence. Evidence is information that can be used to demonstrate the truth of an assertion. Student investigators can test information and seek verification, second opinions, and validation of content by checking credentials, publishers and impressions from his peers (fellow students) and mentors (instructional media specialists).

According to Callison (2006, 369), students need to be able to "test information by seeking verification, second opinions, and validation of content by checking credentials, publishers and impressions from his peers (fellow students) and mentors (instructional media specialists)."

Callison (2006, 373-375) identified the "Capital Cs to Challenge Evidence":

- Common

- Conventional Wisdom

- Circumstantial

- Cherry Picked

- Comforts

- Chains or Connects

- Counters, Convincing, and Changes

- Credible

- Critical or Counts Highly

- Creative

- Controversial

- Copy, but give Credit

- Classic

- Convey and Communicates

- Council and Confidence

- Continues

Barbara Stripling has written one of the most comprehensive and convincing essays on the relationships among inquiry-based learning, information literacy and k-12 curriculum. Among a rich list of curricular ties, she offers these examples that illustrate how teaching inquiry involves applications at different grade levels with the instructional media specialists working collaboratively to facilitate a progressive scaffolding of investigative experiences from elementary to secondary school (2003, page 26).

"Evaluation of sources is critical to inquiry in social studies because of the interpretative nature of the discipline. Students should assess the value of a source before they even look at the specific information within the source. If teachers and librarians have selected the source, then they should share their thinking process with students. The criteria that need to be emphasized (at age-appropriate times) are authoritativeness of the author/publisher; comprehensiveness of the information (students are seeking in-depth information, not collections of superficial facts); organization and clarity of the text (students need to be able to find and comprehend relevant information without getting lost in extraneous links or subtopics); and quality of the references (the sources of the cited evidence) [and further understand our quality citations can lead to additional relevant evidence]. Obviously, in the age of the Internet, responsibility for evaluation of sources has largely shifted from librarians to students. Careful instruction and guidance must accompany that shift.

Evaluation of specific information and evidence is also a key thinking strategy for inquiry in social studies. Librarians and classroom teachers probably want to emphasize discernment of fact versus opinion and help students understand how each can be used effectively. Students, particularly as the secondary level, must learn how to identify point of view and recognize its effect on the evidence. Their responsibility is to find enough evidence from different points of view that they [may consider] … a balanced perspective. Sources that present opposing viewpoints are helpful to provide that [attempted] balance of evidence. Secondary students must also be taught to detect degrees of bias (from slightly slanted point of view to heavily slanted propaganda)."

- Factcheck.org - explore evidence related to topics in the news and current issues.

- Trusttheevidence.net - explores the truth behind the research findings that affect everyday healthcare

Figurative Language

Figurative language can bring any topic alive for students. It provides the reader or listener with a mental image of an idea or comparison. For this reason, it's one of the most popular teaching and motivation tools. For example, a science teacher might demonstrate how the heart is like a pump. A librarian might compare looking for information on the Internet to searching for a needle in a haystack.

Analogies, metaphors, and similes are three types of figurative language that can easily be integrated into the learning environment. Other examples include alliteration, cliche, hyperbole, image, or personification,

Analogy. An analogy involves comparing two things that contain some similarities, then broadening the comparison through logical inference.

Teachers often use analogies to assist students in inquiry-based learning activities. For example, an analogy may provide inspiration for an investigation or a context for learning. Students may be asked how a cell is like their school or photosynthesis is like making pizza.

According to Callison (p. 101), "an instructional analogy is an explicit, nonliteral comparison between two objects, or sets of objects, that describes their structural, functional, and causal similarities".

Explore Private Eye. This project explores the use of analogy, changing scale, and theorizing in learning.

Metaphor. A metaphor is comparing two things by using a word or phrase in a way that it's not normally used to visualize an idea.

Simile. A simile is a figure of speech that makes a comparison between two unlike things using the words like or as.

Explore 42eXplore: Figurative Language to explore additional terms, definitions, examples, and resources.

Hypothesis Testing

The ability to ask questions and generate hypotheses is an important information skills.

Idea Strategies

Ideas help us to move forward, to explore, and to frame questions that are meaningful to us and hopefully to others. Idea strategies are methods that help the learner both comprehend and communicate their thoughts.

In Idea Strategies, Callison (2006) states that maturing information students need help with the complexities of the communication process. He recommends providing students with help in getting started, framing questions, processing information, and writing communications.

Berke and Woodland (1996) suggest thought started to ask the right questions. A few examples are shown below:

- Definition - What does X mean?

- Description - What are the different features of X?

- Simple Analysis - What are the component parts of X?

- Process Analysis - How is X made or done?

Harvey and Goudvis (2000) suggest strategies for helping students extract ideas from text:

- Text-to-Self - How is the text connected to your life?

- Text-to-Text - How is the information connected to previous things you've read or watched?

- Text-to-World - How is the text connected to the outside world including events, people, or issues?

The Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL) weaves idea strategies throughout its tutorials to help students in everything from identifying topics to processing information and developing communications.

Information Search Strategies

Information search strategies are a systemic way to accomplish the task of finding information and includes defining the information need, determining the form in which it is needed, if it exists, where it is located, how it is organized, and how it retrieve it.

According to Callison (2006, 401-402), information search strategies have evolved over the past thirty years from orientation to sources and services to awareness of key literature to a focus on critical thinking and problem-solving to an emphasis on inquiry as a process.

Search tactics are an important way for students to refine their search. Callison (2006, 403-404) stresses that the student "must gain an understanding of not only how to employ the tactics, but when and why to apply them." Examples include:

- Bubble - look for a bibliography already prepared; to see if the search work one plans has already been done in a usable form by someone else; to examine the bibliography of a valued source and select key reference leads.

- Record - keep track of trails on has followed and of desirable trails not followed up on or not completed.

- Brainstorming - getting ideas and considering alternative ideas to enrich understanding

- Consulting - testing ideas with others

- Rescuing - be persistent and thorough in order to prevent premature conclusions

- Wandering - browsing in a variety of resources to inspire the imagination and ignite thinking

- Breaching - considering a different subject area or domain

- Reframing - reexamining the question to get rid of distortions or erroneous assumptions

- Jolting - changing the point of view by looking at the question as it has been addressed by different groups

- Focusing - narrowing the search or the concept

- Dilating - expanding the search to widen the focus

- Neighboring - cluster terms to be located within the text

- Reflection - stopping at several points in order to determine what else might come to mind

- Parallel - to make the search formulation broad or broader by including synonyms or otherwise conceptually parallel terms

- Contrary - to search for a term logically opposite from the describing the desired information

- Tracing - using the subject tracings that tag relevant citation hits during searching

- Linkages - from the best sources locate and read, identify what may be especially valuable

Interview

The interview is a valuable tool used in the inquiry process to gain primary information that will help clarify and add meaning.

According to Callison (2006, 407-410), the mature information literate student will use the personal interview to verify evidence from written sources, add color and story, and extend a line of inquiry. Callison suggests the following approaches for oral history interviews:

- Information interviewee in advance

- Gain permission

- Learn to use the equipment prior to the interview

- Use quality recording medium

- Do a pre-interview

- Be on time

- Record the name, date, and location

- Keep the interview to 30 minutes

- Stay away from noisy areas

- Use personal photographs to jog memories

- Keep questions short and let the interviewee tell the story

- Edit the interviews

- Check the name and address of the interviewee

- Send a thank you

- Design an event to highlight the project

Read!

Read!

Read Developing interview skills and visual literacy: a new model of engagement for academic libraries by Kayo Denda (April 2015).

How could the ideas in the article be applied to other information literacy skills?

Note-taking

Taking notes is an important activity through inquiry. Note-taking is the process of writing pieces of information that can later be reviewed. However it's much more than learning to make outlines or properly record information. A large part of note-taking is the selecting of essential information.

The introduction of Post-it notes has provided note-takers with an easy way to organize, then rearrange their notes.

Callison (2006) suggests a number of principles for selection of information and transfer to notes:

- Be very selective of information for capture.

- Be certain to capture and transfer the URL if using the web.

- Capture information from the document that shows how authoritative, bias and/or current the information is.

- Create subtopics for topic organization and paraphrase key ideas and terms

- Markup pages using printouts or one of the the many online note tools.

- Follow copyright guidelines

- Paraphrase so information is ready to use and doesn't plagiarize.

- Note full bibliographic information.

According to Callison (2006) as the notetaker's quest becomes more focused, the inquirer begins to locate specific pieces of information such as:

- data from text, charts, and tables which are relevant to the situation and may help prove a point

- data which are relevant to the situation and may help disprove or counter a point, proposal, or plan.

- key facts, especially not commonly known

- key names associated with issues, events, happenings and their role

- key terms and definitions, especially if not know prior to this research effort

- opinions and observations of experts; any of these first three can be the basis for information becoming evidence

- events or happenings which illustrate, give context, provide an example case relevant to the topic

- a chain of sources which give support to the need to show similar evidence from more than one or two sources; pieces which substantiate previous information

- an item which fills in a gap may be unique data or a difference observation then found anyplace else

- information which is either more current than previous information, or provides historical context for chronological comparison of information

- above all, the information item is relevant, authoritative, and understandable and will help clarify issues, events and appending that must be described in final report or presentation

To learn more, go to The Digital Dog Ate My Notes: Tools and Strategies for 21st Century Research by Annette Lamb.

Oral History

Oral history is an account conveyed by word of mouth. An oral history project may involve recording and sharing recollections of events in a person's life and how those activities impacted themselves and others. These interviews may be transcribed and shared in a written, audio, or video format.

Organizers

Organizers are tools or techniques that provide identification and classification along with possible relationships or connections among ideas, concepts, and issues.

From listing prior knowledge to classifying ideas, organizers can be used throughout the inquiry process.

Plagiarism

Plagiarism involves claiming another author's work as your own. Although plagiarism can occur unintentionally when a writer forgets to include quotation marks or a citation, it is most often viewed as academic dishonesty.

According to Callison (2006, 470), a mature student information scientist knows that giving credit is not only the right thing to do, but also strengthens a communication.

Primary Resources

Primary sources are original objects or records that have survived the past. Some times referred to as "raw history," they represent a direct personal experience of a specific time in the past. Primary sources are artifacts such as official documents (birth certificates, marriage licenses, and property contracts), journals (diaries and letters), clothing, toys, tools, visuals (sketches, painting, and photographs), and more.

Barbara Stripling has written one of the most comprehensive and convincing essays on the relationships among inquiry-based learning, information literacy and k-12 curriculum. She states that "Use of primary sources is an important component of inquiry in social studies. Students must be taught to observe and draw valid interpretations from artifacts, ephemera, images, maps, and personal accounts. Student must be taught to interpret the primary sources in light of its context (e.g., a soldier writing a letter about a recent skirmish may think it the bloodiest battle of the war because he was injured; a photographer shooting a peace march from a low angle may convey a huge crowd, while an overhead shot might show a small crowd with empty streets behind it). Because so many sources are being digitized, students have more access to primary sources than they have ever had before [and the amount available online will grow tremendously over the coming years]. Primary sources may be particularly exciting to elementary students who have limited background knowledge. They, therefore, need scaffolding to foster the validity of their interpretations" (2003, page 26).

Frances Jacobson Harris has demonstrated how challenging it is to manage visual and artifact interpretation skills of middle grade students.

To learn more, read Awakening and building upon prior knowledge by Kristin Fontichiaro.

To learn more, explore the Teacher Resources from the Library of Congress.

Explore escrapbooking.com to learn more about using primary sources in classrooms and libraries.

Story

Teachers and students love stories. They can bring dry content alive! Allegories and fables use characters or events to represent ideas or principles in a story.

Explore DigiTales: The Art of Telling Digital Stores.

A story that uses fictional characters, problems, and ideas to illustrate a factual situation is called an allegory.

Go to Bhutan, the Last Shangri-La: Buddhism and Ecology. Lesson with allegory.

Synthesis

Synthesis is the fusion of separate elements or substances to form a coherent whole. In research, synthesis is the combination of thesis and antithesis in the dialectical process, producing a new and higher form of being (Callison, 2006).

Synthesis is not just the act of summarizing, paraphrasing or abstracting information from a document.

Synthesis should also include extracting inferences that link selected findings together in a logical and meaningful pattern. Questions might include (Callison, 2006),

- Based on opinions voiced by members of the group, what should be the steps to be taken next?

- Based on the analysis of your observations, what do you predict will happen next?

- Given the basic background necessary and an understanding of the relationship among characters, how would you rewrite this act?

Questioning

An essential information age skill, questioning can turn a boring assignment into an exciting project.

Jamie McKenzie has identified and created many helpful resources for stimulating student thinking and questioning.

Explore Questioning.org. Explore his resources and articles for ideas on incorporating questioning into your projects. Look for strategies on questions and questioning.

Whether answering simple reference questions or helping students with complex research projects, questioning is an important tool for the library media specialist.

The poster on the right comes from an elementary classroom. It reminds students to always ask questions.

To learn more, read Developing Questions and a Sense of Wonder by Kristin Fontichiaro in School Library Monthly (October 2010).

Read!

Read!

Read Troublesome concepts and information literacy: investigating threshold concepts for IL instruction by Amy Hofer, Lori Townsend & Korey Brunetti.

What do you see are "troublesome" concepts?

Try It!

Try It!

Select one of the information literacy topics discussed. Investigate the instructional needs related to this topic. Are there standards connected to this topic? Write an instructional goal that would address a specific instructional need.

Instructional Analysis

After identifying your instructional goal and your information skill content focus, you're ready to begin the process of instructional analysis. Instructional analysis is used to identify the skills learners need to achieve the stated instructional goal. Ideally, this analysis would include everything needed to achieve the goal without omission, but also without superfluous skills.

After identifying your instructional goal and your information skill content focus, you're ready to begin the process of instructional analysis. Instructional analysis is used to identify the skills learners need to achieve the stated instructional goal. Ideally, this analysis would include everything needed to achieve the goal without omission, but also without superfluous skills.

Instruction analysis involves identifying relevant subordinate skills or steps in a procedure that are required for a student to achieve the goal. A subordinate skills is a skill that, while perhaps not important in and of itself as learning outcome, must be acquired in order to learn "subordinate" skills. Remember the old adage, you must be able to walk before you run. Or, you must be able to identify "straight flushes" and "full houses" before you can apply the rule that a "straight flush beats a full house."

Types of Learning

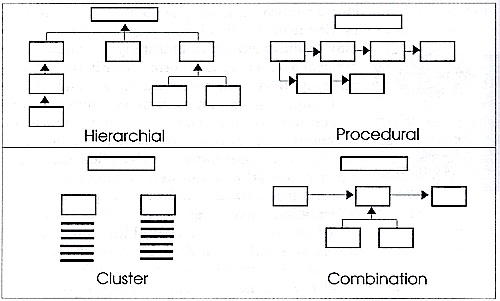

The instructional analysis approach you use is directly related to the type of learning represented by the instructional goal. For example, a procedural analysis is normally used with psychomotor skills and a hierarchical analysis is often used with intellectual skills.

The hierarchical approach to instructional analysis identifies all the skills relevant to the goal and their relationship. The instructional goal appears at the top and subordinate skills are arranged below the goal. These subordinate skills are connected by lines to show relationships between various skills. Instruction on skills is then sequenced from the bottom to the top. Verbal information and attitudinal skills are often attached horizontally. See the diagram above.

The procedural approach to instructional analysis is used for psychomotor goals. The purpose of a procedural approach is to identify the steps a person performs in accomplishing the goal. In addition, it clearly defines the sequence of these steps. Steps are arranged in sequential order below the goal and connected by lines. See the diagram above. Although the procedures are normally laid out left to right, you can create a diagram in a format that meets your needs. Explore the Downloading e-books example. Notice that it goes from the top to the bottom of the page.

The cluster approach to instructional analysis is used for verbal information goals. The cluster approach is used to identify all the information needed to achieve the goal. Information may be diagrammed as hierarchy or in an outline form. See the diagram above.

Complex goals that contain components from two or more learning domains require the use of a combination approach to instructional analysis. Steps in a procedure are identified and the subordinate skills of the steps are shown as hierarchies below the particular step. Verbal information supporting an intellectual skill is attached to it with a horizontal line connecting the vertical sides. See the diagram above.

Let's explore four examples show in the visual below.

Example 1: This instructional goal can be accomplished by learning to perform three steps (i.e., by learning three part-skills and an executive subroutine).

Example 2: This instructional goal has three subordinate skills. All three skills are independent of each other (i.e., no prerequisite relationship exists between them).

Example 3: This instructional goal has ten elements altogether. Upon initial analysis, the goal was determined to have two major groups of information. The first group was composed of three items of information and the second group had five.

Example 4: This instructional goal can be accomplished by learning to perform two steps. However in performing the first step, the learner actually does three separate actions in sequence. And, with respect to step two, it is a relatively rare individual who can perform that step without also being able to perform two intellectual skills that are independent of each other.

Conducting an instructional analysis requires a thorough understanding of your content. Before attempting to create an instructional analysis, it's a good idea to conduct a "content analysis." In other words, brainstorm to create a list of "key words related to the topic" or "major steps in the procedure." For intellectual skills consider the steps you go through in your mind for achieving the instructional goal. Write these steps as a procedure and then derive subordinate skills below each step.

Conducting an instructional analysis requires a thorough understanding of your content. Before attempting to create an instructional analysis, it's a good idea to conduct a "content analysis." In other words, brainstorm to create a list of "key words related to the topic" or "major steps in the procedure." For intellectual skills consider the steps you go through in your mind for achieving the instructional goal. Write these steps as a procedure and then derive subordinate skills below each step.

Along with collecting general content information, you also need to be collecting information that may be useful in developing our lessons. Examples, sample graphics, definitions, and quotations are just a few of the items you may wish to organize.

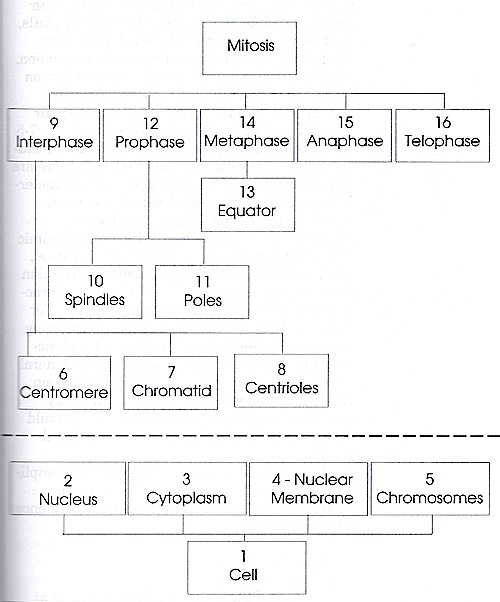

Let's examine at the topic of mitosis. Because the instructional goal for the mitosis example is an intellectual skill, the hierarchical approach will be used for the development of the instructional analysis. The student must be able to identify each of the five phases of mitosis independently. In addition, there are some scientific elements that the student must be able to identify before he or she can identify these phases. For example, the student must be able to identify a cell before he or she can identify parts of the cell. Examine the instructional analysis below.

Explore some examples of instructional analysis:

To learn more about instructional analysis, read The Systematic Design of Instruction by Dick, Carey, and Carey (2011).

Creating Diagrams

Many software packages (i.e., Inspiration, Microsoft SmartArt) and online tools can be used to create diagrams for instructional analysis. Exploratree provides wonderful templates to get started.

- Bubbl.us. Very easy to use. Try it without signing up. No distracting tools, choices, or options.

- Alternatives

- Cacoo. Create diagrams and concept maps.

- Creately. Create diagrams and mindmaps. Try it without signing up.

- DropMind. Create mindmaps. Must sign up.

- Gliffy. Works great, but very annoying signup reminders. Try it without signing up.

- Lovelycharts. Create charts. Must sign up.

- Lucidchart. Create a flowchart or concept map. Try it without signing up.

- Mindmeister. Create a concept map. Must signup.

- Mindomo. Create a mindmap. Must signup. Three maps for free.

- mind42. Create mindmaps with links. Must signup.

- Popplet. Create concept maps and post-its. Must signup.

- Slatebox. Create mindmaps. Must signup.

- Spicynodes. Includes lots of space for text, links, images, etc. Try it without signing up.

- SpiderScribe. Create maps and include notes, documents, images, etc.

View an example created in Bubbl.us for an instruction goal on scanning a photo using a printer.

Try It!

Use one of the online tools such as

Bubbl.us to create an instructional analysis for an instructional goal.

The previous section was originally published by Annette Lamb (1993) in Linkway Authoring Tool.

Resources

Abilock, Debbie. Building Blocks of Research at Noodle Tools. This document tries to show the relationships among information literacy, problem solving, curriculum design and teaching. Information literacy skills are examined in terms of Student Skills and Strategies, Student Outcomes, Curriculum and Teaching Design.

Berke, J. & Woodland, R. (1996). Twenty Questions for the Writer. Harcourt Brace.

Bird, Nora J., McInerney, Claire R., & Mohr, Stewart (2010). Source evaluation and information literacy: findings from a study on science websites. Communications in Information Literacy, 4(2).

Bowen, Carol (December 2001). A Process Approach: The I-Search with Grade 5: They Learn!. Teacher Librarian, 29(2), 14-18.