Standards, Needs and Goals

At the completion of this section, you should be able to:

- Trace the history of academic standards and information literacy standards.

- Compare and contrast national standards for information literacy including AASL, ISTE, and ACRL.

- Use the research results to identify instructional needs.

- Apply multiple approaches to gathering evidence to support instructional needs.

- Use collection maps and curriculum maps to identify instructional needs.

- Write instructional goals.

Begin by viewing the class presentation in Vimeo. Then, read each of the sections of this page.

Explore each of the following topics on this page:

Standards

Before jumping into the design of instruction, it's important to ask WHY? Why spend the time to create lessons, presentations, and handouts? Don't people just "know" how to use information? Of course, we know the answer is NO! Our professional standards establish guidelines for student expectations and our professional literature provides evidence of the need for instruction. Our job is to use these resources to establish a need and identify specific instructional goals that will address this need.

Academic standards are a set of clear, measurable outcomes that establish what students should be able to know and do. Standards have been established at all educational levels and subject areas.

Academic standards are a set of clear, measurable outcomes that establish what students should be able to know and do. Standards have been established at all educational levels and subject areas.

Although librarians have a primary interest in information standards, it's important to seek ways to reach out to faculty and collaborate on standards across the school and college curriculum. Many of the standards are shared across disciplines.

For example, students need to be able to evaluate the quality of information in every content area whether students are investigating issues related to global warming or causes of the American Civil War.

One of the problem facing librarians is the difference between how learners are taught to conduct research and how they actually do it in the real world.

Read!

Read!

Skim Information Literacy and Research Practices by

Nancy Fried Foster (2014).

Think about the implications of Foster's real-world findings.

Historical Perspectives

Educators through history have tried to identify the basic competencies of a "well-rounded" student. Although much of this knowledge, skills, and attitudes can be associated with particular content areas such as math, science, social studies, or language arts, other competencies seem to flow through all areas. For example, all students need to be able to access, process, and communicate information and ideas. Critical and creative thinking are important in all traditional curriculum areas.

Standards and guidelines for information literacy have evolved over the past century. As early as the 1920's the National Education Association and American Library Association were developing School Library Standards.

Standards and guidelines for information literacy have evolved over the past century. As early as the 1920's the National Education Association and American Library Association were developing School Library Standards.

During the 1970s and 1980s, a growing number of school librarians began to draw these skills together under an information literacy curriculum.

With the introduction of the computer in schools, a new wave of competencies emerged under the umbrella of computer literacy. However in recent years, educators have discovered that the core skills associated with the computer relate to information, communication, thinking, and learning rather than the hardware itself. Over the past decade, a new strand of competencies can be found in schools and organizations around the world. Although they have a range of names, they all relate to information, technology, and communication literacy in some way.

In the 1980s, the American Library Association and the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL) began defining information literacy and identifying competencies of information literate students. Recently, these standards have been revised.

Also in the 1980s, committees of American Association of School Librarians (AASL) and the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) came together to develop national standards for information literacy that are now in their second edition. Published in a document called Information Power, the revised edition (1998) included Information Literacy Standards for Student Learning as well as principles for school libraries and library media specialists.

Information Literacy Standards and K-12 Instruction Today

The key to integrating the standards into the school and college level curriculum is the matching of each information standard with content-area standards and examples. Librarians and faculty members must work together to support these connections.

The key to integrating the standards into the school and college level curriculum is the matching of each information standard with content-area standards and examples. Librarians and faculty members must work together to support these connections.

In some cases, the librarian must convince the subject matter educators that the information standards complement and support the content-area standards. They aren't "extras" or things that will take more time. The information literacy standards are essential in building lifelong learners in every content area.

Educators around the world have identified basic competencies in the information and communication area for both students and teachers. Some of these guidelines place emphasis on process, while others focus on the product. Technology plays a central role in some guidelines, while it is viewed as one of many options in other curriculum. In some cases, an integrated approach is taken. In other words, the scope and sequence for information and communication literacy has been merged with each content area.

Read!

Read!

Read Enduring Understandings - Where Are They in the Library's Curriculum? by Jean Donham in Teacher Librarian, 38(1), 2010.

What do you consider to be the "enduring understandings"?

Two sets of standards represent two perspectives: ALA/AASL (American Library Association) and AECT representing the "information perspective" and ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education) reflecting the "technology perspective."

In 2007, new standards were introduced by AASL (American Association of School Librarians). These standards known as the AASL Standards for the 21st-Century Learner have been adopted by individual states over the past several years.

The four learning standards state that learners use skills, resources, and tools to (AASL, 2007):

The four learning standards state that learners use skills, resources, and tools to (AASL, 2007):

- Inquire, think critically, and gain knowledge.

- Draw conclusions, make informed decisions, apply knowledge to new situations, and create new knowledge.

- Share knowledge and participate ethically and productively as members of our democratic society.

- Pursue personal and aesthetic growth.

The sub-standards are then organized into four categories:

- Skills - Key abilities needed for understanding, learning, thinking, and mastering subjects.

- Dispositions in Action - Ongoing beliefs and attitudes that guide thinking and intellectual behavior that can be measured through actions taken.

- Responsibilities - Common behaviors used by independent learners in researching, investigating, and problem solving.

- Self-Assessment Strategies - Reflections on one's own learning to determine that the skills, dispositions, and responsibilities are effective.

Each standard, category, and substandard is numbered. For instance,

1. Inquire, think critically, and gain knowledge.

1.1 Skills

1.1.1 Follow an inquiry-based process in seeking knowledge in curricular subjects, and make the real-world connection for using this process in own life.

Students are asked to "follow an inquiry-based process in seeking knowledge in curricular subjects, and make the real-world connection for using this process in own life".

The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) has also developed a set of standards. These National Educational Technology Standards (NETS) are used by both teacher librarians and technology coordinators in working with teachers. This ISTE sponsored web page focuses on news, resources, and guidelines for the National Educational Technology Standards. It also contains sample curriculum.

The major areas in the NETS for Students (2007) include:

- Creativity and Innovation. Students demonstrate creative thinking, construct knowledge, and develop innovative products and processes using technology.

- Communication and Collaboration. Students use digital media and environments to communicate and work collaboratively, including at a distance, to support individual learning and contribute to the learning of others.

- Research and Information Fluency. Students apply digital tools to gather, evaluate, and use information.

- Critical Thinking, Problem Solving, and Decision Making. Students use critical thinking skills to plan and conduct research, manage projects, solve problems, and make informed decisions using appropriate digital tools and resources.

- Digital Citizenship. Students understand human, cultural, and societal issues related to technology and practice legal and ethical behavior.

- Technology Operations and Concepts. Students demonstrate a sound understanding of technology concepts, systems, and operations.

Try It!

Try It!

Read the AASL Standards for the 21st-Century Learner.

Read the ISTE National Educational Technology Standards for Students.

Do you consider these standards complete or do you think some knowledge, skills, or dispositions are missing?

Compare and contrast these two different perspectives and sets of competencies.

Read!

Read!

Explore the online presentation Stong Nests, Successful Students: Skills & Strategies for 21st Century Learning by Annette Lamb. This article explores the standards and focuses on ideas for implementation.

Information Literacy Standards and Higher Education Instruction Today

In addition to the AASL and ISTE standards that address K-20 information literacy, the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL) have also developed Information Literacy Competency Standards specifically focused on the college level. The standards approved in 2000 include the following:

- Standard 1: The information literate student determines the nature and extent of the information needed.

- Standard 2: The information literate student accesses needed information effectively and efficiently.

- Standard 3: The information literate student evaluates information and its sources critically and incorporates selected information into his or her knowledge base and value system.

- Standard 4: The information literate student, individually or as a member of a group, uses information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose.

- Standard 5: The information literate student understands many of the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information and accesses and uses information ethically and legally.

Recently, six concepts anchor the new ACRL Framework. Under each of these categories are both knowledge practices and dispositions.

- Authority Is Constructed and Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Information Has Value

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

IMPORTANT!

IMPORTANT!

Read!

Read Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (February 2, 2015). Then, read From standards to frameworks for IL: How the ACRL Framework addresses critique of the standards by Nancy Foasberg (October 2015). This article explains the move from standards to frameworks.

Try It!

Try It!

Read Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. Compare this to the new Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.

Go to Information Literacy Standards, Performance Indicators, and Outcomes from ACRL.

The work of the ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards Task Force is ongoing. Check their page for the current status.

New standards are in the process of being introduced. First, there's a revised definition of information literacy.

Information literacy combines a repertoire of abilities, practices, and dispositions focused on expanding one’s understanding of the information ecosystem, with the proficiencies of finding, using and analyzing information, scholarship, and data to answer questions, develop new ones, and create new knowledge, through ethical participation in communities of learning and scholarship.

The framework for the new standards includes the following elements:

- core understandings about the evolving information system (threshold concepts)

- a set of practices that demonstrate increased credibility within that ecosystem, as both consumer of information and creator of knowledge (knowledge practices, metaliteracy)

- a way of thinking that develops more expert “moves” within that dynamic information ecosystem (dispositions, self-assessments)

- metacognitive strategies and critical reflection (metaliteracy, self-assessments)

At the core of the new information literacy competencies are threshold concepts. These are the key ideas and processes that define information literacy. For instance, "authority is constructed and contextual" and "searching is strategic".

Finally, the new standards demand metaliteracy the behaviorial, cognitive, affective, and metacognitive areas.

Standards have also been developed by organizations in countries around the world. For instance, the UK's Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) maintains information literacy standards. Go to Information Literacy: The Skills for a list of skills.

Content Area Standards, Inquiry and Instruction

Inquiry-based approaches can be found across content area.

Inquiry is closely related to reading and writing. According to Barbara Stripling in Curriculum Connections through the Library (2003, p. 7),

"unfortunately, reading instruction often stops after the decoding and fluency stages, yet developing increasingly sophisticated reading strategies can continue for a lifetime."

Inquiry-based instruction is a central theme of the National Science Standards (Inquiry and the National Science Teaching Standards) as well as state standards.

For example, Indiana Science Standard 5.1.2 states: "begin to evaluate the validity of claims based on the amount and quality of the evidence cited."

Inquiry is evident in other academic areas too. Indiana Social Studies 6.1.29 states:

"form research questions, and use a variety of information resources to obtain and evaluate historical data on the people, places, events, and developments in history of Europe and the Americas".

Similar standards can be found in English, Mathematics, and other areas. A seventh grade English standard asks students to "assess the adequacy, accuracy, and appropriateness or the author's evidence to support claims." Another asks students to "identify topics, ask and evaluate questions, and develop ideas"

Even kindergartners are asked to "explore, observe, ask questions, discuss observations, and seek answers."

Recently, all but a few states have adopted the Common Core State Standards. These provide consistency nationally, but also provide individual states with the flexibility to adapt the standards to meet their needs.

Recently, all but a few states have adopted the Common Core State Standards. These provide consistency nationally, but also provide individual states with the flexibility to adapt the standards to meet their needs.

Whether categorizing invertebrates, comparing characters in a novel, or conducting an in-depth investigation of a social issue, students need skills in observing, questioning, applying prior knowledge, evaluating information, making calculations, organizing ideas, drawing inferences, and reflecting on the process of thinking.

A primary focus of the Common Core is literacy in all its forms. The Common Core identified capacities of the literate individual (Common Core, Introduction, 7).

- They demonstrate independence.

- They build strong content knowledge.

- They respond to the varying demands of audience, task, purpose, and discipline.

- They comprehend as well as critique

- They value evidence.

- They use technology and digital media strategically and capably.

- They come to understand other perspectives and cultures.

The Common Core standards

"insist that instruction in reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language be a shared responsibility within the school." Common Core, Introduction, 4

The Common Core puts

"special emphasis on informational texts." One reason for this focus is the "extensive research establishing the need for college and career ready students to be proficient in reading complex informational text independently in a variety of content areas." Common Core, Introduction, 4

Watch!

Watch!

Browse the Common Core State Standards videos.

They provide an overview to each area.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to Common Core Standards Initiative.

Skim their Resources.

How do they connect with information skills?

Information Inquiry Across the Curriculum

An effective information literacy curriculum requires collaboration at many levels. Librarians must work with faculty to establish an integrated program of meaningful, standards-based activities. Teachers must work with other educators across grade levels and content areas. In other words, the information literacy curriculum must be aligned both horizontally and vertically to ensure that knowledge and skills are introduced, reinforced, and mastered across content areas and grade levels.

Information inquiry is a topic that weaves through the standards of all subject areas. Notice how the standards below relate directly to the information literacy standards.

Let's use the Indiana Academic Standards as an example. Examine the Social Studies and Science standards below. Can you find Library Information Literacy Standards that connect to these content-specific standards?

Social Studies Standard 4.1.26 Generate questions and seek answers about people, places, and events using primary source and secondary source materials.

Social Studies 7.1.32 Identify and evaluate solutions and alternative courses of action chosen by people to resolve problems that have confronted people during various periods in the history of Africa, Asia, and Australia/Oceania.

Science 7.2.8 Question claims based on vague attributes such as "Leading doctors say..." or on statements made by celebrities or other outside the area of their particular expertise.

According to Barbara Stripling in Curriculum Connections through the Library (2003, p. 6),

"inquiry is not a collection of process skills and content; it is a relationship between thinking skills and content. Learner are, therefore, engaging in scientific inquiry, historical inquiry, social inquiry, literary inquiry, aesthetic inquiry, and other types of inquiry."

Inquiry can be applied across the curriculum with discipline-specific process skills. There are many ways to connect information and technology literacy skills to content area standards.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to Literacy with ICT Across the Curriculum, browse the full document, and explore this outstanding website. The project is intended to help educators understand the role of information and technology in teaching and learning. Designed for Manitoba Canada teachers, the approach provides an excellent framework for developing information and technology skills.

University faculty have discipline-specific ideas regarding how they define information literacy and the skills they think their students need.

Read!

Read!

Read one of the followin articles:

Do we speak the same language? A study of faculty perceptions of information literacy by Johnathan Cope and Jesus Sanabria (October 2014).

Think about the importance of discipline-specific partnerships for a successful information literacy program.

OR

Teaching for transfer: reconciling the Framework with disciplinary information literacy by Rebecca Z. Kuglitsch (July 2015).

Needs Assessment and Analysis

After you've explored the standards, you're ready to assess the needs of your library users. It's easy to guess what learners need. However, it's much more effective to back up speculation with evidence.

After you've explored the standards, you're ready to assess the needs of your library users. It's easy to guess what learners need. However, it's much more effective to back up speculation with evidence.

Much time and energy is wasted on the development of instructional materials that are unnecessary and ultimately unused. It's important to carefully identify needs before jumping into instructional development.

Dick, Carey, and Carey (2011, 15-16) identified four common methods for identifying needs that will lead to instructional goals:

- Subject-Matter Expert Approach - Librarians have experience as information professionals and are aware of the knowledge and skills library users need to be successful. This information can be valuable in planning.

- Content Outline Approach - Standards and existing curriculum guidelines may dictate the content. Most states are now aligning instruction with the new Common Core standards.

- Administrative Mandate Approach - Sometimes authorities enact specific requirements for instance under the Children's Internet Protection Act schools are required to teach "minors appropriate online behavior".

- Performance Technology Approach - Most instructional designers prefer instructional goals that have been identified in response to a performance problem or instructional need.

A Performance Analysis is useful in identifying specific organizations problems. In some cases, these problems can be solved through instruction. Robinson and Robinson (1995) suggest the creation of a performance relationship map to visualize problem with desired outcomes. This is useful with internal training problems in libraries. For instance, a performance analysis might determine that the current instructional video used to train student worker in proper shelving techniques is ineffective.

A Performance Analysis is useful in identifying specific organizations problems. In some cases, these problems can be solved through instruction. Robinson and Robinson (1995) suggest the creation of a performance relationship map to visualize problem with desired outcomes. This is useful with internal training problems in libraries. For instance, a performance analysis might determine that the current instructional video used to train student worker in proper shelving techniques is ineffective.

A Needs Assessment is a process that helps the instructional designer identify the gap between the desired status of student performance and the current status. Identification of gaps is an effective way to determine needs. In other words, identify what you want students to be able to do. Collect information about current student skills. Finally, identify the gap between where you are and where you want to be.

Blanchett, Powis, and Webb (2012) recommend conducting a Training Needs Analysis (TNA). This process identifies a training gap and its related needs. First, current and future requirements for knowledge, skills, attitudes, and competencies are identified. Second, places are identified where training needs, knowledge, and gaps occur. These gaps can be based on data collection such as results of surveys such as student questionnaires, existing data such as evidence of plagiarism, or external review.

Read Making Assessment Less Scary by Nancy Goebel and others in College and Research Libraries (2013).

Read Making Assessment Less Scary by Nancy Goebel and others in College and Research Libraries (2013).

Think about how you could assessment learner needs.

When determining needs think about the broader issues related to information literacy as well as specific informational skills.

When considering the broader issues, think about economic impact, academic achievement, and social implications of information literacy. For instance, a 2007 UK study found that employees spend 6.4 hours per week seeking information. Of these searches, 37% are unsuccessful learning to billions of pounds/euros of time wasted each year.

Adults come to class with real-world needs and expectations such as the desire to complete a family history project or do well in a research class. Instruction is a solution for a performance-based problem. Learning isn't about "covering the textbook".

Example: A high school senior needs to be able to identify evidence and create arguments for a social issues debate. This person must learn to select and use specific electronic databases and websites. Then, locate and evaluate information from these resources.

Example: A library worker needs to be able to help users with library questions. This person must learn the required knowledge, skills, and dispositions so he or she can perform work duties.

Example: A health care worker needs to be able to find information on the latest emergency procedures. This person must learn to use information processes and resources related to this need.

Carefully examine the current status of your library instruction program.

Carefully examine the current status of your library instruction program.

- What's the role of your library in teaching and learning?

- How can your performance be improved?

- What knowledge and skills do your users currently possess?

- What knowledge and skills do you users need to possess?

Use a variety of tools for collection information to support instructional needs. These methods may include:

- Pre-tests - test student knowledge using open-ended and multiple choice questions

- Observations - observe user behavior and activities in the library

- Surveys - ask users about their knowledge, skills, and interests

- Standardized tests - analyze the results of to determine current skills

Try It!

Try It!

Go to Inspiring Learning Quick Checklist (PDF) or Detailed Framework (PDF) from the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council. Think about a particular library and how you would identify priority areas. Then, explore the detailed checklists related to People, Places, Partnerships, and Policies.

Research to Support Instructional Needs

An increasing body of research is being conducted to examine the needs of learners related to information skills. Use this information to provide evidence to support your instructional programs.

Lee, Paik, and Joo (2012) studied student resource selection through the examination of self-generated diaries. Their findings provide insights into the skills undergraduates need related to information resource selection. They found that

"to enhance accessibility and familiarity to these sources, information literacy education would be important. Information literacy courses can emphasize the advantages of using these reliable sources and teach students how to access and use them... Through information literacy education, we could train undergraduates to develop effective search strategies and help them select information resources that fit those search strategies."

In a study of secondary science classrooms, Julien and Baker (2009) found that even in situations where information literacy curricula are mandated, many students lack information searching and evaluation skills. They found that pressures to cover large amounts of content may be causing teachers to overlook essential information skills instruction.

In a study of secondary science classrooms, Julien and Baker (2009) found that even in situations where information literacy curricula are mandated, many students lack information searching and evaluation skills. They found that pressures to cover large amounts of content may be causing teachers to overlook essential information skills instruction.

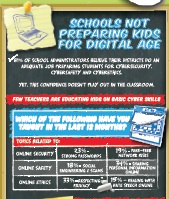

You don't always need to wade through volumes of data for an overview of needs. Examine the CyberEducation infographic on the right from StaySafeOnline (it's a large file, so it will take a little while to download).

Some of the best research for high school and academic librarians is being conducted by Project Information Literacy with funding from a number of organizations.

For research related to Internet skills, go to StaySafeOnline and examine their research such as the National K-12 Study Fact Sheet.

Read!

Read!

Read one of the following articles:

Bridging the information literacy communication gap: putting PIL studies to good use by Steven Bell.

This article provides an excellent overview of the research conducted by Project Information Literacy. Think about how the information in this article could be used to justify the information literacy curriculum.

OR

How Teens Do Research in the Digital World by Kristen Purcell and others (2012).

Based on this report, think about the specific information skills students need.

Try It!

Try It!

It's essential to base instruction on learning needs. Rather than relying on "gut" feelings, support your teaching with specific research. For instance, in the Purcell (2012) study teachers indicated that only 17% of students are "very likely" to use online databases for a typical research project, while 94% are very likely to use Google.

Why don't students use online databases? How can you change their behavior through instruction?

Select a specific problem or need identified in the research and think about instructional solutions.

High School and College Needs

As students mature as information users, their needs change. It's important that librarians carefully assess student need as they move through high school and college.

As students mature as information users, their needs change. It's important that librarians carefully assess student need as they move through high school and college.

Gilbert (2009) used an assessment model to create a "snapshot of students" as they entered college. She found that students came to college with a range of research and library experiences. Gilbert used a pretest to collect data about student information skills prior to beginning an information literacy course. A posttest was used at the end of the course.

Smith and others (2013) conducted a study assessing the gap in high school students’ readiness for undergraduate academics. They found that high school students did not possess the information literacy skills necessary to be successful in college.

In A transition checklist for high school seniors, Owen (2010, 20) describes the research skill weaknesses of students entering college. They include:

- lack of general knowledge

- difficulty defining research questions and following the research process

- problems searching for information

- trouble evaluating and using information

In They can find it, but they don't know what to do with it: Describing the use of scholarly literature by undergraduate students, Rosenblatt (2010) found that upper-division undergraduate students can conduct searches, evaluate information, and select items to meet their research needs regardless of whether they have had library skills instruction. However the author is concerned that

"many of these students appear to have difficulty using the information they have found in a critical way. Half of the students involved in this study (20 in total) provided little or no evidence that they derived any benefits from the literature they were required to consult. Shouldn't we, as instructional librarians, be concerned about students' abilities to use the information they have discovered?... by analyzing the work products of our students, we can reveal their misconceptions about the research process and why the "literature" is cited in academia. By collaborating with faculty staff, we as librarians can also identify differences between faculty conceptions of the purpose of research and those of their students. If it cannot be assumed that students understand why certain types of sources are used or even why a learned person reads existing research, then how do we know that students are learning by conducting research and writing papers? " (Rosenblatt, 2010, 60)

Read!

Read!

Read one of the following articles:

A transition checklist for high school seniors by Patricia Owen.

It provides a checklist useful to both school and academic librarians as they help seniors transition from high school to college.

OR

A New Curriculum for Information Literacy by Secker and Coonan (July 2011). This article describe a curriculum for teaching information literacy. The appendix provides some excellent resources for an evidence-based approach to teaching.

OR

Critical thinking, information literacy and quality enhancement plans by Jacalyn Bryan (2014).

Workplace Needs

Consider the information-seeking behaviors and needs of those entering the workforce. How can libraries prepare recent graduates as well as those re-entering the workforce?

Head (2012) interviewed employers from major companies as well as recent college graduates about information seeking behavior and skills. She found that

"the basic online search skills new college graduates bring with them are attractive enough to help them get hired. Yet, employers found that once on the job, these educated young workers seemed tethered to their computers. They failed to incorporate more fundamental, low-tech research methods that are as essential as ever in the contemporary workplace." (2012, 3)

Employers expect students to have information proficiencies and place "a high premium on graduates' abilities for searching online, finding information with tools other than search engines, and identifying the best solution from all the information they had gathered." (2012, 3) They found that new hires had technology skills, however they lacked the patience and persistence needed to solve problems that go beyond basic web searches. Many employers were surprised that new hires rarely used traditional resources such as the phone or print documents. They found that recent graduates compensate by forming relationships with experienced co-workers to locate information.

According to Head (2012, 12), employers say that college hires lack the following information competencies:

- Engaging team members during the research process

- Retrieving information using a variety of formats

- Finding patterns and making connections

- Taking a deep dive into the "information reservoir"

They also found that employees face real-world information challenges. Recent graduates are faced with short deadlines, little direction, and the need to use human-mediated sources to address highly contextual questions.

Finally, they identified the following competencies from college that were most applicable in the workplace (Head, 2012, 20):

- An approach to systematically evaluating research sources

- Ability to critically read and analyze print sources

- Ability to synthesize large volumes of content and extract quality information

- The process of implementing an iterative research strategy by framing questions

Information skills were found to be a part of almost every career path (Head, 2012, 16):

"Almost all of the participants agreed that a primary part of their jobs required them to find, evaluate, and use information to solve problems. They said many of these problems seemed to appear randomly and quickly on their desks during the course of a workday."

Looks for other ideas for identifying needs? Check out the following YouTube PIL Channel videos focusing on recent Project Information Literacy studies:

- Major Findings: The PIL Technology Study

- Major Findings: The PIL 2010 Student Survey

- Major Findings: The PIL Handout Study

- PIL InfoLit Dialog #1: Wikipedia

- PIL InfoLit Dialog #2: Procrastination

- PIL InfoLit Dialog #3: Frustrations

- PIL InfoLit Dialog #4: Strategies

- PIL InfoLit Dialog #5: Finding Context

- The Student Discussions

- Understanding Information Literacy through the Lens of the Student Experience

- It's Complicated: What Students Say About Research and Writing Assignments

Try It!

Try It!

Watch the YouTube video on PIL's Day After Graduation Study (2012).

Brainstorm ways that school, academic, special, and public libraries all need to be involved with workplace information literacy.

Needs from a Student Perspective

Some students aren't aware of the direct connection between their efforts on skills assignments and learning. It's important to reinforce effort. In a study of college students, Gross and Latham (2011) found

"the idea that information is something they are all naturally good at and that no 'real' skills is involved in finding, evaluating, and using information is pervasive. This attitude presents real barriers that instructional librarians in academic libraries face."

Although many young people consider themselves technology-savvy, they may not possess the information skills needed to succeed in the 21st century. In a study by Foster (2006), only 13 percent of high school and college students who took the ETS Information and Communication Technology tested were identified as information literate.

In reviewing the literature on information literacy, Gross and Latham (2009, 336) found that

"students who receive information literacy instruction do not necessarily learn, or retain, what is taught. While this in itself may not be surprising, what is surprising is that students who are unable to demonstrate information literacy competency nevertheless exhibit a high level of confidence in their ability to find and use information effectively."

Competency theory suggests that people tend to overestimate their skills, particularly in areas where people commonly have some comfort such as information literacy. Gross and Latham (2009, 337) notes that "when people gain skills in a domain, they are better able to assess their own skill level, recognize the abilities of others, and make better estimations of their own performance."

Gross and Latham (2011, 183) suggest that "tests of ability may be the only way to differentiate the proficient from the below-proficient, and instructional librarians may want to consider increased us of pre- and post-tests around instructional activities."

Read!

Read!

Read Undergraduate Perceptions of Information Literacy: Defining, Attaining, and Self-Assessing Skill (PDF) by Melissa Gross and Don Latham (2009).

OR

Read Experiences with and Perceptions of Information: A Phenomenographic Study of First-Year College Students (PDF) by Melissa Gross and Don Latham (2011).

Curriculum Mapping

To build an effective collection, collaborate with teachers, and design engaging instructional materials, a librarian must have a grasp of the entire curriculum. This involves mapping the library collection and the curriculum. Then, using this experience and resource as the blueprint for designing instructional materials.

To build an effective collection, collaborate with teachers, and design engaging instructional materials, a librarian must have a grasp of the entire curriculum. This involves mapping the library collection and the curriculum. Then, using this experience and resource as the blueprint for designing instructional materials.

- Collection Map - a visual representation of the collection

- Curriculum Map - a visual representation of the curriculum

In Librarian Morphs into Curriculum Developer, Charlotte C. Vlasis (2003, p. 108-109) describes a curriculum map as

"a visual picture of the subjects and skills taught during a school year... a curriculum map show where you are with the curriculum, where you need to go, and how you will get there".

It includes rows and columns containing the standards, content, skills, resources, and assessment for a particular grade level. It may also be "calendar-based" focusing on activities week-by-week or month-by-month.

Watch!

Watch!

View What is Curriculum Mapping? and Four Phases of Curriculum Mapping with Heidi Hayes Jacobs on YouTube.

Think about how curriculum mapping can be used to merge the information skills curriculum with content-area curricula.

Vlasis describes two types of curriculum maps:

- Integrated Maps. Shows all subjects that a child is taught each day.

- Content Maps. Shows one subject area and is broken down into specific parts or subtopics.

A curriculum map is a living document used for examining and improving the curriculum. The process of creating the map leads to a better understanding of the content, skills, and assessments. It's also a means of holding teachers accountable for the material they are required to teach. The activity of curriculum making can foster an atmosphere of sharing, teamwork and collaboration. It is particularly useful for new teachers as they adjust to the school's requirements. It's useful for experienced teacher as they look for ways to build skills from one grade to the next. Finally, the process of curriculum mapping helps address concerns about overlap and repetition in the curriculum. Teachers often have heated discussions about when a particular book might be real-aloud in a class. Through discussions about developmental appropriateness, teachers can come to agreements about the placement of particular materials.

It's essential that the school library be involved in curriculum mapping. Otherwise the resources listed in the curriculum map are often simply pages from a textbook. The librarian can draw on a wide range of materials in the physical and virtual collection to enhance the curriculum map with developmentally appropriate materials that address the content needs. This activity provides a wonderful opportunity for teacher-librarian collaboration.

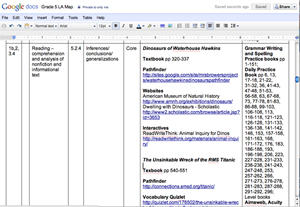

Examine an excerpt from a fifth grade language arts curriculum map (click image below to enlarge). By using Google Docs, teachers are able to work collaboratively on the document.

Curriculum mapping provides valuable information to the school librarian about what it taught in the building and what resources are needed. The librarian can use the curriculum map to envision cross-grade level activities and interdisciplinary projects that individual teachers might not see when simply examining their own grade level and subject area. The map is also useful in budget planning and working with administrators on where additional resources are needed.

Curriculum mapping and collection mapping go hand-in-hand. As media specialist learn more about the curriculum, collection mapping activities become more relevant. It becomes more clear what areas of the collection need to be revised or updated.

Vlasis describes a process for using the curriculum map as part of co-planning instructional units with teachers.

- Standards. Select appropriate standards for the grade level and subject area.

- Brainstorming. Explore a range of activities.

- Essential Questions. Focus on essential questions that reflect the standards.

- Assessment. Plan assessments that provide evidence of learning.

- Activities. Plan lessons that reflect the needs of students.

- Post-Unit Reflection. Think about how the unit went and what can be changed for future collaborations.

Read Building Partnerships: Transforming Learning through Data-Drive Collaboration by Annette Lamb for examples of how the school librarian can become an important part of curriculum planning and evidence-based programs.

Instructional Goals

Your needs should inform your instructional goals.

Your needs should inform your instructional goals.

According to Dick, Carey, and Carey (2011, 15),

"perhaps the most critical event in the instructional design process is identifying the instructional goal. If done improperly, even elegant instruction may not serve the organization's or the intended learners' real needs. Without accurate goals designers run the risk of planning instructional solutions for which needs do not really exist."

Before designing or enhancing instruction, it's important to ask yourself about your purpose. National and international standards describe the outcomes of instruction in terms of student performance. These are the basis for your instructional goals.

Ask yourself, what do you expect students to be able to know and do as a result of instruction? How does this relate to the national standards?

Words like understand, know, and appreciate are often used in writing these broad instructional goals. Later, the learning objectives will focus on the specifics. However, Dick, Dick, and Carey (2011, 24-25) state that

"a fuzzy goal is generally some abstract statement about an internal state of the learner, such as 'appreciating,' 'having an awareness of,' 'sensing,' and so on. These kinds of terms often appear in goal statements, but the designer doesn't know what they mean because there is no indication of what learners would be doing if they achieved this goal."

Vague goals should be re-examined. Think about what the learner would actually be doing when performing the goal. These actions should be stated in the revised goal. This may seem like an unnecessary step, however a proper worded goal can determine the success of an instructional program.

Examples

- Vague Goal - Be aware of how to deal with information overload.

- Revised Goal - Demonstrate techniques for narrowing a topic when using a search engine such as Google.

- Vague Goal - Understand how to change the printer cartridge.

- Revised Goal - Demonstrate how to properly remove and replace a printer cartridge.

- Vague Goal - Know about citations.

- Revised Goal - Create complete citations using proper MLA format for a book, website, and journal article.

Instructional goals can be classified into four domains of learning (Lamb, 1993). It's important to identify the domain of learning of your instructional goal. The domain of learning will affect your approach to instructional design, and later, the instructional strategies you choose.

- Intellectual Skills enable the learner to do some unique, cognitive activities (i.e., the ability to make discriminations, name new instances or concepts, apply rules, and solve problems).

Example Goal: Given a calculator and a list of times, the learner will be able to calculate sales tax.

- Verbal Information goals are different from intellectual skills in the verbal information enables the learner to simply state, list, describe, or recall the "gist" of something. Students do not actually come up with new ideas, draw comparisons, or apply rules.

Example Goal: Given a list of cities, the learner will be able to name the state for which each is the capital. - Psycho motor Skills involve both mental and physical activities to achieve specific results

Example Goal: The learner will be able to set up and operate a video camera. - Attitudes enable the learner to make particular choices. Or they may enable the learner to make decisions to act under particular circumstances.

Example Goal: The learner will choose to read poetry as a leisure activity.

Dick, Carey, and Carey (2011, 33) suggest the following criteria for evaluating instructional goals.

- Is/are the instructional goal statement(s):

- Linked clearly to an identified problem in the organization

- Linked clearly to documented performance gaps?

- Clearly a solution to the problem?

- Acceptable to those who approve the instructional effort?

- Do the instructional goal statement(s) describe the:

- Actions of the learners (what they will do)?

- Content clearly?

- Intended learner?

- Performance context?

- Tools available to the learners in the performance context?

If you're working with an English or Social Studies teacher, the goal might combine information literacy skills with content-area standards related to persuasive writing or evaluating political messages.

Try It!

Try It!

Select a library situation and instructional need.

Practice writing instructional goals.

Identifying standards, needs, and goals are important first steps in the instructional design process.

Resources

AASL (1998). Information Power. ALA.

Bell, Steven (November 2011). Bridging the information literacy communication gap: putting PIL studies to good use. Library Issues, 32(2).

Blanchett, Helen, Powis, Chris, & Jo Webb (2012). A Guide to Teaching Information Literacy: 101 Practical Tips. Facet Publishing.

Bryan, Jacalyn E. (2014). Critical thinking, information literacy and quality enhancement plans. Reference Services Review. 42(3), 388-402.

DeSaulles, M. (2007). Information literacy amongst UK SME: an information policy gap. Aslib Proceedings, 59(1), 68-79.

Cope, Jonathan & Sanabria, Jesus E. (October 2014). Do we speak the same language? A study of faculty perceptions of information literacy. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(4), 475-501.

Dick, Walt, Carey, Lou, and Carey, James O. (2011). The Systematic Design of Instruction. Seventh Edition. Pearson.

Donham, Jean (2010). Enduring Understandings - Where Are They in the Library's Curriculum? Teacher Librarian, 38(1).

Everett, Jo Ann (2003). Curriculum mapping and collection mapping. In B. Stripling, and S. Hughes-Hassell, Curriculum Connections through the Library.

Foasberg, Nancy M. (October 2015). From standards to frameworks for IL: How the ACRL Framework addresses critique of the standards. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(4), 699-717.

Foster, Andrea L. (October 27, 2006). Students Fall Short on 'Information Literacy,' Education Testing Service's Study Finds, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 53(10), A36.

Gilbert, Julie K. (2009). Using assessment data to investigate library instruction for first year students. Communications in Information Literacy, 3(2), 181-192.

Goebel, Nancy, Knoch, Jessica, Thomson, Michelle Edwards, Willson, Rebekah, and Sharun, Sara (2013). Making assessmet less scary. College and Research Libraries, 74(1), 28-31.

Gross, Melissa & Latham, Don (2009). Undergraduate perceptions of information literacy: defining, attaining and self-assessing skills. College and Research Libraries, 70(4), 336-350.

Gross, Melissa & Latham, Don (2011). Experiences with and perceptions of information: a phenonmenographic study of first-year college students. Library Quarterly, 81(2), 161-186.

Head, Alison J. (October 16, 2012). How College Graduates Solve Information Problems Once They Join the Workplace. IMLS/Harvard. Available: http://projectinfolit.org/pdfs/PIL_fall2012_workplaceStudy_FullReport.pdf

Jacobs, Heidi Hayes (1997). Mapping the Big Picture: Integrating Curriculum and Assessment K-12. ASCD.

Julien, Heidi & Baker, Susan (January 2009). How high-school students find and evaluate scientific information: A basis for information literacy skills development. Library & Information Science Research, 31(1), 12–17.

Kuglitsch, Rebecca Z. (July 2015). Teaching for transfer: reconciling the Framework with disciplinary information literacy. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 15(3), 457-470.

Lamb, Annette (1993). IBM Linkway Authoring Tool. Career Publishing.

Lee, Jee Yeon, Paik, Woojin, & Joo, Soohyung (March 2012). Information resource selection of undergraduate students in academic search tasks. Information Research, 17(1). Available: http://informationr.net/ir/17-1/paper511.html

Owen, Patricia (April 2010). A transition checklist for high school seniors. School Library Monthly, 14(8), 20-23.

Purcell, Kristen, Rainie, Lee, Heaps, Alan, Buchanan, Judy, Friedrich, Linda, Jacklin, Amanda, Chen, Clara, & Zickuhr, Kathryn (November 1, 2012). How Teens Do Research in the Digital World. Pew Internet.

Robinson, D. G. & Robinson, J.C. (1995). Performance Consulting: Moving Beyond Training. Berrett-Koehler.

Rosenblatt, S. (2010). They can find it, but they don't know what to do with it: Describing the use of scholarly literature by undergraduate students. Journal of information literacy, 4(2), pp 50-61. Available: http://ojs.lboro.ac.uk/ojs/index.php/JIL/article/view/LLC-V4-I2-2010-1

Secker, Jane & Coonan, Emma (July 2011). A New Curriculum for Information Literacy. Available: http://ccfil.pbworks.com/f/ANCIL_final.pdf

Smith, J. K., Given, L. M., Julien, H., Ouellette, D., & DeLong, K. (2013). Information literacy proficiency: Assessing the gap in high school students’ readiness for undergraduate academic work. Library & Information Science Research, 35(2), 88–96.

Stowe, B. (2013). Designing and implementing an information literacy instruction outcomes assessment program. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 20(3-4), 242–276.

Vlasis, Charlotte C. (2003). Librarian morphs into curriculum developer. In B. Stripling and S. Hughes-Hassell, Curriculum Connections through the Library.