Instructional Methods

At the completion of this section, you should be able to:

- create and integrate engaging presentations into the learning environment.

- create and integrate simulations into the learning environment.

- create and integrate discussions into the learning environment.

- create and integrate games into the learning environment.

- create and integrate interactives into the learning environment.

- create and integrate practical projects into the learning environment.

- describe and apply ideas for successful instructional development.

Begin by viewing the class presentation in Vimeo. Then, read each of the sections of this page.

Explore each of the following topics on this page:

- Engaging Approaches

- Powerful Presentations

- Scenarios to Simulations

- Debates to Discussions

- Gags to Games

- Interactives

- Practical Projects

- Resources

Engaging Approaches

Although students may not express these ideas in writing, most learners want more from a course than readings and tests. They expect to be able to perform, create, and apply course knowledge and skills.

Although students may not express these ideas in writing, most learners want more from a course than readings and tests. They expect to be able to perform, create, and apply course knowledge and skills.

Ask Yourself:

How will students explore course content, become actively involved in this content, practice new learning, and share their understandings?

Instructional Approach to Inquiry

How we teach is as important as what we teach. You may have heard this phrase before, but it's true.

It might seem like planning for information literacy instruction would be easy. Simply ask students to "do it." Unfortunately, it's not that simple. Do your students know how to formulate meaningful questions? Are they able to evaluate the quality of information they see on television or read off the Internet? Can they synthesize the information they find? Do they know how to use the presentation tool you're asking them to apply? Effectively completing the information inquiry process requires a staggering amount of knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

Gunn and Miree (2012) determined that

"it is not surprising that elements of information literacy involving higher level critical thinking and discerning judgement are hard to establish in brief instructional sessions no matter what the pedagogical approach. The authors believe that more extensive research scenarios that allow students to handle the same research topic over all phases of their research can enable them to evaluate sources better. Offering opportunities for detailed engagement with texts, i.e. time to read a few publications on the same topic, can help in modelling for students how to evaluate resources. The authors will also encourage academic staff to embed steps in their assignment guidelines for research papers that encourage active evaluation in the form of annotated bibliographies or other relevant reflections." (Gunn & Miree, 2012, 32)

Achieving information fluency takes time. You can't possibly address everything students need to know within a single project. That's the purpose of integrating information inquiry competencies throughout the scope and sequence of the entire PK-20 curriculum. Although the process will remain the same, the depth and breath of the investigations will vary.

Example: Kindergartners can trace the origins of the milk on their lunch plate back to a daily cow using pictures and key words like store, truck, and farm. While a high school student might question the use of pesticide in the grain eaten by dairy cows.

Each classroom situation provides an opportunity to introduce new skills and build on existing knowledge. For example, in some situations it makes sense to have students use search engines to locate information to address questions. In others, it might be a more efficient use of time to provide three quality websites and ask students to concentrate their efforts on comparing the three different perspectives. Your choice of approach will depend on the entry skills of your students as well as the specific standard you wish to address in the inquiry. It makes sense for students to use search engines themselves if one of the outcomes relates to helping students narrow or broaden their topic.

In the chapter Empowered Learning in Curriculum Connections through the Library edited by Stripling and Hughes-Hassell, Violet H. Harada (2003, p. 54) describes the work of Wehlage et al (1996) indicating that learning environments that result in significant achievement contain the following three attributes:

- Construction of Knowledge: students have guided practice in acquiring the skills and knowledge they need in the adult world. This involves constructing rather than simply reproducing knowledge. Students 'produce original conversation and writing, repair and build physical objects, perform artistically.'

- Disciplined Inquiry: students develop an in-depth understanding of a problem rather than shallow exposure to isolated bits of information. While past knowledge is a fundamental component of learning, students are challenged to push beyond this knowledge 'through criticism, testing, and development of new paradigms.'

- Value Beyond School: student accomplishments have an impact that extends into the real world. Students wrestle with situations and issues connecting their learning with larger public problems or with personal experiences.

Research supports the idea that learner-centered classrooms enhance student learning, social, and emotional outcomes. In these environments, teachers focus on the individual differences and learning needs of children. Then develop a range of instructional activities and learning support to address these needs (Lambert & McCombs, 1998).

Marzano, Pickering, and Pollack (2001), conducted a meta-analysis of research studies on instructional strategies. They identified nine strategies to enhance student performance.

Marzano, Pickering, and Pollack (2001), conducted a meta-analysis of research studies on instructional strategies. They identified nine strategies to enhance student performance.

- Identifying similarities and differences

- Summarizing and note taking

- Reinforcing effort and providing recognition

- Homework and practice

- Nonlinguistic representations

- Cooperative learning

- Setting objectives and providing feedback

- Generating and testing hypotheses

- Cues, questions, and advanced organizers

What learner-centered strategies can be used to help students become more information fluent?

Most instructional situations include a wide range of approaches to attract and maintain the attention of learners, disseminate information, and provide opportunities for practice. Lahlafi, Ruston, and Stretton (2012) developed an active learning experience for business students learning web search skills. In Active and reflective learning initiatives to improve web searching skills of business students, Lahlafi, Ruston, and Stretton (2012) explained that a lecture hall setting was used because of the large student audience. However, the instructors looked for ways to actively engage students in meaningful activities. Examples include:

- A paired exercise connecting previously used resources with new materials.

- Group work reviewing the pros and cons of different sources.

- Analysis of a "real-world" situation presented through a video clip.

- Demonstrations illustrating the advantages and disadvantages of web resources.

- A humorous visual example.

- A website evaluation checklist and discussion of fake websites.

Gross and Latham (2011, 183) note that "instructional strategies can harness students' preference for people as sources toward instructional ends by developing programs that promote personal contact with trainers."

Limberg, Alexandersson, Lantz-Andersson, and Folkesson (2008, 82) found that

"teacher/student interaction with a focus on learning goals and content is a vital condition for students' meaningful learning. Focus on the object of teaching, away from information seeking skills toward an emphasis on the quality of students' research questions, on negotiating learning goals between pedagogues and students, and on the critical evaluation of information sources related to the knowledge contents of students' assignments improves learning."

Use engaging activities to bridge theory and practice. Student must be able to use vocabulary, apply rules, and cite principles during scenarios, discussions, and games. Build these elements into the activities:

- Terminology. Require students to label pieces of equipment or screen captures, define the words they are using, and discuss how the situation could be different.

- Rules. Ask students to journal or state the rules they are applying.

- Principles. When developing activities, incorporate elements that require students to state the principles they are applying.

Look for real-world experiences that bridge theory and practice.

Example: Try the Copyright MicroModule, Citation MicroModule, Ethical Use MicroModule, and Plagiarism Micromodule.

View Teaching and Learning Strategies (5:49).

View Teaching and Learning Strategies (5:49).

In this video, Annette Lamb discusses teaching and learning strategies, technology as tool, springboard – prior knowledge, information exploration, multimedia rich environment, drill & practice, simulations, tech tools create products – Excerpt from “Integrating Technology in the Curriculum”, Canter & Associates

Read!

Read!

Read Ostenson, Jonathan (January 2014). Reconsidering the checklist in teaching Internet source evaluation. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(1), 33-50.

Let's focus on some specific types of activities that will engage your learners and facilitate the development of specific skills.

Powerful Presentations

Think of a presentation as a performance. Before you enter the "stage," tell yourself that it's showtime! If you aren't comfortable in front of an audience, invent a "teacher persona" for yourself that's confident, motivating, and interesting.

Presentations

How you look and act plays a large role in a successful presentation.

How you look and act plays a large role in a successful presentation.

- Dress for Success. You should be dressed slightly better than your audience. In other words, people should be able to identify you as the speaker.

- Smile. You'll feel more confident if you smile. Or, at least don't frown. Put on your friendly face and be enthusiastic about your content.

- Make Eye Contact. Smile and make eye contact with your students. Before the class or presentation, walk around and introduce yourself to individuals and small groups. Make students feel comfortable.

- Stand Up Straight. Don't slump. Be confidence. Stand up straight. Although some speakers like to sit behind their computer, resist this urge. Instead, request a podium where you can place your laptop and a high table for materials. If you must sit, use a tall stood so you can still make eye contact with your students.

- Move Around. Rather than standing in one place, move around the room. You don't need to be in constant motion. However motion added interest for the audience. Place props around the room, refer to the screen with a laser pointer, or simply move around from behind the podium. Avoid repeated motions such as fiddling with the remote control or rocking back and forth. These can be distracting. Also consider cultural gestures that can be confusing or offensive.

- Use Humor. A positive attitude is an important part of speaking. Jokes, comics, and other forms of humor can break the ice, introduce an idea, or jumpstart discussion. However be sure that the humor tied directly with the instruction. Avoid sarcasm and be culturally sensitive. Self-deprecating humor is most effective because it makes you more accessible to the audience.

- Stop Disruptions. Whether you're dealing with children or adults, you may run into discipline problems. Confront problems head-on. Do not tolerate rude behavior such as cell phone calls or back chatting or they will just become worse. If a cell phone rings, remind people to turn off phones. If chatting in the back of the room is a problem, physically move toward the back of the room to make the people aware that you're listening. Or, ask if they have a question. Or, during a small group activity talk to the individuals privately. Try to stay positive.

- Interact. Students of all ages have short attention spans. You need to engage your audience every few minutes to maintain their attention. Incorporate questioning into your presentation. Ask students to react to a photograph, video, or quote. Direct them to talk with their neighbor about an issue or brainstorm ideas. The key is keeping students mentally active without disrupting the follow of your content presentation.

- Speak to the Audience. Whenever possible, face the audience. Make eye contact with different areas of the room as you speak. It's fine to write on the board or a pick of flip chart paper. However don't spend your time looking at the screen. Instead, face the audience. This is the advantage of using a podium with a computer. You can look over the screen to see your audience.

- Be Passionate. Share your enthusiasm, it's contagious.

You may not like seeing yourself on video, but it can be very useful.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to the online workshop Presentations that Pop!

Work your way this this online workshop.

Read!

Read!

Read Lecturing from Vanderbilt Center for Teaching.

Think of the skills needed for an effective lecturer. Do you have this skills? If not? How can you develop them?

Demonstrations

From showing how to use an electronic database to demonstrating the proper way to scan a historical photo, presentations related to information inquiry often have demonstration elements.

From showing how to use an electronic database to demonstrating the proper way to scan a historical photo, presentations related to information inquiry often have demonstration elements.

Consider some of the following elements for a successful demonstration:

- Pre-plan!. Whether it's a Google search or photocopy demonstration, plan ahead. Your key words should be ready to go, your websites bookmarked, and your sample photos ready to be scanned. Think about your audience and what examples they would be likely to enjoy.

- Practice. Practice the procedures, processes and approaches ahead of time. Think about what you'll say at each point. Talk your way through the process verbally. This helps students see what an "expert" is thinking as they work their way through an example.

- Focus. It's easy for new users to become overwhelmed by options, features, and choices. Focus your demonstration on the key features. If possible, put these in an easy to remember list.

- Involve the Audience. Although you want to pre-plan your activities, incorporate flexibility be involving your audience. Ask them to brainstorm words in small groups and share them with the group. Record these on the board. If you did your homework, you already know the words they will brainstorm and you'll be ready with a sample search to demonstrate.

- Scaffold Learning. Provide anticipation guides, sample searches, step-by-step instructions, best practices lists, and other handouts and resources to help students in the learning process.

- Show Troubleshooting. Rather than showing the perfect search or best example, include messy examples that require real-world problem-solving. Begin with a simple example to show the process. Then, show what happens when a problem is encountered. Discuss the problem and possible solutions.

- Plan for Disaster. Have a backup plan. If the Internet is down or very slow, you should be able to use screen-shots within your presentation.

- Plan for the Future. Not everyone may be able to attend a live event, consider using a screencasting tool and recording searches. Or, video record your equipment demonstration.

Expert Interaction

Interacting with outside experts can help learners connect course content to real-world experiences.

Professionals as Experts

Invite professionals in the field of study to interact with your students.

Invite professionals in the field of study to interact with your students.

Identify Experts. How are experts identified?

- Contact professional friends and colleagues

- Involve members from professional associations and organizations

- Contact local members of the community. Contact your local Chamber of Commerce.

- Solicit participation from government agencies. As public servants, they are often willing to participate. Locate addresses at USA.gov (Find Government Agencies).

Explore Options. How will the expert be involved with your class?

- Interact with an expert in a live real-time chat, audio, or video conference

- Involve an expert for a period of time (i.e., 3 days to 1 week) answering questions posed by students using a forum or blog

- Example: Bridging Theory and Practice

- Post information and resources by the individual with no live interaction

Prepare Students. How will you prepare your students for interaction?

- Clarify the purpose of the expert interaction

- Provide background information about the expert

- Focus the discussion on a specific topic or provide areas of expertise to help learners focus questions

- Provide examples of questions for prior semesters as examples

- Provide ideas for quality questions such as open-ended questions, questions asking for examples, questions involving situations

- Preparing students for expert interactions

Prepare the Expert. How will you prepare your expert?

- Provide background information about the students, their experiences, and learning needs.

- Place emphasis on the important of bridging theory and practice.

- Ask for specific examples and situations

Nurture Connections. How do you establish and maintain a group of experts?

- Be sure not to overuse experts by rotating people from semester to semester

- Make the activity easy by restricting the commitment to a few days

- Use technology that won't overwhelm the expert

- Provide the expert with choice of technology such as email interview vs live interview

- Reward experts with thanks, gifts, or honorarium

Share Experiences. How do you extend the experience?

- Conduct interviews and post content on the web (i.e., text/audio/video)

- Edit the interview or discussion for dissemination

- Incorporate excerpts into course materials

- Example: Words of Wisdom (Scroll to bottom of page)

- Example: Words of Wisdom (Scroll to bottom of page)

- Example: Words of Wisdom (Scroll to bottom of page)

- Example: Words of Wisdom (Scroll down page)

- Example: Words of Wisdom (Scroll to bottom of page)

If live interactions aren't possible, consider recorded interviews along with readings. Explore the Interview Index at The Lives of Teachers as an example.

Learn more at Collaboration: Ask-An-Expert from Teacher Tap

Students as Experts

As your students become more familiar with course content, get them involved with sharing their understandings with classmates.

As your students become more familiar with course content, get them involved with sharing their understandings with classmates.

Highlights. Rather than everyone doing everything, ask students to summarize the key points of a unit or discussions. Students might be responsible for 1 topic during the semester. Although this may be in paragraph form, you can also ask for:

- a 30 second podcast of the key ideas

- a top 10 list to remember

- a concept map or other visual representation of the key ideas

- a glossary

- a study guide with key points

- a voicethread audio/slideshow of key ideas

Student Bloggers. Involve students in providing examples and sample problems.

- Example: The Scribe List from Applied Math 40S

To find more examples, do a Google search for your topic and add the word "experts".

Scenarios to Simulations

Situated learning places students as close as possible to a real-world situation. When possible, real contexts, roles, and tools are used. When a student connects what is learned to an actual situation, the translation of content becomes clear. The closer to real-life, the more effective:

Situated learning places students as close as possible to a real-world situation. When possible, real contexts, roles, and tools are used. When a student connects what is learned to an actual situation, the translation of content becomes clear. The closer to real-life, the more effective:

- Information Literacy Topics

- Compare real and fake websites

- Connect to curriculum-related topics and assignments

- Medical Topics

- Use real-situations from the news

- Use real-911 audio recordings

- Use real-“cop shop” articles

- Use real photographs

Key to Success

Successful examples, scenarios, case studies, dilemmas, simulations and role playing activities help students connect prior knowledge to new situations and contexts.

- Designed to be simple, yet complex enough to feel authentic.

- They should be close to real-life.

- Incorporate photos, documents, sounds, and data.

- Consider common mistakes and misconceptions.

Examples and Nonexamples

Examples and non-examples are important because they help students learn defined concepts. Individual instances are used to help students distinguish characteristics and classify elements of a concept.

Examples and non-examples are important because they help students learn defined concepts. Individual instances are used to help students distinguish characteristics and classify elements of a concept.

Example: Provide a situation that helps define a term. State the term.

Example: Zach set up a YouTube account using his teacher's name and personal information. He sent a text message to his teacher threatening to post a video showing the teacher smoking pot unless his grade is changed to an A. This is an example of fraud.

Example: Taylor posts on Facebook that his teacher is gay even though he's not sure if it's true. This is not fraud. It’s a non-example of fraud that can be used for comparison.For lots of examples, go to the Decision-making Process handout. It provides guiding questions and examples related to the use of social technology.

Show examples, then ask students to create their own.

Scenarios

Scenarios are descriptions of situations that provide a context for discussion or debate. They help students visualize a series of actions and can be used to test out ideas and strategies. Unfortunately, they can also be overly simplistic leading to inappropriate generalizations.

Example: Students are presented with information necessary to take on a role or solve a problem. For instance, Susan observes BLANK. She does BLANK because …. Do you agree or disagree with her reasoning? Why?

Example: Susan notices that Ben left his computer without logging off. She opens his email and sends embarrassing messages to his friends. She thinks it's okay because "he didn't log off and it's a free country." Do you agree or disagree with her reasoning?

Building Scenarios. First, design a set of circumstances including characters, setting, and action/events. Then, ask students to do one of the following:

- solve a problem

- discuss the options

- identify different perspectives

- bring the group to consensus

- respond to the situation

- identify a plan of action

- describe the steps in coming to a decision

- list the pros and cons

- convince others

Example: Students are given sample searches and must identify the problem.

Example: Students are given instrument readouts and patient information. Students must identify the problem.

Example: Visit Survival Scenario Exercise, a group dynamics team building exercise, and examine the various scenarios that are included.

Rather than simply providing text-based scenarios, begin with images, audio, or video.

Example: Incorporate short videos with background information for the scenario.

Example: Watch a news program on cyberbullying and discuss the topic.

Case Studies

Case Studies are in-depth examinations of specific situations.

Case Studies are in-depth examinations of specific situations.

The case study approach involves students in analyzing real or fictional cases in detail. While they are useful in exploring complex situations, they can be time-consuming to prepare and may not meet the spectrum of needs.

A great way to bridge theory and practice, case studies are a practical approach to help students practice course content. You're also able to see how learners apply information and demonstrate understandings in authentic situations. However ask yourself whether a case study is needed or if a scenario work as well.

Building Case Studies. Present a specific situation or set of facts. Ask students to analyze the case:

- What's the context, key characters, and setting(s)?

- How does this case relate to course content?

- What are the primary issues?

- What are the different perspectives?

- What are possible solutions, alternative approaches, and consequences of various paths?

- What are the pros and cons for each approach or solution?

- What would you do? Take a stand. Use evidence to justify the position.

- How does this case generalize to the "real world"?

Example: Rebecca is BLANK age, with a BLANK history, in a BLANK situation. How could you treat her or react to her?

Example: Rebecca is twelve and a seventh grader at Richmond Middle School... She has a computer with Internet access in her room and knows her parents keep track of her use... She isn't allowed to have a cell phone at school, but she hides it in her pocket… She lied about her age to get a Facebook account… In which situations is Rebecca acting responsibly and irresponsibly?

Ideas for Case Studies. Consider some the following ideas:

- Present a specific situation or set of facts

- Use organization websites, online reports, financial documents, or mission statements

- Analyze, forecast, create a report for, build an advertising campaign for

- Explain the rise and fall of a company

- Create a plan for this company to become more green

- Apply principles or rules from readings

- Practice client interactions and interview skills

- Ask "what if" questions

Case Studies and Critical Thinking. Encourage students to be critical thinkers who:

- Seek multiple options and solutions

- Keep an open mind

- Look at multiple perspectives

- View the spectrum of options from one extreme to another

- Look for holes in assumptions and generalizations

- Evaluate evidence

- Make informed decisions

Dilemmas

Dilemmas are situations where multiple options are provided, but none are acceptable. For instance, a dilemma may address two moral principles that required different courses of action. When students are asked to determine and justify a course of action, they learn to act on principles of justice and fairness rather than on self-interests or social norms.

Dilemmas are situations where multiple options are provided, but none are acceptable. For instance, a dilemma may address two moral principles that required different courses of action. When students are asked to determine and justify a course of action, they learn to act on principles of justice and fairness rather than on self-interests or social norms.

Students need to be aware that there may be many conflicting opinions. This approach can be overwhelming for some students, however it is effective and essential at addressing the core issues.

Example: This happened, but this happened. I’m supposed to BLANK. What should I do?

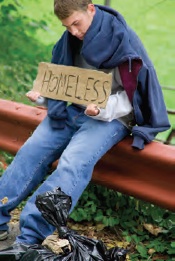

Example: In my social issues class, our team has been documenting the increase in homelessness in our community through photographs. While going through the digital photos team members took of homeless people, I realized many photos included a student from our school. I'm supposed to upload our photos to Flickr before class today. What should I do?

Simulations

Simulations involve people playing roles with real-world equipment. Use this approach to introduce a learning outcome, review materials, or provide a culminating experience. The scenario can be stopped to point out key ideas.

Simulations help students apply their skills to "real life" situations by providing an environment to manipulate variables, examine relationships, and make decisions. This type of assignment is generally used after initial instruction as part of application, review, or remediation. In most cases, simulations should be used as a culminating activity after students have basic skills in the concepts being addressed in the software. Otherwise it is difficult for them to make informed decisions during the program. Without background skills, the simulation may become an unproductive game rather than a meaningful learning experience.

Types of Simulations. There are many types of simulations.

- Physical simulations involve students in using objects or equipment.

- Procedural simulations involve a series of actions or steps such as medical diagnosis.

- Situational simulations involve critical incidents within particular settings such as interactions with patients.

- Process simulations involve decision making skills related to topics where students must choose among alternative paths.

Building simulation. Invent roles (i.e., patient, responding crew, bystanders, and facilitator. Provide cards for each role. Incorporate at least one of the following:

- Location. Consider a location such as the bathroom, hall, bottom of stairs to add realism.

- Noise. Incorporate background noise to add to realism

- Makeup. Use realistic wound makeup.

- Props. Use pill bottles, medical alert tags, dishes, food wrappers, medical supplies, newspapers, and other products.

Make it Real

- Setup

- Provide all necessary equipment

- Use standardized skills sheets

- Allow guided practice skills prior to scenario

- Check skill competence before running scenario

- Add realism (i.e., props, noise, makeup)

- Assign Roles

- Evaluator: Uses skills sheet and records steps performed.

- Information Provider. Uses a script and provides information.

- Team Leader: Primary Patient Care Provider or Librarian

- Partner: Performs care as directed by leader

- Patient: Faithfully portrays signs and symptoms according to scenario

- Bystander: Acts as distractor or helper

- Run Scenario

- Distribute the script

- Use real calls and primary source data such as forms

- Begin by reading the dispatch information

- Do not interrupt the scenario unless someone is in danger

- Evaluate

- Use Positive-Negative-Positive format

- Start with positive statements

- Provide constructive feedback and areas for improvement

- End with positive reinforcement

- Allow role players to comment

- Rotate Roles for Next Round

Adapting Simulations. When selecting simulations consider the amount of time you have to dedicate to the program. Some simulations can be time-consuming if done well. Also consider the grouping of students. Ask yourself:

- Will students complete the simulation as individuals, in small groups, or as a class?

- Does the simulation support the activities you are doing in the rest of your unit? In other words, does the simulation match your vocabulary and instructional approach?

- Is the content realistic enough to involve the students?

- Will they really "get into" the simulation or simply treat it like a game? For example, does it make a difference that the students aren't responsible for real money or lives.

Creating Simulations. Explore the following ideas for creating simulations:

- Recreate a situation

- Provide materials for preparation

- Provide guidelines for the simulated event

- Establish a learning space for the exchange

- Establish a time frame for the exchange

Role-Playing

Role-Playing allow students to practice what is being taught in a controlled setting. Participants in role playing assignments adopt and act out the role of characters in particular situations.

Role-Playing allow students to practice what is being taught in a controlled setting. Participants in role playing assignments adopt and act out the role of characters in particular situations.

What role could the person in the photo be playing?

They may take on the personalities, motivation, backgrounds, mannerisms, and behaviors of people different from themselves. Set the stage and provide handouts or sheets with key information. Debrief at the end to reinforce learning objectives. (NAEMS, 2006)

- Student-student scripted role play

- Student-directed improvisational role play

- Instructor-student role play

- Guest role play

Role-Playing Activities. Consider the following activities that involve role-playing.

Conversations and Interviews. Role-playing conversations is a wonderful way to practice foreign language skills, try out parent/child interactions, or conduct mock interviews. Ask students to take the perspective of a member of an organization (i.e., company, school, non-profit).

Debate. Students might be asked to take one of two positions or perspectives in a debate situation. In an online environment, the debate could take place live through chat, audio, or video conference. Working in pairs, students could create a collaborative presentation following the debate format. Each student would create every other slide.

Explore an example at Rhetoric.

Demonstrations. Students might audio or videotape themselves performing a task.

Improvisation. In an improvised situation, students play the role of their character in a free-flow environment. For instance, individuals might take on the role of a past President sitting at a take of other past Presidents. What might they say to each other?

Historical Re-enactments. Using an avatar in Second Life or describing their character in text, learners can design a virtual environment for historical re-enactments.

Mock Trial. Students take on a role related to a trial situation. The trial is acted out through an online discussion.

Response Preparation. Students might take on the role of a first responder and act out the steps they would take in a particular situation.

Outside Evaluator. Students may be asked to act as an "outside evaluator" or "consultant" on a particular topic.

Creating Role-Playing Assignments. Think about the the activities of the instructor and student in a role-playing situation.

The instructor would set up the role-playing situation by:

- providing materials for role preparation

- providing guidelines for the simulated event

- setting up the situation for the exchange

- establishing a learning space (i.e., forum, wiki) for the exchange

- establishing a time frame for the exchange

- identifying background information about the character

- associating the character particular behaviors

- creating an outline, a concept map, or notes to be using during the role playing event

- contributing to the role-playing learning space for a specified period of time

Try It: I'm Fine. Just Give me a Band-Aid Role-play

Try It: I'm Fine. Just Give me a Band-Aid Role-play

Step 1: Divide the group in half. Move to opposite sides of the room.

Step 2: Members of Group A will take on the role of a reluctant patient and brainstorm a set of provocative statements, questions, or demands.

Example: “I’m late for a meeting and I don’t have time for this.”

Step 3: Members of Group B will take on the role of EMTs and brainstorm effective statements to defuse the situation and empathic reactions to provocative statements.

Example: “Sir, I’m sorry you feel that way. We can save time by….”

Step 4: Identify a member of the opposite team and conduct a one-on-one conversation between the patient and the EMT. A member of Group A will initiate the angry conversation by asking a question or making a demand. The person from Group B will respond in a calm and empathetic fashion to defuse the hostility. After one minute, the pairs will shift.

Step 4: Identify a member of the opposite team and conduct a one-on-one conversation between the patient and the EMT. A member of Group A will initiate the angry conversation by asking a question or making a demand. The person from Group B will respond in a calm and empathetic fashion to defuse the hostility. After one minute, the pairs will shift.

Step 5: After all Group A members have interacted with Group B members, take a couple minutes to create a character and switch roles. Conduct another set of rounds.

Step 6: Debrief.

What are techniques and statements that worked effectively to defuse or calm the patient?

What are examples of empathic, apologetic, reassuring, and limit-setting statements?

What is a piece of advice you’d give a new EMT?

Step 7: Discuss the use of role-playing as a teaching tool and design your own assignment.

Step 8: If you have time, try a round focusing on your own role-playing assignment.

Redesign the "Just Give Me a Band-Aid" Role-play into a "Just Give Me Google" Role-play.

Try It: Simulations

Try It: Simulations

Compare examples, scenarios, case studies, dilemmas, simulations, and role

playing activities.

How are they alike and different?

Select and think about one of these techniques and how you use it.

Discussions to Debates

Discussions are a way for students to share their understanding of course content. A debate is a type of formal discussion on a particular topic where opposing arguments are presented.

Discussions are a way for students to share their understanding of course content. A debate is a type of formal discussion on a particular topic where opposing arguments are presented.

Class discussions are one of the most popular activities in online courses, book clubs, seminars, and conferences. However without careful planning, they can bore participants and be viewed a "busy" work rather than meaningful learning experiences.

Forums can range from free-flow sharing of ideas to highly structured activities. However it's important to identify the specific purpose of the discussion and design assignments and assessment that reflect this need. To accomplish the course goals, it's also necessary for the instructor to carefully monitor and manage the discussions.

Technology for Online Discussions

There are many online tools for coordinating online discussions.

First, consider whether an existing service might be used. For instance, if you're developing an online book club, you might use an existing service such as LibraryThing or setup group at Goodreads as the forum tool for your discussions.

Second, use an online service that specializes in groups and forums such as Google Groups or Yahoo Groups.

Third, if you want to do more than simply hold a discussion, consider a course management tool for nonprofits such as NiceNet. Or, a social network builder such as Ning.

Fourth, if you have access to your own web server consider a open source software such as the course management system Moodle or the forum tool phpBB.

The Cs of Discussions

Be sure that your discussions are part of the larger learning experience. Consider the C's of Discussions:

- Community. Set up a positive atmosphere for discussion. Encourage risk-taking, value multiple perspectives, and promote peer feedback and support.

- Content. Provide a shared experience such as a chapter, article, video, photo, scenario, or other materials to serve as background information. Encourage students to cite sources and provide examples rather than simply offering opinions.

- Context. Present students with a problem, situation, or scenario for the discussion. You might cite the shared experience and present a question or dilemma.

- Create and Contribute. Rather than simply posting a comment, ask students to create something that will extend the discussion. They may share an example, provide a critique, or pose a solution.

- Collaborate, Conflict and Compromise. After making an initial contribution, ask students to take action based on the ideas generated in the discussion. They might collaborate, address a conflict or reach a compromise.

- Culminate. Bring all the ideas together in a final statement of conclusion.

The Purpose of Discussion

Before designing discussion assignments, ask yourself: What's the purpose of the discussion activity?

Forum assignments provide an environment where information and ideas can be shared and discussed. Start by examining your course goals and objectives.

Will a discussion help students:

- build a sense of community?

- explore course content?

- extend a course reading experience?

- share an experience or example that demonstrates understanding of course content?

- peer problem-solve?

- model course concepts?

- demonstrate a skill?

- practice a skill?

- collaborate to create a product that reflects course content?

- set goals or plan for a project?

- review the work of a peer?

Identify the goal of the experience:

- What will the student posting a message get out of the experience?

- What will the student reading a message get out of the experience?

- What will the student replying to a message posted by another student get out of the experience?

- What's the motivation for participation?

Try It!

Try It!

Examine book discussion programs that could be adapted as online programs. How could you promote high level thinking in these discussions?

GoodReads Groups

One Book reading promotion projects from the Library of Congress

Book Group Buzz from Booklist (ALA)

Center for the Book from Library of Congress

As you begin designing assignments, think about ways to associate discussions with course materials. Students could be asked to

- cite readings from inside and outside the course materials

- associate a personal experience with course content

- identify or invent an example or problem

Course Discussion: Relevance

Once you've identified specific learning objectives, focus on specific activities that stimulate critical and creative thinking. Consider the purpose of each discussion before writing discussion questions. Also keep in mind that the educational outcomes must be clear to the students.

Students particularly enjoy discussions that involve real-world situations, authentic resources, and practical experiences.

Use the following ideas to help you build meaningful, relevant discussions:

Activate. Motivate learners. Use discussion as a catalyst to generate interest in a new topic. Help students see the excitement and energy that can be found in a subject. For example, show the enthusiasm of mathematicians.

Communicate. Use connections to course content to share ideas, personal perspectives, or shared experiences.

Connect. Provide a context or establish a connection. Bring relevance to the discussion by using a "real world" situation or example.

Critique. Critically evaluate an idea or perspective by using examples to support a position. Many of these examples can be found in professional blogs.

Deepen. Add depth to a learning situation by providing a detailed explanation, thoughtful observation, or new resource that provides additional information or insights. For example, use a law blog to learn more about law and ethics or use an author blog to explore issues in creative writing.

Evidence. Provide resources that students might use as evidence in justifying a perspective, solving a problem, or making a decision.

Expand. Broaden thinking by providing an alternative perspective or different point of view. For example, use readings from different countries to examine cultural differences.

Fresh Look. Use discussion starters to provide current, immediately relevant examples. For example, get the latest science or fashion news.

Inform. Provide primary sources or data that help explain an idea already presented. For example, you can track earthquakes and volcanoes. Consider a statistic or graph that illustrates a point.

Inference. Involve students in resources that can be used to facilitate problem solving and inference.

Launch. Use focal points as a place for stimulating new, innovative ideas. Be the first to present a new idea rather than simply commenting on the work of others. Ask questions to keep the new idea going.

Organize. You may provide resources you wish student to organize. They may categorize, sequence, or create a hierarchy.

Storytell. Involve learners in telling or retelling a story. They may be providing narration, reviewing the steps in a process, or describing events.

Synthesize. Bring a number of ideas together. For example, consolidate these comments and draw a new conclusion.

Teaching. Involve learners in teaching others through demonstrations, mentoring, or sharing course content.

Course discussions are more meaningful when placed in a context. Identify focal points that can serve as a shared experience and provide a context for learning. The focal point may be content that you identify such as a required reading or a set of photographs to examine. It may also be something selected by a student such as an article they have identified or a poem they have written.

Seek out materials that will engage learners. Also look for materials that address different learning styles or intelligences.

Establish a Context for Discussion

Identify discussion focal points that can be used as the basis for questioning, problem-solving, and decision-making activities. This list can also serve as a place to look for examples or real-world applications of course content.

Artwork. Pieces of artwork can convey emotion, reflect a time period, or inspire creative writing.

- Use the Art History Resources on the Web for ideas.

Audio program or podcast. Although you or your students may choose an entire program for discussion, you may also select a quote from a speech or an excerpt from a podcast as a focal point.

- Explore the following podcasts for science ideas: Earth and Sky, Science Update

- Explore popular radio shows for ideas: NPR

Blog postings. Blogs generally focus on current events and often provide commentary or personal insights. Select or ask students to select a book review, political viewpoint, or piece of commentary as the focus of discussion.

- Do a Google Blog Search for resources.

Data Sources. Census data, drug use statistics, and sporting event numbers could all be used in social studies or science discussion, writing exercises, or mathematics problems.

Graphics. Seek out charts, diagrams, illustration, maps, organizers, photographs, cartoons, symbol. Use photographs found on the web or those taken by you and your students.

- Cagle's Professional Cartoonist Index

- Put yourself into the place of a character from the novel. Create a diagram showing the relationships between your character and the other characters in the novel.

Examine the photograph on the right. Consider the following questions:

Examine the photograph on the right. Consider the following questions:

- Who placed these flags?

- What does this image mean to you?

- Where could this photo have been taken?

- When was it taken?

- Why do you think these flags were placed here?

- How long have the flags been waving?

- Who else as seen these flags?

- What words come to mind?

- What have these flags seen in their lifetime?

If you're interested, we took the photo above outside a pioneer cemetery in southern Utah.

Interactives. Although interactives can be used for practice, they can also serve as the focal point for discussion. For example, you might ask students to critique the accuracy of an interactive or suggest additional elements could added to an online game.

Interviews. Ask learners to read, watch, or listen to an interview or conduct their own interview.

Literature. A chapter from a novel, an excerpt from a short story, or a poem can all serve as effective focal points.

Periodical article. Print journals, online magazines, and newspaper articles can all serve as effective discussion starters. Seek out current events: Arts & Letters Daily, Science Daily, SciTech Daily

Primary source materials. Historical documents, treaties, certificates, posters, and other original materials can bring people, places, and events to life. Use them to inspire creative writing, stimulate thinking, or pose math problems.

Examine the photograph above. Consider the following questions:

- What would it have been like to be a young woman with two small children living in rural Iowa in the 1910s?

- How would her life have been different than someone living somewhere else in the US or the world at the same time?

- How would her life be like and unlike a person today?

If you're interested, this is a photo of Annette Lamb's great grandmother Hazel Bolger taken in 1916.

Textbook or course reading. Course readings can be overwhelming causing key ideas to be lost in the ocean of information. Use course discussions as a way to focus on essential elements of the readings.

Video program. From the Library of Congress and PBS to SchoolTube and YouTube, a wealth of video is available online. It's not always necessary to view an entire program.

Wiki articles. Like all resources, it's important that learners carefully evaluate what they read. A wiki is an opportunity to read and critique the work of others. It's also possible modify, expand, and enhance the work of others. For instance, ask learners to read a particular article and expand the references or identify fact vs opinion. For ideas, explore Wikipedia.

Course Discussion: Prompts

Actively engage learners by reaching outside the required textbook readings and standard course content. Bring in multiple perspectives, authentic resources, and real-world problems. Also think about multiple channels of communication. Students may listen to a speech, analyze a political cartoon, or examine government data.

Example. Students are asked to watch a panel discussion titled "Academic Freedom in an Age of Industry Collaboration: A Panel Discussion" (length 1:35:23) at University of California Television (UCTV10). They will then continue the panel discussion online taking on the role of a fictional faculty member or industry representative discussing the key issues.

Students might be asked to

- read and comprehend course content

- analyze and interpret course content

- use and apply course content

- design and create their own meaningful example

Create a clear, concise prompt that will initiate discussion. The following discussion starters are simple examples to help you generate ideas.

Start with a(n)...

Action. Use verbs to bring a posting alive. Start with an event, disaster, or other activity. Then ask a question.

Example. Compare the number of injuries and/or deaths to similar disasters. How are they alike and different? Speculate on why.

Announcement. Make an announcement or statement. Use this to grab interest.

Example. Deaths due to BLANK are on the rise. Why?

Challenge. Challenge participants with a bold statement that might cause controversy such as one side of an argument or an opinion. Look for the controversy.

Example. State your perspective and support it with evidence.

Choice. Present options or choices then ask a question such as Which do you like best? Why?

Current Event. Present a news item or important local or global event.

Example. Create a problem based on a current event or local news

Definition. Provide a word and/or definition. Or, just a word and ask for a definition, illustration or example. Be sure to cite the source. Ask a question that requires a definition.

- Example. Let's create a visual glossary! Share an image that helps to visualize a concept from the Chapter 5 glossary. Share the word, definition, and image. Then explain how the image represents the word.

Emotion or Feeling. Talk about a feeling or emotion related to a particular situation.

Example. How do you react in stressful situations? Why? What can you do to handle stress?

Experience. Focus on personal or professional experiences and examples. Connect it to the discussion or topic. If possible, incorporate visuals such as photographs.

- Example. Share a personal experience or story about yourself.

Opinion. Start with an opinion and take a stand.

- Example. Provide a statement and ask students whether they agree or disagree with this statement. Ask them to provide three reasons to support their opinion.

Quote. Start with a quote. The quote could be from a famous person, book, news article, or interview. Be sure to use quotation marks and credit the source.

Question. Focus on questions about a topic (i.e., main idea, connection to other learning), book or movie (i.e., character, plot, setting), or problem.

- Example. After reading about survival in the wilderness, think about your own life and skills. Are you prepared to survive in the wilderness? Why or why not? Provide some specific examples.

- Example. Are you at risk? What about your family members? What's the risk factor associated with particular diseases? Share the risk factors associated with a particular disease and share the potential of three people you know personally.

Riddle or Puzzle. Pose a riddle or puzzle, then provide a reading to help solve the problem. Or, get students involved with writing their own riddles or creating puzzles.

Scenario. Ask readers to imagine a situation. Consider starting with dialog or conversation.

Statistic. How many or how much? Present a shocking statistic or one that people might question. Consider presenting this information in the form of a chart or graphic. Ask students to analyze this data.

Surprise. Begin with a shocking or amazing piece of information.

Course Discussion: Participation

I can't think of anything to say.

Some students find course discussions difficult. Discussions can serve many purposes. Unfortunately, they rarely reach their goal without clear guidelines for student participation. Participants need to be aware of the purpose of the discussion and their role in making the discussion a success.

While some students find online discussions easy, others are easily frustrated. Provide students with suggestions that will help them become successful participants.

Below are helpful hints for students:

- If you're unsure about the assignment, be sure to ask questions.

- If you get behind or anticipate a problem, be sure to check with the instructor early.

- Practice netiquette. Be polite and respectful of others.

- Encourage your classmates.

- Provide weblinks that contribute to the discussion and make your links hot.

- Make it clear what's fact and what's opinion. If you state an opinion, support it with an example or persuasive argument.

- Don't assume the students have read all the postings. When referring to an earlier posting, you may wish to restate the problem or quote a posting.

- Cite sources to support your views.

- Review your post for spelling and grammar errors.

- Show respect for your classmates.

- Re-read the instructions for the activity before you submit your posting.

- Re-read your message before you press "SEND".

Some students need starters for their comments. Here are some ideas:

- Your statement is important because...

- You made me wonder about...

- Your statements reminded me of...

- Your statements supported my opinion that...

- I disagree with your statements because....

- I'm confused by your statement that...

- I relate your statements to...

- An example to support your statement is that...

- The pros and cons of this approach are...

- This discussion brings up an important question...

- Based on the proceeding arguments, I conclude...

Encourage Probing Questions

Students may need help generating quality questions for their peers. Teach students to ask probing questions.

The following list can help you and your students extend the conversation through questioning:

- Assumptions. What assumptions are you making? Are you assuming... If so, ...? Can you justify this assumption? Is this assumption always true? What if...?

- Clarification. What are your most important points? How does this relate to that? Can you give an example? Can you summarize the key points? What do you mean by ...? What are the causes and effects? What are alternative viewpoints or perspectives?

- Evidence. Can you provide examples and non-examples? Can you explain your reasons? Can you justify your position? Can you cite sources that support your argument? What resources did you use to identify information? What resources did you ignore? How did you evaluate this information?

- Focus. How can we approach this topic? What is the main issue and supporting questions? What alternative views can we consider?

Course Discussion: Facilitation

When there's a lull in the discussion, it's tempting for instructors to interject their ideas and opinions into student forums. However, teachers should use caution when posting messages. Some students may rely on the teacher's comments or wait for the teacher to lead rather than jump into the discussion. When possible, let the participants lead and only join the discussion when necessary.

There are situations where the instructor may wish to enter a student discussion. He or she may jump into a heated conversation to cool things off, provide a perspective that seems to be missing, play the devil's advocate, or correct misleading information. However, take care not to anger or embarrass students. It may be possible to defuse a situation through a personal email rather than a public posting.

Many instructors find it valuable to setup and debrief discussions. The setup might include the discussion prompt, assessment information, and suggestions for approaching the topic. At the end of discussion, the instructor may provide an overview of the discussion along with a closing statement. This is also a role that can be rotated among students.

When facilitating discussions…

- let the discussions flow

- avoid adding comments that might lead or distract

- be patient, students will self-correct over time

Facilitating Online Discussions

At first, some students may need guidance and practice in holding an online discussion. If your discussions get off-track or lack depth, you may wish to play the role of coach by:

- encouraging participation with supportive comments

- modeling a quality response such as providing an example or playing the devil's advocate

- stimulating discussion with focused questions requiring clarification or elaboration

- refocusing the conversation back to the original problem or prompt

- asking questions that require students to state assumptions, evidence, options, reasons, consequence, or implication

- responding to a posting that has been ignored

- identifying patterns of responses

- summarizing progress and outlining areas of potential for future discussion

- synthesizing comments

Regardless of whether you choose to actively participate in student discussions, consider the following guidelines for class discussions.

- provide a practice area to practice posting messages, uploading documents, etc.

- model expectations through practice exercises such as Introduce Yourself activities

- provide clear guidelines

- present a springboard/starter (motivation, task, materials, guidelines)

- encourage your best students to post early

- stay out of the discussion

- guide as needed

- review reply/feedback/discussion enhancement guidelines

- require participation

- debrief, draw conclusions, and closure (you and/or students)

- establish the foundation for future assignments (connect to new content, relate to other topics, reflective and anticipatory questions)

Creating a Series of Discussions

Rather than cramming the entire class into the same discussion, provide choices. In most cases, you need at least three or four people to really get a discussion rolling, however too many students will make a forum overwhelming. Groups of four to fourteen students work best. You may allow students to self-select categories (i.e., topics, professional interests, grade level interests, problem, team) or assign groups.

If you allow self-selection, keep track of the choices made by students and adjust the assignments each semester in an attempt to even out the groups.

Examine different aspects of your learning outcome and select two or three elements discussion. You may ask students to post in one discussion and reply in another forum.

Try It: Infographic Discussions

Try It: Infographic Discussions

Use an infographic as the basis of discussion.

Explore some information examples.

Periodic Table of the Internet - Could you make a Periodical Table of research?

Science Fiction and Fantasy Books - Can you create your own chart showing your favorite books?

TurnItIn: The Plagiarism Spectrum - Do you think plagiarism is a problem? Are you surprised by the statistics in the infographic?

Wikipedia: Redefining Research - Select and verify one of the statistics.

Explore some health examples.

Human Subway - Is this graphic correct? Trace each system. Is anything missing? What other analogies could you use to visualize the human body systems?

Male Death - Categorize the data. Which are you most likely to encounter as an EMT?

Our Favorite Drugs - What drugs are you likely to encounter as an EMT?

PTSD - What are implications for EMTs?

Emergency Communication - Are you prepared for a disaster? What other communication systems should be considered as part of this infographic?

In the Event of Zombie Attack - Could you create an infographic focusing on a real-attack? How would it be like and unlike this infographic?

Try It: Discussions

Try It: Discussions

Explore the ideas related to discussions.

Select one idea and design a class discussion.

Games

Games are an effective way to review course content and apply skills to new situations.

Games are an effective way to review course content and apply skills to new situations.

- Games increase emotional involvement. Information is more easily remembered when connected to strong emotions.

- Games involve decision-making skills and require students to apply knowledge of facts.

- Games increase interest in learning.

- Games involve students with others. People put forth more effort in cooperative and competitive situations.

- Games increase self-confidence.

Games involve overcoming obstacles to solve a problem, accomplish a goal or complete a task.

Read!

Read!

Read Marino, Megan (2013). Revitalizing traditional information literacy instruction: exploring games in academic libraries. Public Services Quarterly, 9, 333-341.

Think about how games might apply in your area of interest.

When designing a game, you simply need four elements:

- Goal. What is the goal for the game? How do you win?

- Rules. What rules are in effect during the game?

- Feedback. How will progress be tracked? Is there a gamemaster in charge?

- Motivation. Why play the game? What can be learned?

Try It!

Try It!

Go to BiblioBouts and try the demo game.

Does this experience have the elements of a game?

Read Students' Behaviour Playing an Online Information Literacy Game by Karen Markey and Chris Leeder.

Learn about the design and use of educational games for teaching information skills.

Categories of Games

Game Shows

- Are You Smarter than a 5th Grader

- Family Feud

- Jeopardy

- Want to be a Millionaire

- Wheel of Fortune

Guidelines

- Focus on a very specific learning outcome.

- Provide a review for every answer slide

- Keep it short, around 7 questions

- Introduce, Practice, Review a topic – match activity

- If it’s practice, they already need the content

- Use graphics, sounds effects to provide a different “feel” than content presentations

- Create some Powerpoint templates to share.

- Audience Respond options

- Use signs you distribute, only instructor sees

- Move to different parts of the room, discuss and defend the answers.

- Small groups… discuss answer and use dry erase board

Card Games

Question cards. Pick a card and match to the case, person, problem.

Patient cards. Pick a patient (i.e., headshot with description) and make a decision.

Example. Read the card: Your patient converses with you and answers most questions appropriately but is unsure of where she is or who you are. Her mental status is best described as… Place the card in the correct category: Unresponsive, Responsive to painful stimuli,Responsive to verbal stimuli, Alert

Review cards. One table creates questions for another table. The instructor should review cards before trading with another table.

Example. Make words by matching common prefixes or suffixes with the rest of the word. This is a great game to play before class. Place words on tables before class.

Dice Games

People like to roll dice. Roll the dice to

- determine your group

- the type of card you'll take

- the station where you'll start

- the symptoms of your patient

- determine the word you'll define... count down the list.

- the order of play

Example. If you roll a BLANK, then you must BLANK

Board Games

Trivia Pursuit

- Draw hotwheels and use them as your playing piece.

- Provide four questions on each card. Roll dice to determine category of question. Topics: calls, assessment, transport, cleanup or the ABCDEs

Matrix Games

- Create a game board containing topics across the top and characteristics along the side. Draw a card. Place the card into a box on a large matrix. The gamemaster checks answers.

Hands-on Games

- Fracture Splinting with tongue depressors

- Scene Evaluation – matchbox cars and town carpets

- Safety Scenario – toy gun and knives

- Scenario Fixing – What’s missing from this situation

Other Games

4Cs

- Present a slide with the 4Cs:

- Components are parts of a concept. Example: checking airway

- Characteristics are features of the concept. Example: speed

- Challenges are obstacles. Example: weight of patient

- Characters are people involved. Example: patient

- Each team works on a C. 3 minutes to collect, 3 to analyze.

- Present ideas. Look for commonalities, differences, surprises and missing data.

Scavenger Hunt

- Provide a sheet with patient information. Collect the equipment needed. Check for accuracy.

Try It: Firehouse Football

Try It: Firehouse Football

Mission. Answer questions correctly to score points.

Step 1: Layout the football field and place the ball on the 50-yard line.

Step 2: Divide the group into 2 teams and name a referee (one the ref can be on a team). The oldest player goes first.

Step 3: The first team picks a card and the referee reads the question and marks the yardage based on the difficulty of the question. Use a post-it to mark first downs.

Easy Question: 5 yards if correct, miss it and no gain

Medium Question: 10 yards if correct, miss it and no gain

Difficult Question: 25 yards (but if you miss it, there's an interception)

Step 4: You get four downs to make 10 yards. If you don’t make it, the other team takes over. If you make it, you keep going until you score or lose the ball.

Step 5: After a touchdown, the other team takes possession on the 50-yard line.

Step 6: In a regular classroom, play 4-twelve minute quarters.

Step 7: Brainstorm modifications to the rules.

Step 8: Discuss whether this is an effective review tool or if the game distracts from learning. Talk about ways the game could be changed to increase learning.

Print out firehouse football cards and answer sheet.

Adapt this game for an information literacy topic. Or, create one based on another sport.

Timers and Grouping Tools

Online tools like timers, coin flippers, spinners, and other tools are useful in planning classroom games.

- Best full-screen countdown.

- Online Stopwatch (Count up) Choice 1, Choice 2

- Online Timer (Count down) Choice 1, Choice 2

- Online Clock

- Playing Card Shuffler

- Coin Flipper

- Spinner

- Randomizer - list of options

- Download classroom timers as PowerPoint slides.

Looking for more? Explore the Games & Simulations for Healthcare database.

Try It!

Try It!

Brainstorm game formats that could be adapted for use in your classroom.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to Web-based Games.

Explore the characteristics of an effective online game.

Interactives and Learning Objects

Interactives are software tools that facilitate computer to human interaction. In other words, communications are sent between the human and the computer forming a relationship. When people design learning spaces for this type of computer-based interaction, they're sometimes called interactives.

Increasingly, courses are using online games, tutorials and simulations.

Example. The Cyberbee Copyright interactive presents questions and answers.

Example. Try the Keyword Challenge. This activity helps participants practice keywords.

Tutorials

Tutorials are interactive that are self-contained modules of instruction focused on specific learning objectives. Tasks are generally broken down in to 5 minute to 60 minute segments. Individuals generally work through tutorials at their own pace.

Tutorials generally provide an introduction, new information, examples, practice with feedback, and a self-assessment. Although they may be text-based, tutorials are increasingly incorporating audio, video, animation, graphics, and interactive elements.

Tutorials present step-by-step instruction teaching new concepts. They are designed to provide new information along with examples and nonexamples of concepts. In addition, practice and feedback is often incorporated into the program. Tutorials work well when

- introducing new concepts

- reviewing difficult ideas, or

- providing enrichment.

Some tutorials are often linear. In other words, they provide the same information and examples to all learners in a predetermined order. Sometimes called "electronic pageturners" they may not address the needs of individual students. As such, when designing tutorials consider incorporating optional examples, different channels of communication such as audio, video, graphics, and different ways of viewing the content.

Branching tutorials provide alternative paths through learning. Each student receives that instruction he or she needs based on responses to specific questions or problems.

The strength of tutorials lies in their consistency and accuracy. They allow students to work at their own pace and provide individualized practice and feedback which is difficult to do in the traditional classroom environment.

When selecting tutorials consider the instructional strategies incorporated into the program. Ask yourself:

- Does it teach the concepts like you would teach them?

- Do you like the quality and quantity of examples and nonexamples provided?

- Does the vocabulary match what you teach in class?

- Is the software a good use of instructional time in your classroom?

It can be confusing for a student to learn one approach in the tutorial and be expected to demonstrate a different technique in an exam.

Web-based tutorials have become a popular approach to information instruction.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to Web-based Tutorials.

Explore the characteristics of an effective online tutorial.

In Pegagogical considerations in developing an online tutorial in information literacy, Skagen and others (2009), stress the creation of learning objects that guide students through the research process. Go to Search and Write to explore their tutorial.

Weiner, Pelaez, Chang, and Weiner (2012) studied an online information literacy tutorial designed for first-year biology and nursing students. Students indicated that they liked learning online, but they thought the modules could be shorter. They also requested video and audio content in addition to text. They concluded that

"Online learning can be effective if the learner perceives it as useful. Non-linear learning that occurs through tutorial modules is a desired approach that provides access to the content of interest at an optimal time through self-directed learning. This concept enhances interest and learning capability." (Weiner, et al, 2012, 196)

In Share and share alike: barriers and solutions to tutorial creation and management, Deitering and Rempel (2012) found that time and technological expertise were the most common barriers to tutorial creation for instruction librarians. They recommend using content management systems, web-page tools, and subject guides like LibGuides to assist in project development.

Go to Tutorials and Library Instruction from the University of Missouri St. Louis University Libraries. Try one of their interactive tutorials. Notice how they provide interactive aspects and questioning.

Try It: Interactives

Try It: Interactives

Evaluate three of the interactives above and share your findings.

Final Assessment. Think about ways to assess “participation.”

- Self-check. Ask students to write about their experience.

- Peer check. Pair students and ask them to check off each other.

- Instructor check. Checklist of completed activities. Check on accuracy through testing.

Interactive Tools and Simulations

Increasingly, online courses are using online games and simulations. Many of these interactives use Adobe Flash technology. Explore lots of examples by subject area at Flash Exploration.

Explore examples of tools:

Explore examples of tutorials and simulations:

- CogLab 2.0

- Design a Panda Habitat at Conservation Central

- Destination Modern Art from The Museum of Modern Art

- DNA Interactive at the Dolan DNA Learning Center

- Economics Interactives from the International Monetary Fund

- Interactives Archive at PBS NOVA

- Interactive Body from BBC

- Solar System Simulator at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology

- Making Vaccines at PBS NOVA

- Middle East Politics Simulation at Macquarie University

- Pathways to Freedom: Maryland & the Underground Railroad from Maryland Public Television

- Physics Simulations at University of Colorado at Boulder

- Wave on a String (Flash Example) from PhET Interactive Simulations, University of Colorado

- WebSim - A Simulation Based Electronic Circuits Laboratory at MIT

Explore examples of off-line games that could be turned into online games:

- Games Economists Play by Greg Delemeester and Jurgen Brauer

Read!

Read!

Read Good For What? Considering Context in Building Learning Objects by Meredith Farkas (2013).

Practical Projects

Involve students in activities that result in the authentic, meaningful products.

Carol Kuhlthau (1994) identified three elements as necessary in a research assignment.

- The Question. The question raised cannot be thoroughly investigated and resolved within the confines of the curriculum materials.

- The Materials. There must be materials available to address the question including a range of resource in the library.

- The Presentation. The findings of the research must be presented in some way through a print, visual, and/or auditory format.

As students work on projects, teachers sometimes provide one-shot or just-in-time lessons. One shot lessons provide instruction on a particular topic prior to students beginning an assignment, while just-in-time instruction assists students at the specific time and place when they need help.

Van Epps and Sapp (2013) found that the just-in-time approach was more effective.

Product Expectations

Tired, traditional assignments bore both students and faculty. Spice up your classes with alternative products that engage learners in authentic learning experiences.

Products and Plagiarism