Learning Theory

At the completion of this section, you should be able to:

- describe three psychology movements and researchers who contributed learning theories.

- discuss how learning theories can be applied to teaching information topics.

- describe the role of intelligences in learning.

- incorporate key ideas found in the literature related to learning theories into instructional materials.

Begin by viewing the class presentation in Vimeo. Then, read each of the sections of this page.

Explore each of the following topics on this page:

- The Big Picture

- Learning Theories

- Expert vs Novice Learners

- Learning Theory and Instruction

- Resources

The Big Picture

An understanding of students and how they learn is essential in developing instruction. This involves an understanding of psychology and learning theory. In addition, instructional developers need to understand the difference between novice and expert learners and how students mature as information users.

Learning is the process of acquiring new knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values. Intellectual processes are used to help individuals store and access information.

Learning is the process of acquiring new knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values. Intellectual processes are used to help individuals store and access information.

The roots of learning theory originate in the field of psychology. During the 19th century psychology emerged as a science. Three movements have shaped current thinking about how people learn: behaviorism, cognitive, and constructionist.

Behaviorism

Rooted in psychology, behaviorist theory focuses on objective observation of human behavior. Tasks are analyzed and procedures are developed to teach sub-tasks. Feedback and reinforcement is provided to assist in learning and motivation. Tests check for mastery at each stage. Students generally work independently. Many of the early studies were conducted in laboratories with careful controls.

In teaching, instructional designers create a series of short lessons based on specific tasks such as use of Boolean commands or creation of citations. Students are presented with information and given opportunities for hands-on practice. Praise is given for correct answers and useful feedback is provided for incorrect responses. Students work their way through exercises until they achieve mastery.

The roots of behaviorism began in the 19th century with people like Edward Thorndike.

Ivan Pavlov (shown left) is known for his theory of classical conditioning that he studied in dogs.

Ivan Pavlov (shown left) is known for his theory of classical conditioning that he studied in dogs.

John B. Watson was a psychologist who focused on animal behavior and child studies coining the term "behaviorism" around 1913.

B.F. Skinner (below left) was a psychologist active in the 1960s and early 1970s who is known for inventing the philosophy of radical behaviorism. He believed that behaviors are causal factors influenced by consequences. Behaviors are strengthened by positive reinforcement. Negative reinforcement strengthens behavior by removal of some adverse event. Reinforcement increases behavior.

Skinner advocated the use of teaching machines to administer programmed instruction. Many of his ideas about reinforcement are incorporated into instructional software today where tasks are broken into small, manageable pieces. He advocated active learning in that he expected students to perform rather than passively watch a teacher. However the teacher is ultimately in control in a behaviorist classroom evaluating learners and prescribing instruction. Skinner introduced the Skinner Teaching Machine (see below center). His ideas are still used in computer-based tutorials today.

Cognitive

The area of cognitive psychology emerged in the 1950s in response to behaviorism. Cognitivists argued that the way people think impacts behavior. They stress that humans generate knowledge and meaning through the sequential development of abilities. Learners need scaffolding to develop schema.

In teaching, instructional designers stress motivation and active learning in problem solving. Lessons should be designed around conceptual frameworks such as research process models. Organize materials into meaningful chunks. Provide learners with thinking tools such as advanced organizers (Davis Ausubel), concept mapping (Joseph Novak) mnemonics, and note-taking guides. Involve students in reflection and other metacognitive activities that involve students in monitoring and directing their own learning.

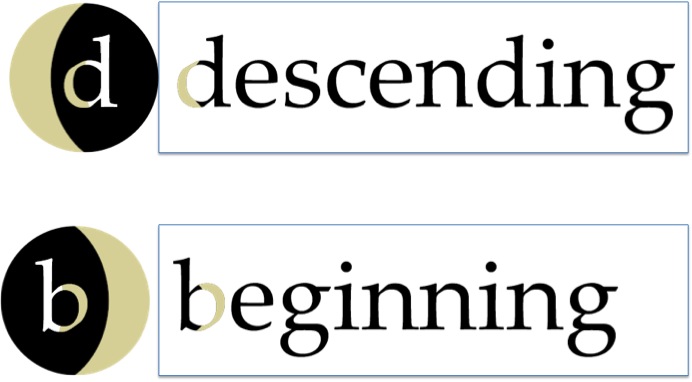

Mnemonics are used to remember whether the moon is beginning or descending.

Jean Piaget was a developmental psychologist known for his work with children. Through observation of children, he identified different stages of intellectual development in children. In learning, he stressed the importance of maturation.

Albert Bandura is a psychologist known for making the transition from behaviorism to cognitive psychology. He is responsible for social learning theory which states that people learn within a social context. He proposed that observational learning occurs through watching live models, verbal instruction, and symbolic modeling through media such as video. People react to the environment and interactions with people.

Jerome Bruner is a psychologist is known for his work in developmental psychology. He coined the term scaffolding to describe how learners build on existing knowledge. He believed that students could learn any materials that was organized appropriately.

Edgar Dale was an educator who is known for his Cone of Experience. Introduced in 1946, the Cone of Experience is a visual device that classifies types of mediated learning experiences into ten categories: direct, purposeful experiences, contrived experiences, dramatic participation, demonstrations, field trips, exhibits, motion pictures, radio/recordings/still pictures, visual symbols, and verbal symbols. The cone moves from concrete experiences at the bottom to abstract representations at the top of the cone.

Constructivism

Constructivism is a learning theory focusing on the way people create meaning through a series of individual constructs or experiences. It places emphasis on providing a learning environment where students can explore, test, and acquire new knowledge on their own. Each person creates their own mental models to deal with new information and experiences.

Constructivism is a learning theory focusing on the way people create meaning through a series of individual constructs or experiences. It places emphasis on providing a learning environment where students can explore, test, and acquire new knowledge on their own. Each person creates their own mental models to deal with new information and experiences.

Constructivism involves the process of questioning, exploring, and reflecting. This theory says that learners should construct their own understanding and knowledge of the world through varied experiences. By reflecting on these experiences, students assimilate useful information and create personal knowledge.

According to Barbara Stripling in Curriculum Connections through the Library (2003, p. 4), in a constructivist learning environment "students are expected to ask questions and seek new understandings; teachers are expected to change their roles from providers of information to provokers and guides of student learning".

Social constructivism stresses the importance of the dynamic interaction between the learner, teacher, and the task. It also stresses collaboration among learners.

In teaching, instructional designers provide authentic, meaningful tasks that allow students to explore and analyze information. By providing varied examples, real-world information, and alternative perspectives, students are able to join new information with prior knowledge to build new connections.

In teaching, instructional designers provide authentic, meaningful tasks that allow students to explore and analyze information. By providing varied examples, real-world information, and alternative perspectives, students are able to join new information with prior knowledge to build new connections.

For instance, Benjes-Small and others (2013) applied constructivist principles to develop a series of web evaluation lessons that involved students in creating and applying their own evaluation criteria.

Students are encouraged to participate in social interactions, discussions, and information exchanges. Through collaboration, students are able to solve problems under the guidance of a facilitator. Synergy is created when students, classmates, and teacher work together.

Many active teaching and learning techniques reflect the constructivist approach. These include problem-based learning, real-world simulations, case study approaches, and scientific experiments. Metacognition, or thinking about thinking is an important activity in the constructivist classroom. Students are encouraged to constantly raise questions and explore ideas.

Callison (2006, 334-336) identified key characteristics of a constructivist approach to learning:

- Constructivists believe that knowledge is constructed, not transmitted.

- Knowledge construction results from activity, so knowledge is embedded in activity.

- Knowledge is anchored in and indexed by the context in which the learning activity occurs.

- Meaning is in the mind of the knower.

- There are multiple perspective on the world.

- Meaning making is prompted by a problem, question, confusion, disagreement, or dissonance (a need or desire to know) and so involves personal ownership of that problem.

- Knowledge building requires articulation, expression, or representation of what is learned (meaning that is constructed).

- Meaning also may be shared with others, so meaning making also can results from conversation.

- Meaning making and thinking are distributed throughout our tools, culture, and community.

- Not all meaning is created equally.

John Dewey (shown below left) was a psychologist and educational reformer who argued that learning is an interactive and social process. He believed that students thrive in environments where they are active learners. Experiential learning involves students in exploring, thinking, and reflecting through real-world experiences.

Lev Vgotsky was a psychologist who described a Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). He theorized that a low level of skill can be reached by a child working independently. A high level of skill is possible when working with a skilled instructor. In other words, a child can reach beyond their maturational level with assistance from others.

Maria Montessori (shown below right) advocated learning environments where students are independent learners who learning through discovering concepts rather than direct instruction.

Try It!

Try It!

Complete Constructivism as a Paradigm for Teaching and Learning the free, online workshop from Educational Broadcasting Corporation.

Read!

Read!

Read Riehle, Catherine Fraser (2012). Inciting curiosity and creating meaning: teaching information evaluation through the lens of ‘bad science’. Public Services Quarterly, 8, 227-234.

Learning Theories

Our student population is diverse. It's important to design a learning environment to meet the individual differences of inquiring minds. What motivates one student might bore another. What is meaningful in one context, might be misunderstood in another. By understanding student thinking processes, intelligences, and learning styles, teachers can develop individual paths of learning.

Learning styles and theories help instructional designers and educators understand the processes students use to gather, evaluate, and use information.

Claxton and Murrell (1987) described four categories:

- Personality Models - refers to an individual's personality such as introverted/extroverted, thinking/feeling, judging/perceiving (i.e., Myers-Briggs Type Indicator)

- Information Processing Models - refers to channels or modes of communication used by learners such as visual, verbal, auditory, kinesthetic (i.e., VARK, Felder/Silverman, multiple intelligences)

- Social Interaction Models - refers to how learning is impact by contexts

- Instruction Preference Models - refers to how learners deal with different teaching methods such as lecture or discussion.

Many theories associated with intelligence, learning styles, and related topics have been developed over the past couple decades.

Brain-based Learning

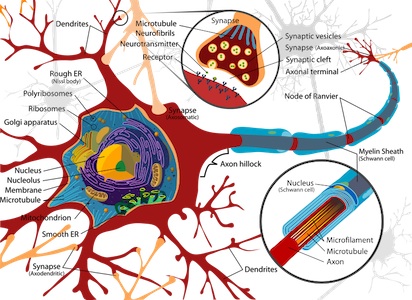

Brain-based learning is based on the structure and function of the brain. Theories stress that learning occurs through the active processing of information.

Brain-based learning is based on the structure and function of the brain. Theories stress that learning occurs through the active processing of information.

In teaching, students are placed in immersive, real-world experiences that involve complex challenges. Students are given access to both the "big picture" and details needed to solve problems. Feedback comes from the results of authentic situations.

Brain-based learning has been called a combination of brain science and common sense. Hart (1983) called the brain "the organ of learning." He advocated learning more about the brain in order to design effective learning environments.

Caine and Caine (1991) developed twelve principles that apply what we know about the function of the brain to teaching and learning. These principles were derived from an exploration of many disciplines and are viewed as a framework for thinking about teaching methodology. Read Caine and Caine's (1994) Mind/Brain Learning Principles for the principles with brief descriptions. The principles are:

- The brain is a complex adaptive system.

- The brain is a social brain.

- The search for meaning is innate.

- The search for meaning occurs through patterning.

- Emotions are critical to patterning.

- Every brain simultaneously perceives and creates parts and wholes.

- Learning involves both focused attention and peripheral attention.

- Learning always involves conscious and unconscious processes.

- We have at least two ways of organizing memory.

- Learning is developmental.

- Complex learning is enhanced by challenge and inhibited by threat.

- Every brain is uniquely organized.

For complex learning to occur, Caine and Caine have identified three conditions:

- Relaxed alertness - a low threat, high challenge state of mind

- Orchestrated immersion - an multiple, complex, authentic experience

- Active processing - making meaning through experience processing

The nine brain-compatible elements identified in the ITI (Integrated Thematic Instruction) model designed by Susan Kovalik include: Absence of Threat, Meaningful Content, Choices, Movement to Enhance Learning, Enriched Environment, Adequate Time, Collaboration, Immediate Feedback, and Mastery (application level).

Cognitive Load Theory

John Sweller (1988) described the importance of understanding human cognitive architecture. His theory involves three types of memory that are interrelated and important for long-term memory.

- Intrinsic Cognitive Load - some concepts are inherently difficult to teach and learn, so they must be broken down into "subschema" that are taught separately then brought back together into a whole.

- Extraneous Cognitive Load - some concepts can be taught a number of ways, but are best learned without unnecessary information that use up working memory. In other words, concentrate attention on the most important elements.

- Germane Cognitive Load - focus on learning experiences that stress processing information, construction, and automation of schemas.

Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning focuses on how people store multimedia information.

Richard Mayer notes that humans can only process finite amounts of information in a channel (i.e., visual, auditory) as they create mental representations. Three memory stores including sensory (receives and stores information for a very short time), working (actively processes information to create schema) and long-term (permanent storage of information) are important in learning.

The model is based on three assumptions:

- visual and auditory information and experiences are processed through separate channels

- processing channels are limited in their ability to process information

- processing information within channels is an active process designed to construct mental representations

Mayer's research into multimedia culminated in a number of principles:

- Multimedia Principle. Students learn better from words and pictures than from words alone.

- Spatial Contiguity Principle. Students learn better when corresponding words and pictures are presented near rather than far from each other on the page or screen

- Temporal Contiguity Principle. Students learn better when corresponding words and pictures are presented simultaneously rather than successively.

- Coherence Principle. Students learn better when extraneous words, pictures, and sounds are excluded rather than included.

- Modality Principle. Students learn better from animation and narration than from animation and on-screen text.

- Redundancy Principle. Students learn better from animation and narration than from animation, narration, and on-screen text.

- Individual Differences Principles. Design effects are stronger for low-knowledge learners than for high-knowledge learners and for high spatial learners rather than from low spatial learners.

Think about how the image below fits into the principles above.

Component Display Theory

David Merrill classified learning in two dimensions:

- Types of Content - fact, concept, procedure, principle

- Levels of Performance - remembering, using, generalities

Merrill suggests that learning is more effective if all three levels of performance are present. Merrill's theory identified primary and secondary presentation forms:

- Primary forms - rules, examples, recall, practice

- Secondary forms - prerequisites, objectives, helps, mnemonics, and feedback

Experiential Learning

David Kolb developed a four-stage cycle of learning to show how experience is translated into concept formation.

- Do - concrete experience (learner actively experiences an activity)

- Observe - reflective observation (learner actively reflects on the experience)

- Think - abstract conceptualization (learner develops a theory or model of what is observed)

- Plan - active experimentation (learner tried out the theory)

As a result of observing this learning cycle, Kolb identified four learning styles corresponding to these stages:

- assimilators - learn best when presented with logical theories

- convergers - learn best when provided practical applications of theories

- accommodators - learn best when provided "hands-on" experiences

- divergers - learn best when observing and collecting information

Gender Theory

In biology, gender refers to the sexual distinction between males and females. However in social sciences and specifically education, the term gender also focuses on the social, cultural, and psychological distinctions between boys and girls.

Over the past several decades, gender research has increased our understanding of the differences and similarities between the genders. Tilley and Callison (2006, 384) in their exploration of research on gender differences related to information inquiry found:

- girls identify and deal with personal information overload sooner than boys

- girls tend to manage information overload by limiting their search by format, while boys seem to not demonstrate any consistent strategy to manage overload

- when boys are behind girls in development of basic language skills, they also have problems in conducting successful online searches

- when involved in use of computer-based instruction, girls tend to prefer collaboration, while boys seem to prefer competition

- when faced with solving online information search problems, girls tend to be open to options, while boys favor finding a single path

- girls tend to score higher on tests of ability to location information in traditional reference books

Habits of Mind

The idea of "habits of mind" matches perfectly with information fluency. According to Horace Mann, habit is a cable; we weave a thread of it each day, and at last we cannot break it. Theodore Sizer (1964) defines “habits of mind” as the willingness to use one’s mind well when no one is looking. We must develop habits of mind in our PK-12 students to provide a foundation for thoughtful inquiry. According to Lauren Resnick “the sum of one’s intelligence is the sum of the one’s habits of mind” (Habits of Mind, 2003).

In their series “Habits of Mind: A Developmental Series” Costa and Kallick (2000) define and describe 16 types of intelligent behavior that promote thoughtful learning communities. Focusing on dispositions that help people know how to behave intelligently when they don’t know an answer, their “habits of mind” approach focuses on performance under challenging condition. The guiding principles of this model can help teachers deal with data and develop strategies for making data-driven decisions.

The ideas behind the development of “habits of mind” can be found across content areas. For example, the science “habits of mind” focus on essential thinking skills serve as tools for formal and informal learning in science (Georgia Framework for Learning Mathematics and Science 2000). This idea is also prevalent in the mathematics literature. In Habits of Mind: An Organizing Principle for Mathematics Curriculum (Cuoco, et al, 1995), the importance of developing thinking strategies is emphasized. They stress that the thought processes used by mathematicians are mirrored in systems that influence every aspect of our daily lives. They state that “if we really want to empower our students for life after school, we need to prepare them to be able to use, understand, control, and modify a class of technology.” They stress the development of ways of thinking and mental habits. In Math, Science, Technology & Habits of Mind, Vuko (1998) stresses that developing ‘habits of mind’ involves dispelling past fears and changing old attitudes.

To see how this approach can be applied to teaching, go to NoodleTools - Habits of Mind. Explore the Racial Privacy example.

Intelligence and Learning

Human intelligence is associated with mental capabilities including the ability to think abstractly, reason, plan, and comprehend complex ideas. Each individual differs in their ability to think and understand.

Alfred Binet invented the first popular intelligence test in the early 1900s. The test was ultimately known as the Standford-Binet Intelligence Scale.

Over the decades, concerns have been raised about reliance on test scores. Issues include gender, cultural, racial, and class bias.

Howard Gardner concluded that individuals exhibit multiple intelligences rather than just one. He found that across school and workplace learning environments, an understanding of individual differences in intelligence can be helpful in designing effective instruction. His work began in the 1980s and continues today.

Howard Gardner concluded that individuals exhibit multiple intelligences rather than just one. He found that across school and workplace learning environments, an understanding of individual differences in intelligence can be helpful in designing effective instruction. His work began in the 1980s and continues today.

In his 1983 book called Frames of Mind, Howard Gardner of Harvard University identified seven intelligences we all possess. Because our understanding of the brain and human behavior is constantly changing, the number of intelligences is expanding. Two to three new intelligences have been added recently. Gardner stresses that we all have all the intelligences, but that no two people are exactly alike.

Originally, Gardner developed the multiple intelligences theoretical model about the psychology of the mind, rather than a practical way to address individual differences. However, by understanding a student's strengths and weaknesses in each intelligence, we can help learners become more successful. He also notes that integrating multiple intelligences into the classroom involves changing our idea about teaching and learning. It requires addressing individual differences and providing a range of activities and experiences to facilitate learning.

Let's explore an example of integrating these intelligences into your thinking about distance learning.

Verbal/Linguistic. Ask yourself: How can spoken or written word be used? The Digital Collection at the University of Washington is filled with interesting essays on Native American culture. These text-based resources might be of interest to students who are verbal/linguistic.

Logical/Mathematical. Ask yourself: How can numbers, calculation, reasoning, logic, classification, or problem solving be incorporated? Consider the Daily Math website that explores how math is used in daily life.

Visual/Spatial. Ask yourself: How can visual elements such as pictures, graphics, art, color, metaphor, maps, or visual organizers be integrated? If you're studying a historical time period, consider using photographs to generate discussion and understanding. Check out the Hooverville and Suffrage photos from the Library of Congress American Memories collection. If you're working with math, use visuals to show the concept. Consider assignments that use visual tools such as using Inspiration for animal classification.

Musical/Rhythmic. Ask yourself: How can sounds and music including tone, timbre, rhythm, or melody be used? Popular Songs in American History is a website where students can explore lyrics and listen to music from history. The Cool Math site combines music and math.

Bodily/Kinesthetic. Ask yourself: How can movement and hands-on experiences be incorporated? Consider hands-on activities across the curriculum. Check out a genetics activity that involves body characteristics and movement.

Intrapersonal. Ask yourself: How can personal feelings, thoughts, and reflections be used? Consider activities that ask students to reflect on their work using tools such as notestar. Get other journaling ideas from the 42explore on the topic of journaling.

Interpersonal. Ask yourself: How can sharing, cooperation, teaming, and collaboration be used? Look for projects with multiple perspectives that might be ripe for discussions and debates such as the topic of cloning. Check out a website containing student-produced projects.

Naturalist. Ask yourself: How can environmental elements be brought into the activity? Try a geocaching activity. Learn about how you can do geocaching with kids across content areas.

Existentialist. Ask yourself: How can "the big picture" be integrated? Get students involved with looking at big ideas and questions.

Learn more about Technology and Multiple Intelligences at Teacher Tap.

Daniel Goleman theorized that emotional intelligence should also be considered when designing learning experiences. The addition of intelligences was popularized during the 1990s.

Theories of multiple intelligences are applicable to those designing instruction related to information literacy. These skills require locating, retrieving, organizing, evaluating, and using information. Knowledge of multiple intelligence can help teachers better understand the individual differences of learners. While some students will best understand the information process through a lecture, others would benefit from a concept map or a small group discussion about the topic. Individual intelligences may also determine how learners approach the process of gathering and thinking about information.

Try It!

Try It!

Complete Tapped into Multiple Intelligences, the free, online workshop from Educational Broadcasting Corporation.

Metacognition Theory

Metacognition involves awareness and knowledge of one's own thinking including knowledge of strategy, task, and person variables (Flavell, 1979). According to Pintrich (2002), metacognition involves both metacognitive knowledge and control.

Metacognitive knowledge includes understanding general strategies that might be used for different tasks, knowledge of the conditions under which these strategies might be used, knowledge of the extent to which the strategies are effective, and knowledge of self. Metacognitive control and self-regulation are cognitive processes that learners use to monitor, control, and regulate their cognition and learning.

Pintrich (2002) has identified three types of metacognitive knowledge:

- Strategic knowledge - knowledge of general strategies for learning, thinking, and problem solving.

- Knowledge about cognitive tasks - knowledge that different tasks can be more or less difficult and may require different cognitive strategies

- Self-knowledge - knowledge of one's strengths and weaknesses

Today's information explorer faces the daunting task of selecting relevant, meaningful topics to investigate, identifying timely resources, maneuvering through data sources, evaluating the accuracy of sources, synthesizing information, and drawing conclusions with constantly changing information. Illustrating how to move from a question to relevant resources can be a powerful way to show how choices are made to accept, confirm or reject information. Annette Lamb, professor of online course development at Indiana University, shows how one teen’s information inquiry process can be illustrated (Click to enlarge the figure below). Like most teens, Jamal communicates with family members through email. When he receives an email "forward" from him grandmother in Florida, he generally puts it in the trash. She sends lots of "forwarded messages" including chain emails, prayers, political jokes, and urban legends. While she thinks of these messages as fact, Jamal is much more skeptical. He's also mature enough not to argue with grandma. However one email forward catches his eye. The headline is "The New Canine Influenza". The message indicates that a virus deadly to dogs was first found in greyhound race dogs and has been spreading in the canine population of the U.S. He wonders if this could be true. His grandmother is clearly concerned about Bailey, the family dog.

Today's information explorer faces the daunting task of selecting relevant, meaningful topics to investigate, identifying timely resources, maneuvering through data sources, evaluating the accuracy of sources, synthesizing information, and drawing conclusions with constantly changing information. Illustrating how to move from a question to relevant resources can be a powerful way to show how choices are made to accept, confirm or reject information. Annette Lamb, professor of online course development at Indiana University, shows how one teen’s information inquiry process can be illustrated (Click to enlarge the figure below). Like most teens, Jamal communicates with family members through email. When he receives an email "forward" from him grandmother in Florida, he generally puts it in the trash. She sends lots of "forwarded messages" including chain emails, prayers, political jokes, and urban legends. While she thinks of these messages as fact, Jamal is much more skeptical. He's also mature enough not to argue with grandma. However one email forward catches his eye. The headline is "The New Canine Influenza". The message indicates that a virus deadly to dogs was first found in greyhound race dogs and has been spreading in the canine population of the U.S. He wonders if this could be true. His grandmother is clearly concerned about Bailey, the family dog.

Having recently read The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the 1918 Pandemic by John M. Barry for a science class, Jamal considers whether this could be connected to other recent viruses such as the "bird flu." Like most teens, Jamal spends lots of time on the Internet. His first stop is Snopes (http://snopes.com) to look up dog flu. He quickly locates a copy of the ominous email and is shocked to find that Snopes indicates the email is True. After reading the background information found by Snopes, he decides to conduct his own investigation to confirm the information in the email.

The message refers to an article at Recombinomics.com, so he checks the reference. Wondering about the credibility of this website, he examines the Founder page and learns that the website is authored by a person with authority. To check his credentials, Jamal googles "Henry L Niman". He finds that Niman is being interviewed by many news and health organizations worldwide on this topic.

The article also mentions AVMA. Googling AVMA brings up the American Veterinary Medical Association. This website contains the JAVMA (Journal of Veterinary Medical Association) News which links to an article titled "Canine influenza virus emerges in Florida." It states "Known as canine influenza or canine flu, the disease is caused by a highly contagious virus that was recently identified by researchers at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine." Jamal decides to read the press report from the Florida Agriculture and Consumer Services Commissioner titled Bronson Alerts Public to Newly Emerging Canine Flu. The article indicates that the actual report is in the journal Science (30 September 2005). Unfortunately he doesn't have access to the journal Science, so he logs into his school library to search for the article. He finds that the current issue isn't available online, but it is available in the physical library.

Jamal goes to the journal Science online and wonders about their credibility. The copyright notice indicates the magazine is published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The AAAS website confirms that this organization is actually associated with this magazine. He has confidence in this source. The email also mentions the APHIS. He googles APHIS and learns that it's the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the USDA. The website isn't well organized, so he leaves. Finally, he checks the references provided at the Snopes website from the New York Times and Boston Herald. Satisfied that people are concerned about this topic, Jamal decides to see what government officials are doing to address this concern. Having gone to the CDC (Center for Disease Control) as part of his 1918 Pandemic report, he starts there.

Jamal reads a transcript from a news briefing held September 26, 2005. Now we're getting somewhere. The conference includes the author of the article, Dr. Crawford from the University of Florida along with people from the CDC and Cornell. The discussion conveys the idea that the flu is a concern, but that the illness has a low mortality rate. The lead researcher even indicates that she would continue to show her dogs at Kennel Club events and is confident that they'll be fine. This makes Jamal feel much better. Jamal emails his grandmother to assure her that Bailey will be fine.

To be effective in a digital world, teachers as well as students must become metacognitive explorers. The visual below represents Jamal's inquiry process. He is asked to not only create a visual journal of his experience, but also reflect on the skills and sources used during the inquiry process. When Jamal’s experience illustrated in the visual map (Figure 1 above) is matched to his key experiences and sources (Click to enlarge the figure below), it’s possible to trace Jamal’s thinking and use of resources. Notice that he begins with a meaningful question that is associated with prior knowledge and personal context. He begins his exploration with a “comfort source” that he has used successfully in the past. His experience with email-based urban legends leads him to the popular Snopes.com website. Once he has confirmed that the Canine influenza is based on fact, Jamal begins to look for linkages that will lead back to the original source. This involves backtracking to the original source of the email message and checking facts using credible sources such as a well-known organization, a government source, a peer-reviewed journal, and an authoritative agency. Finally, Jamal is able to answer his original question and create a fact-based communication back to his grandmother.

Motivation Theory

Motivation is the willingness and desire to participate or do something.

Motivation is the willingness and desire to participate or do something.

Some students find school boring. Motivation is particularly important to young adolescents who are quick to question the importance of school assignments (Lipscomb, 2003).

Intrinsic motivation comes from within a person including personal, professional and academic desires; the need to conform or succeed; or the thrill of a challenge.

Intrinsic motivation is evident when people engage in activities without outside suggestion or pressure. This motivation may come from the desire for enjoyment or a feeling of obligation. For example, some students enjoy reading graphic novels for pleasure even though they may not be on the "Accelerated Reader" book list.

Online students are more likely to be intrinsically motivated if they:

- are interested in the topic,

- see the value in course content and activities,

- believe that their energies impact whether they succeed,

- feel like they are in control of their own learning

Extrinsic motivation is driven by external forces and structures such as increases in pay for course credit and rewards for program completion.

Extrinsic motivation occurs when people take action based on tangible or intangible rewards or other outside influences. For example, teachers may entice children with stickers or promises of class parties.

Consider how you might incorporate the following elements to increase extrinsic motivation:

- Reward students who meet learning goals with good grades

- Praise students who complete activities and discussions

- Encourage students to provide kudos for their classmates

Although experts are intrinsically motivated, novice learners need guidance and encouragement. Motivation can be enhanced in novices if they use high-quality self-regulatory processes such as self-monitoring. The level of self-satisfaction increases as they see their progress (Schunk, 1983).

Motivate your online learners through ongoing encouragement, course clarity, meaningful materials, and learner engagement.

Motivate through Ongoing Encouragement

- Establish ongoing communication with your class through announcements or personal email

- Incorporate text in your course materials that convey the idea that course materials will be useful in promoting quality of life, job satisfaction, etc.

- Use humor and light-hearted approaches to increase comfort

- Remind students they're saving time by not traveling to a face-to-face class

- Ask students to enjoy the freedom of online courses

- Provide reminders about the schedule and praise students for staying on schedule

- Encourage students to establish a personal reward system

Motivate through Course Clarity

- Clearly state course requirements with emphasis on learner control over success

- Provide clear assignments and assessments

- Provide specific, quick, feedback, encouragement, and grading

- Identify specific due dates. Some students need to structure of due dates motivating.

- Be flexible enough to accommodate emergencies and specific problems

- Provide learner support through scaffolding assignments

- Encourage student questioning and sharing of concerns

Motivate through Meaningful Materials

- Place emphasis on activities that will meet course goals and aren't perceived as "busy work"

- Provide varied real-world examples

- Use authentic examples, timely resources, and real-world data that promote interest and practicality

- Provide multiple channels of communication (i.e., text, graphics, audio, video) so learners have choice in learning

- Personalize activities and build in flexibility to meet individual needs

Motivate through Learner Engagement

- Appeal to student life experiences.

- Apply course content to real-world situations

- Provide students with choices in terms of topics

- Allow students varied ways to share their understandings (i.e., text, visual, audio)

- Require ongoing participation through the course

- Incorporate interactive features that involve learners in practice, reflective thinking, and problem-solving.

Self-Regulation Theory

Whether taking a face-to-face or online course, students must be able to manage their own learning. The ability to self-regulate is critical for success.

Self-regulated learning involves:

- Motivating oneself to take action, complete assignments and stay on track

- Planning, monitoring, and evaluating personal progress during the course

- Adapting to changing personal circumstances and academic challenges

- Adjusting performance to address personal strengths and weaknesses

- Applying strategies to course demands

- Attributing successes and failures to factors oneself

- Exerting effort to learn

A key element of the human personality, Bandura (1977) defined self-regulation as the ability to control our own behavior. Self-regulation involves three steps:

A key element of the human personality, Bandura (1977) defined self-regulation as the ability to control our own behavior. Self-regulation involves three steps:

- self-observation - examining ourselves, our thinking, and our behavior

- self-judgment - comparing ourselves to a standard

- self-response - reacting to our judgment through self administered rewards and punishment

Self-regulated learning is the deliberate planning and monitoring of the cognitive and affective processes involved in completing academic tasks (Corno and Mandinach, 1983). According to Winne (1995), most effective learners are self-regulating.

Yang (1993) found that high regulatory students:

- tend to learn better under learner control than program control situations

- able to monitor, evaluate, or manage their learning effectively during learner controlled instruction with embedded questions

- reduce instructional time required to complete the lesson when they have control

- manage their learning and time efficiently

Much work has been done in the field of self-regulation by Barry J. Zimmerman a professor at the Center of the City University of New York. He states that self-regulation is the "self-directive process by which learners transform their mental abilities into academic skills." (Zimmerman, 2002)

Self-regulated learners are “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process” (Zimmerman, 1989, p. 329). To accomplish their goals, learners set personal goals, perform strategically, monitor their progress, and adapt their approach. These skills are essential for life-long learners. Whether managing a business or developing a work of art, people must be self-reliant. Zimmerman identified a number of strategies for self-regulation:

- self evaluation

- organizing and transforming

- goal-setting and planning

- seeking information

- keeping records and monitoring

- environmental structuring

- self consequating

- rehearsing and memorizing

- seeking social assistance

- reviewing records

According to Schunk and Zimmerman (1998), self-regulation is not a specific mental ability, instead it involves a series of component skills including:

- setting specific proximal goals for oneself

- adopting powerful strategies for attaining the goals

- monitoring one's performance selectively for signs of progress

- restructuring one's physical and social context to make it compatible with one's goals

- managing one's time use efficiently

- self-evaluating one's methods

- attributing causation to results

- adapting future methods.

In Becoming A Self-Regulated Learner, Zimmerman (2002) identifies how a student's use of specific learning processes, level of self-awareness, and motivational beliefs combine to produce self-regulated learners.

- Forethought Phase. This phase sets the stage for performance and involves task analysis and self-motivation. Students identify the requirements of an assignment, set goals, and plan strategies for use in their learning. For example, they may identify three questions they wish to answer and use specific Internet search strategies to locate information to address these questions. Students become self-motivated through intrinsic interest in a topic or through self-efficacy beliefs such as the expectation that answering a series of questions will lead them to a satisfying conclusion.

- Performance Phase. Self-control and self-observation are elements of the performance phase. Self-control refers to acting on the strategies outlined in the forethought phase, while self-observation involves noting and thinking about progress. The learner may also experiment with ideas. For example a student might notice that a Venn diagram works well for making comparisons and apply this technique to other aspects of a project.

- Self-reflection Phase. This phase involves self-judgment and self-reaction. Learners draw comparisons about their performance against some standard when they self-evaluate. They may also search for causes of errors and attempt to attribute their problems to particular causes. The key to self-judgment is sustaining motivation by identifying strategies that can be used to address deficiencies. Self-reaction involves how a person responds to their performance. Adaptive reactions involve students making adjustments to increase their learning by modifying a method of learning such as shifting from a brainstormed list of ideas to creation of a concept map.

By acquiring specific strategies, students can learn to take control over their thinking, behavior, and environment. As they become increasingly self-regulated, learners shift their focus from comparing themselves with others to judging their performance against their personal goals. They are also able to work independently on increasingly complex problems and projects. These characteristics are all associated with information fluency.

Students must be able to adapt to changing learning environments and self-regulate in the following areas:

- Allocation of Time - students organize their use of time and establish priorities

- Use of Information and Technology Resources - students systematically locate, evaluate, and apply resources to meet goals

- Interaction with Human Resources - students learn to effectively communicate and collaborate with others including family, peers, teachers, and community members. For example, students learn that sometimes they are more productive working individually, while in other situations it might be more efficient to ask for help.

- Selection of Physical Environment - students learn to organize their work space for maximum productivity being aware of comfort, noise, etc.

- Selection of Cognitive Strategies - students choose and apply techniques that will result in better performance

- Self-Motivation - students are aware of and control their emotions and motivational beliefs such as self-efficacy to meet their goals.

As self-regulating students work their way through the information inquiry process, they are constantly asking themselves reflective questions such as:

Forethought

- What are my needs and interests?

- What are my questions?

- What are my goals?

- How will I allocate my time?

- What are my priorities? Where should I start?

- Where should I work?

- Should I work with a friend or by myself?

Performance

- Am I making progress toward my goals? If not, what adjustments should be made to my schedule or approach?

- Are environmental elements or classmates distracting? If so, what adjustments should be made in my work environment?

- Am I unproductive or bored? If so, what adjustments can be made to self-motivate?

- Am I getting bogged down? If so, what adjustments should be made in my strategies?

- Am I stuck? If so, where should I seek help?

Self-Reflection

- Did I accomplished my goals? If not, what can I do differently next time?

- How did I use my time? How can I adjust my schedule in the future to be more productive?

- How did I react when I became bored, stuck or frustrated? What did I learn from this experience?

- Under what conditions was I most and least productive? How can I apply this knowledge to future projects?

- What strategies were most and least successful? What techniques should I use again? What areas need to be refined?

As librarians partner with teachers to develop learning experiences for children and young adults, guidance can be provided to support self-regulated learning:

- Model self-regulation

- Shift responsibility to students

- Provide choices

- Assist in goal setting

- Encourage proactive behavior and risk-taking

- Provide context-rich connections

- Link new learning to prior knowledge

- Encourage a variety of strategies

- Anticipate students questions

- Provide corrective, positive feedback

- Encourage self-evaluation

- Promote reflection

Consider ways to facilitate self-regulation in your students by encouraging metacognitive awareness, promoting time management, encouraging social interaction, and providing effective, efficient, and appealing learning materials.

Encourage Metacognitive Awareness

Help learners use metacognitive strategies to become more self-aware. In other words, encourage students to think about themselves, their learning style, their motivation, their personality and their approach to online learning.

Ask students to consider the following suggestions:

- If you're a procrastinator, accept it and set up a rigid schedule and effective rewards.

- If you're easily distracted, identify a private workspace that will facilitate learning.

- If you need quiet, noise, or music, set up your environment with those features.

- If you work best at a particular time of day, schedule your deep thinking activities for those times.

- If you have a hard time working at a computer for extended period of time, vary your work. Read the textbook in a comfortable place, read the assignment online, do some brainstorming off-line, then return to a discussion forum.

- If you are a worrier, stay calm and contact your instructor if you have trouble.

Promote Time Management

Provide learners with tips for time management during online course.

Ask students to consider the following suggestions:

- Identify the course as a priority

- Develop a regular schedule for coursework

- Keep a course calendar with study time and due dates identified

- Establish goals and deadline for yourself

- Anticipate problems (i.e., illness, technical problems) and have a backup plan for course completion

Encourage Social Interaction

To succeed in online discussions and other online course activities, participants must have basic social skills including the ability to:

- listen (read) and comprehend classmate postings

- ask appropriate questions

- assist others through supporting comments

- build on the work of others

- take on the role of devil's advocate or other perspectives to promote discussion

- synthesize information and ideas presented by classmates and make a unique contribution

- participate in a timely manner

Provide Effective, Efficient, and Appealing Learning Materials

Support learners through the design of quality course materials.

- Ensure that course materials are effective in addressing diverse learning styles

- Design materials that are time-saving and efficient

- Create appealing materials that are interesting and motivating

- Organize the course into clear, logical segments

- Review progress and forecast upcoming assignments

- Encourage students to ask questions

Situated Cognition and Learning Theory

Situated cognition refers to how people use information in daily life. It connects what a person knows with what that person does.

Situated cognition refers to how people use information in daily life. It connects what a person knows with what that person does.

Jean Lave and others developed the idea of situated learning. Lave stresses that learning is situated and is embedded within activities, contexts, and cultures. Learning is often unintentional and occurs best in authentic contexts that involves a need for knowledge.

Situated learning theory stresses social interactions and authentic learning with an emphasis on learning in the context where information will be applied in the future.

Technology can help provide virtual experiences when students such as interacting with people from different cultures.

Situated learning addresses this issue by focusing on the relationship between learning and a particular situation. Students are placed in a situation and work together to become part of the social structure. When possible, real contexts, roles, and activities are used. Examples include conducting science and social experiments in the local community. When students create products such as letters, reports, or presentation, they share these with a greater audience such as parents or peers.

Example. Many schools are requiring students to wear uniforms. What if our school board decided to vote on this important issue? Where would you stand? Your job is to identify three high-quality articles related to the topic and present these to the board to help them in decision-making. You need to defend why you chose these articles including specific evaluation criteria. Your project should also include a properly cited bibliography.

Social Learning Theory

Social learning theory involves learning through observing and modeling others. Attention, memory, and motivation all contribute to learning. The theory stresses that seeing others receive rewards or punishment can have a powerful influence on their behaviors.

Social learning theory involves learning through observing and modeling others. Attention, memory, and motivation all contribute to learning. The theory stresses that seeing others receive rewards or punishment can have a powerful influence on their behaviors.

Albert Bandura is the originator of social learning theory and the theory of self-efficacy.

Blanchett, Powis, and Webb (2012) described the four elements that make social learning effective:

- Attention - the learner needs to be paying attention and interested in learning

- Retention - the learner needs to remember and be able to apply what they learned

- Reproduction - the learner needs to be able to perform the behavior

- Motivation - the learner needs to want to perform the behavior

In teaching, apprenticeships, mentoring, and role-playing would be used. When learners see others expressing the desired behavior, they are more likely to learn that skill.

Expert vs Novice Learners

What's the difference between an information professional and a student? How does a learner evolve as an information scientist? How can librarians help students develop as information scientists?

What's an expert?

An expert has a high degree of proficiency, skill, and knowledge in a particular subject. Experts are able to effectively think about and solve information problems. They see patterns in information and are able to identify solutions. Moving from novice to expert involves much more than simply developing a set of generic skills and strategies. Experts develop extensive knowledge that impacts the way they identify problems, organize and interpret data, and formulate solutions. Their approach to reasoning and solving information problems is different than a novice.

In their report, How People Learning: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School, Bransford, Brown, and Cocking (1999) identified key principles of experts' knowledge and their potential implications for learning and instruction:

- Experts notice features and meaningful patterns of information that are not noticed by novices.

- Experts have acquired a great deal of content knowledge that is organized in ways that reflect a deep understanding of their subject matter.

- Experts' knowledge cannot be reduced to sets of isolated facts or propositions but, instead, reflects contexts of applicability: that is, the knowledge is "conditionalized" on a set of circumstances.

- Experts are able to flexibly retrieve important aspects of their knowledge with little attentional effort.

- Though experts know their disciplines thoroughly, this does not guarantee that they are able to teach others.

- Experts have varying levels of flexibility in their approach to new situations.

What are the characteristics of experts?

Early research by DeGroot (1965) found that experts perceive and understand stimulus differently from novices. He asked chess masters and beginners to think aloud as they played chess games. DeGroot hypothesized that masters would think through all the possible moves (breadth of search) and countermoves (depth of search), while beginners would not. He found that both experts and novices explored the possibilities. However the chess masters considered moves that were higher quality than beginners.

Early research by DeGroot (1965) found that experts perceive and understand stimulus differently from novices. He asked chess masters and beginners to think aloud as they played chess games. DeGroot hypothesized that masters would think through all the possible moves (breadth of search) and countermoves (depth of search), while beginners would not. He found that both experts and novices explored the possibilities. However the chess masters considered moves that were higher quality than beginners.

DeGroot concluded that knowledge acquired through experience enabled the masters to recognize meaningful chess configurations and identify the strategic implications. In other words, experts were able to see patterns and connections not evident to novices.

Much research has focused on the characteristics of experts. A few results are highlighted below:

- Glaser (1992) noted that although there is no substitute for life experiences it is possible to help students move toward thinking like math and science experts. Experts can effectively organize knowledge around key concepts, respond to context, and self-regulate their focus.

- Ericsson and Charness (1994) found that experts spend many hours each day studying and practicing. They vary their methods and explore new strategies for self-improvement. This quantity and quality in practice is reflective of expert behavior.

- Zimmerman and Risemberg (1997) found that experts plan their efforts using powerful strategies and then self-observe. For example, they might use a concept map for organizing information. They self-evaluate their performance based on their goals focusing on the effectiveness of particular strategies rather than ability attributions.

- Wineburg (1998) focused on the importance of the metacognitive aspect of expert work. When observing how historians study historical texts, he found that experts rely heavily on self-questioning and self-monitoring.

- Cleary and Zimmerman (2000) found that experts differ from novices in their ability to self-regulate. For example, experts know when to apply knowledge at crucial times during performance. Novices tend to learn reactively rather than with forethought and planning. Experts tend to set personal goals for themselves rather than comparing themselves to others.

Based on the growing body of research, the following attributes of experts can be identified. Experts:

- Pose useful questions to themselves throughout the process

- Identify relevant information and ignore irrelevant information

- Respond to context and select information to address specific needs

- Recognize meaningful patterns and connections in information

- Organize knowledge around key principles and concepts

- Self-regulate their time and efforts including goal setting, time management, self-evaluation, self-motivation

- Self-motivate through varying their methods of study and practice

- Remain flexible in thinking adapting to changing needs

What are learner-centered teaching strategies?

Although we don't expect our students to become expert information scientists, they can begin developing and applying the strategies used by professionals. According to Thompson, Licklider, and Jungst (2003), "a learner-centered approach to developing expertise requires purposeful and specific instruction that builds student capacity in these arenas". They stress that learner-centered teaching strategies should:

- contribute to the breadth and depth of content knowledge

- assist students in learning how to organize knowledge around major concepts and principles

- enhance retention and retrieval

- contribute to student development of metacognitive abilities, among other things.

Meaningful learning occurs when students are able to see the relevance of knowledge and skills and can apply these for successful problem solving. According to Mayer and Wittrock (1996) transfer is the ability to use what was learned to solve new problems, answer new questions, or facilitate learning new subject matter.

Based on our knowledge of the differences between novices and experts, how do we help student information scientists develop the necessary repertoire of knowledge and range of skills and strategies? Consider some of the following key areas:

Based on our knowledge of the differences between novices and experts, how do we help student information scientists develop the necessary repertoire of knowledge and range of skills and strategies? Consider some of the following key areas:

- Core Concepts and Experiences - learners need a foundation of knowledge, background information, examples, resources, and varied experiences related to their topic organized around the big ideas

- Task Analysis - learners must develop an understanding of the problem or key questions and be able to prioritize and focus on the key issues

- Pattern Recognition - learners must be able to structure information in meaningful ways and see the how ideas are connected

- Metacognition - learners must be aware of their thinking and flexible enough to adapt to changing needs

- Self-regulation - learners must be able to control their thinking and actions

Before working with student information scientists, it's helpful to explore your own personal growth as an inquirer. How did you mature as an information scientist?

Try It!

Try It!

Examine Annie's Inquiry and Danny's Inquiry. Reflect on your personal and professional experiences as an information scientist. Identify specific examples of how you matured as an information scientist. Predict the future of tools and techniques of information scientists. How will they change? How will they remain the same?

How do students mature as thinkers?

How do students mature as thinkers?

Like all areas of expertise, students develop knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to information science over time.

As students reflect on each experience, they gain insights that can be applied to future inquiry activities.

The key to evolving from novice to expert is building increasingly sophisticated personal tools and techniques.

According to Barbara Stripling in Curriculum Connections through the Library (2003, p. 7), "if students have not unlocked decoding skills, then specific instruction must be given to that end, but even the youngest readers can also be taught strategies to enhance their comprehension of what they are reading."

As students move through school, they develop skills in particular subject areas. For instance, Jeanne Chall identified six stages in the process of learning to read.

Listen!

Listen!

Listen to Stages of Reading to learn more about how children learn to read. Dr. Louisa Moats describe Dr. Jeanne Chall's Stages of Reading. To learn more, read the PDF.

Try It!

Try It!

Click and explore each of the following topics to explore a specific information skill and trace how a student matures as he or she gains experience and expertise. Then, create your own for another information skill.

Audience Analysis

Authority

Classics

Experts

Future Applications

Journal Your Research Experience

Linking Evidence

Key Terms and Strategies

Original Data

Question Evolution

Rating Resources

Useful Patterns

Learning Theory and Instruction

Trying to incorporate all these theories can be overwhelming. No one theory is "best" or "correct". Instead, focus on a few key ideas that bridge the various approaches.

In Learning Theories and Information Literacy, Chivers provide suggestions for developing and delivering interesting information literacy sessions:

- Provide a context for the session or course. Explain the relevance and benefits to the student for the learning

- Identify what is important for the user to learn, not for the librarian to cover in the session. Many people drive cars but do not care about how they work as long as they DO work. This is how most users feel about libraries.

- Divide the topic into small units and tasks for learning. Users who feel overwhelmed will ‘switch off’. Help them to feel they have achieved something by attending the session.

- Recognize individual learning styles and abilities and develop learning sessions to cater for individual difference. Create several formats or entry points if possible. Use demonstrations with volunteers.

- Try to make learning interesting by including some ‘surprises’. Link these to existing knowledge and then encourage them to do further research.

- Provide opportunities for practice, some in the sessions and some independently.

- Tell users what further support is available.

- Create a suitable learning environment / physical / intellectual

Rather focusing on one theory, think about a combination approaches that support quality instruction. Chickering and Gamson (1987) proposed Seven Principles based on a meta-analysis of research on undergraduate students:

-

Encourages Contact Between Students and Faculty. Frequent student-faculty contact in and out of classes is the most important factor in student motivation and involvement. Faculty concern helps students get through rough times and keep on working. Knowing a few faculty members well enhances students' intellectual commitment and encourages them to think about their own values and future plans.

-

Develops Reciprocity and Cooperation Among Students. Learning is enhanced when it is more like a team effort than a solo race. Good learning, like good work, is collaborative and social, not competitive and isolated. Working with others often increases involvement in learning. Sharing one's own ideas and responding to others' reactions sharpens thinking and deepens understanding.

-

Encourages Active Learning. Learning is not a spectator sport. Students do not learn much just by sitting in classes listening to teachers, memorizing pre-packaged assignments, and spitting out answers. They must talk about what they are learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences and apply it to their daily lives. They must make what they learn part of themselves.

-

Gives Prompt Feedback . Knowing what you know and don't know focuses learning. Students need appropriate feedback on performance to benefit from courses. When getting started, students need help in assessing existing knowledge and competence. In classes, students need frequent opportunities to perform and receive suggestions for improvement. At various points during college, and at the end, students need chances to reflect on what they have learned, what they still need to know, and how to assess themselves.

-

Emphasizes Time on Task . Time plus energy equals learning. There is no substitute for time on task. Learning to use one's time well is critical for students and professionals alike. Students need help in learning effective time management. Allocating realistic amounts of time means effective learning for students and effective teaching for faculty. How an institution defines time expectations for students, faculty, administrators, and other professional staff can establish the basis of high performance for all.

-

Communicates High Expectations . Expect more and you will get more. High expectations are important for everyone – for the poorly prepared, for those unwilling to exert themselves, and for the bright and well motivated. Expecting students to perform well becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy when teachers and institutions hold high expectations for themselves and make extra efforts.

-

Respects Diverse Talents and Ways of Learning . There are many roads to learning. People bring different talents and styles of learning to college. Brilliant students in the seminar room may be all thumbs in the lab or art studio. Students rich in hands-on experience may not do so well with theory. Students need the opportunity to show their talents and learn in ways that work for them. Then they can be pushed to learn in new ways that do not come so easily.

Resources

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall.

Benjes-Small, C., Archer, A., Tucker, K., Vassady, L., & Resor, Whicker, J. (2013). Teaching web evaluation: A cognitive development approach. Communications in Information Literacy, 7(1), 39–49.

Blanchett, Helen, Powis, Chris, & Webb, Jo (2012). A Guide to Teaching Information Literacy: 101 Practical Tips. Facet Publishing.

Bransford John D., Brown, Ann L., and Cocking, Rodney (eds.). How People Learning: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning, National Research Council, 1999.

Brown, J.S., Collins, A. & Duguid, S. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42.

Bruner, J. (1960). The Process of Education. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1964). The Course of Cognitive Growth. American Psychologist, 19, 1-55.

Callison, Daniel and Lamb, Annette (2006). Authentic learning and assessment. In D. Callison & L. Preddy, The Blue Book. Libraries Unlimited.

Chickering, A.W. & Gamson, Z.F. (1987). Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. AAHE Bulletin, 1987, 39 (7), 3-7.

Chivers, Barbara. Learning Theories and Information Literacy.

Claxton, Charles S. & Murrell, Patricia H. (1987). Learning Styles: Implications for Improving Educational Practices. Acorn.

Cleary, T., & Zimmerman, B.J. (2000). Self-regulation differences during athletic practice by experts, non-experts, and novices. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 13, 61–82.

Constructing Knowledge in the Classroom from Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL)

Corno, L., & Mandinach, E. B. (1983). The role of cognitive engagement in classroom learning and motivation. Educational Psychologist, 18(2), 1-8.

Cuoco, Al, Goldenberg, E. Paul. Mark, June (1995). Habits of mind: An organizing principle for mathematics curriculum.

Dale, Edgar (1946) Audio-visual methods in teaching. The Dryden Press.

deGroot, A. D. (1965). Thought and Choice in Chess. Mouton.

Dick, Walt, Carey, Lou, and Carey, James O. (2011). The Systematic Design of Instruction. Seventh Edition. Pearson.

Doolittle, Peter E. Multimedia Learning: Empirical Results and Practical Applications.

Ericsson, A.K., & Charness, N.. Expert performance: Its structure and acquisition. American Psychologist. 49. 1994. 725–747.

Flavell, J. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 906-911.

Gardner, Howard (1983) Frames of the Mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1991). The Unschooled Mind: How children think and how schools should teach. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, Howard, Kornhaber, Mindy L., & Wake, Warren K. (1996). Intelligence: Multiple Perspectives. Harcourt Brace.

Gardner, Howard. (1999). Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. Basic Books.

Gardner, Howard. (2004). Changing Minds: The Art and Science of Changing Our Own and Other People’s Minds. Harvard Business School Press.

Gardner, Howard (2006) Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons. Basic Books.

Glaser, R. (1992). Expert knowledge and processes of thinking. In D. Halpern (Ed.), Enhancing thinking skills in the sciences and mathematics. Erlbaum. 63-75.

Goleman, Daniel (2007). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bloomsbury.

Kolb, David A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Kovalik, Susan. Integrated Thematic Instruction.

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in Practice: Mind, mathematics, and culture in everyday life. Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1990). Situated Learning: Legitimate Periperal Participation. Cambridge University Press.

Learning Styles from Mindtools

Learning Styles & Multiple Intelligence from Vancouver Island Invisible Disability Association

Mayer, Richard E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Merrill, M.D. (1994). Instructional Design Theory. Educational Technology Publications.

Mims, Clif (2003). Authentic Learning: A Practical Introduction & Guide for Implementation. Meridian. 6(1).

Novak, Joseph D. & Canas, Alberto J. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to construct and use them. Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. Available: http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryCmaps/TheoryUnderlyingConceptMaps.htm

Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: an Investigation of the Physiological activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Dover.

Piaget, J. (1973). The Child’s Conception of the World. Paladin.

Pintrich, Paul R. (Autumn 2002). The Role of Metacognitive Knowledge in Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 220-227.

Riehle, Catherine Fraser (2012). Inciting curiosity and creating meaning: teaching information evaluation through the lens of ‘bad science’. Public Services Quarterly, 8, 227-234.

Schunk, D.H. (1983). Progress self-monitoring: Effects on children's self-efficacy and achievement.Journal of Experimental Education, 51, 89–93.

Schunk, D.H., & Zimmerman, B.J. (Eds.) (1998). Self-regulated Learning: From Teaching to Self-Reflective Practice. Guilford Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behaviour of Organisms. Appleton-Century Crofts.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285.

Teacher Tap: Brain-based (Compatible) Learning

Teacher Tap: Multiple Intelligences.

The Theory of Multiple Intelligences (MI) from EdWeb

Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal Intelligence: Experimental Studies. Macmillan.

Tilley, Carol L. & Callison, Daniel (2006). Gender. In D. Callison & L. Preddy, The Blue Book. Libraries Unlimited.

Vuko, Evelyn Porrea (1998). Math, Science, Technology & Habits of Mind. AAAS.

Wineburg, S. (1998). Reading Abraham Lincoln: An expert-expert study in the interpretation of historical texts. Cognitive Science, 22(3), 319-346.

Winne, P. H. (1995). Inherent details in self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 30, 173-187.

Yang, Y. C. (1993). The effects of self-regulatory skills and type of instructional control on learning from computer-based instruction. International Journal of Instructional Media, 20(3), 225-241.

Zimmerman, B. J. (Spring 2002). Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64-71.

Zimmerman, B.J., & Risemberg, R. (1997). Becoming a self-regulated writer: A social cognitive perspective. Contemporary. Educational Psychology, 2, 73–101.

Zimmerman, B.J., & Schunk, D.H. (Eds.). (2001). Self-regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: Theoretical Perspectives (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.