Audience Analysis

At the completion of this section, you should be able to:

- identify learner characteristics and their implications

- conduct and apply an audience analysis to instructional design

- incorporate key ideas found in the literature related to learning styles into instructional materials.

- adapt instruction to meet the needs of adult learners.

- apply learning styles to the creation of classroom activities.

- reflect on your own learning preferences and how they shape you as a learner and teacher.

Begin by viewing the class presentation in Vimeo. Then, read each of the sections of this page.

Explore each of the following topics on this page:

Learners

Librarians know what needs to be taught, but it's equally important to know what approaches will be effective, efficient, and appealing to a specific audience. Start with a few basic questions:

- Who will I be teaching?

- What are they like as learners?

- How do they typically behave in the type of situation in which I'll have them?

- How will I accommodate those characteristics?

An understanding of the audience will help to determine the type and amount of information you will provide, as well as the format of your session.

Blanchett, Powis, and Webb (2012, 14) stress that a needs analysis "may strongly influence the 'what' of your teaching, but the learner analysis will influence the 'how'." They suggest asking the following questions about learners (Blanchett, Powis, & Webb, 2012, 13-14):

Blanchett, Powis, and Webb (2012, 14) stress that a needs analysis "may strongly influence the 'what' of your teaching, but the learner analysis will influence the 'how'." They suggest asking the following questions about learners (Blanchett, Powis, & Webb, 2012, 13-14):

- What knowledge will they already have?

- What fears might they have?

- What do they want to know?

- What is their motivation?

- What are their learning styles?

- Do they have any special requirements?

- What are their cultural references?

- What level of autonomy do they have?

- What are their experiences of education?

In Tailoring information literacy instruction and library services for continuing education, Lange, Canuel, and Fitzgibbons (2011) discuss the need to adapt information literacy initiatives to meet the needs of new audiences. They developed an information literacy program to reach continuing education learners. They began by identifying the needs and characteristics of their audience. Then, developed teaching techniques to meet the challenge of their diverse audience. The researchers addressed challenges with specific strategies and identified benefits. Lange, Canuel, and Fitzgibbons (2011, 77) used

"information literacy instruction, promotional activities, and targeted collection development with specific educational objectives... Particular successes have included adapting instruction strategies for students with varying levels of language, library, and technology skills, teaching outside usual "business hours," teaching online, integrating services in the curricula, communication with students and instructors in their own continuing education context, and developing entirely new sessions based upon the content specific to continuing education programmes. "

There are many ways to collect information about learners. Blanchett, Powis, and Webb (2012, 16-17) suggest a pre-session audit when conducting a one-session event.

- Ask the other stakeholders - teachers, lecturers, societies, individuals

- Ask the learners - questionnaires

- Ask as students enter the room

- Ask as the session begins

- Use student introductions to collection information

- Use a quiz or introductory activity to assess student knowledge

When possible, collect data ahead of time. If information is gathered after the session has been planned, data can be used to made adjustments "just in time".

Audience Analysis

Knowing your students is the key to teaching. Callison and Lamb (2006) state that "audience analysis involves the processes of gathering and interpreting information about the recipients of oral, written, or visual communication."

Callison and Lamb (2006) recommend asking the following questions:

- What is the relationship of the author to the audience and how will this impact the formality of the communication or other considerations?

- What does your audience know about the topic?

- What positive or negative experience might they have about the topic?

- What attitudes, biases, or strong feelings might your audience have toward the topic?

- What misconceptions might the audience have about your topic?

- What is the level of expertise on this topic for most of your audience members?

- What background information does your audience have about the topic?

- To what extent do you want to change the opinions held by your audience?

- To what extend do you want to inform or educate your audience?

- To what degree do you want to entertain your audience, or how will a more entertaining manner of delivery help to engage your audience and keep their interest?

- What are the expressed and perceived information needs of the audience?

- What are the important basic terms, assumptions, events, and names that your audience should know in order to gain the most meaning from your message?

- What might be confusing jargon, or overly technical terms and meaningless acronyms, that should be avoided?

- What format of communication would be most effective for this audience (i.e., report, action plan, story, persuasive message, presentation, debate)?

- Is there a need to provide information in a visual form to help your audience understand aspects of your message that otherwise may be too complicated, too abstract, or not relevant?

- What is the most important message for this specific audience so these key ideas are emphasized in the introduction and reinforced in the conclusion?

Callison and Lamb (2006) suggest that in the case of complex content or persuasive messages, additional questions might be asked:

- How does the speaker or writer relate to the audience in terms of social groupings such as age, gender, religion, ethnic or cultural factors, family status, sexual orientation, educational level, and social-economic class?

- Is your audience very small or large? What are the implications of this composition?

- Is your audience heterogeneous or homogeneous? What are the implications of this composition?

- Does your audience have a problem that you can assist in solving?

- What are the roles of your audience members (i.e., followers, leaders, decision makers, advisors, creators)?

- How does the audience perceive your competence and confidence, character, and good will?

- What authorities or information sources will the audience most likely accept or reject?

- How does the speaker or writer relate to the audience in terms of ideology, values, beliefs, and attitudes?

- Is there a potentially friendly and accepting audience or an audience that is likely to be hostile and confrontational?

- Is your audience likely to be more receptive to analogies, testimonials, logic, minor general statistics, or complex and in-depth data?

- How does your audience feel about its past, present, and future relative to your controversial topic?

- Have members of your audience had personal experiences that may influence how they will receive your message?

- Will your audience be allowed or even encourage to respond to your presentation?

The closer the instructor can come to understanding the learner's abilities, experiences, and expectations, the more likely the communication is to be effective. Are your students young children beginning to read, lawyers seeking technology skills, or retired seniors looking for opportunities to volunteer?

Audience Information

What do you need to know about your target population? Dick, Carey, and Carey (2011, 93-94) suggest collecting information in eight areas:

- Entry Skills. What skills have your students already mastered associated to the learning goal? Are they ready for instruction?

- Prior Knowledge of Topic Area. What do students already know about the topic? How can new knowledge be based on prior experiences and existing skills?

- Attitudes toward Content and Potential Delivery Systems. What do students think about the topic? What are learner expectations and preferences related to the new content?

- Academic Motivation (ARCS). How relevant is this instructional goal for students? What aspects of the goal will be interesting to students? How satisfying will it be for students to succeed in performing the goal?

- Educational and Ability Levels. What academic and general education skills do students possess that will be helpful in their learning?

- General Learning Preferences. What types of learning situations do your students prefer? Do they like case studies, collaborative work, or a lecture environments? Do they prefer demonstrations or hands-on activities?

- Attitudes Toward the Organization Giving the Instruction. How do students feel about the mission of the library? What are their prior experiences with learning through the library?

- Group Characteristics. Is your group homogeneous (everyone has similar skills and background) or heterogeneous (wide range of learner types)?

Characteristics and Implications

Your audience can be described in terms of general characteristics and implications of these characteristics.

Learner Characteristics. Who are your students?

- Entry Knowledge and Skills (i.e., reading level, knowledge of information tools, technology skills, experience)

- Demographics (i.e., age, gender, cultural background, education background, socioeconomic status)

- Predispositions (i.e., interest, motivation, aptitudes, problem-solving skills, desires)

Example: All students have a high school diploma or GRE, however many have a low reading level and lack interest in reading.

Implications of Learner Characteristics. What are these people like as learners?

- How will learners behave in the classroom situation?

- How can accommodations be made based on characteristics?

Example: When offering the parenting class at the public library, the characteristics of students must be consider. Rather than large blocks of reading, materials will be presented in chunks at the lowest reading level necessary to address the learning outcome. Visual examples will be used to supplement text-based examples.

Read!

Read!

Read Instructional preferences of first-year college students with below-proficent information literacy skills: a focus group study by Don Latham and Melissa Gross (2013).

Entry Skills

What knowledge, skills, and attitudes do your learners possess when they enter your session?

Entry skills are the building blocks upon which your instructional depends. Without these entry skills, a learners would have a difficult, if not impossible, time trying to learn from your instruction. For instance, students must know the composition and structure of a cell prior to learning about mitosis.

Entry skills should be indicated with a dotted line on you instructional analysis chart. These are very specific skills that relate directly to your instruction. If a student doesn't know how to find the school's website, they're going to have a tough time filling out an online form found at the website.

Revisit Instructional Analysis

After completion of the audience analysis, it's important to go back and revisit the instructional analysis. Dick, Carey, and Carey (2011, 99) recommend discussing the instructional analysis with a small group from the target audience to be sure they "get" the approach and content. It may also be necessary to adjust the entry skills line. In other words, you may find that a majority of your students lack an entry skill or already possess one of the proposed skills.

Audience Examples

Middle School Example

- Situation

- As part of the CIPA requirement for schools to teach "appropriate use of Internet", the librarian and health teacher have teamed up for a series of lessons focusing on key issues such as network privacy and cyberbullying.

- Goal

- The students will be able to identify examples of cyberbullying, resist peer pressure to bully, and describe the steps in dealing with situations involving cyberbullying.

- Learner Characteristics

- Seventh grade health education class held in the library. Twenty-five students; half boys and half girls; can sit and listen for 10-15 minutes, restlessness sets in after that; class responds thoughtfully in discussions, especially if relevant to their immediate lives; students often rely of the opinions of peers rather than forming an independent stand; most of these students are eager to contribute their ideas; all students have computer accounts and access to together, most students have cell phones and use social networks, and some of the students have experience with cyberbullying.

- Implications

- The age of the group indicates the need to present realistic examples and use concrete vocabulary. Because of the size of the class, the presentation will need to be projected. Because of their attention span and immediate relevancy of the topic, the activities should shift from information presentation to audience participation every ten minutes or so.

- Revisit Instructional Analysis

- Students have lots of experience with technology, but lack maturity in dealing with social networking situations that involve peers pressure. The instructional analysis will shift some of the technology skills to entry skills. The instructional analysis will expand the section dealing with peer pressure.

Upper-division Nursing Example

- The Situation

- As part of an upper-division communication course in the nursing curriculum, the embedded librarian is planning a series of sessions on communication and evidence-based practices.

- Learner Characteristics

- Most of these nursing students have at least five years of nursing experience, at least one year of supervisory experience, and are presently supervising teams of at least five people. All of them are working on their bachelor's degree and have completed a number of other university credit courses. They are motivated to complete assignments, they can read and write effectively. The students are all reimbursed for their successful completion of any course (C or better) and the supervisors are required to continue their education until their degrees are completed. The students have had an introduction to evidence-based practices and have skills in using the popular medical databases. Other characteristics include (1) effective assertive communicators, (2) "to blame" if communication is not totally accurate and (3) more able to develop "positive" relationships with doctors, other nurses, staff, and patients. They tend to take thorough notes, ask questions in class, and share personal examples of communications readily. They tend to know one another and are open and honest in talking about their concerns. They are looking for tips. The class is all women who also have families. Therefore, they are often concerned with how skills learned will be useful with personal as well as professional relationships.

- Implications

- First of all, the advanced skills, motivation, and work experience of the students mean that the instruction need only check out their entry skill level of communication, provide some "refreshing" review and build on previous learning and work experience. The practical application of these skills will be the primary focus because of the students' professional and personal possibilities for using them. Instruction will need to include case studies, role playing, "action homework," and concrete examples from hospital and family interactions. The students' openness and willingness to share will make it possible to use pair exercises, small group activities, and class discussion of real and simulated situations involving action communication. Students will also be asked to identify specific professional and personal results (goals and objectives) they would like to achieve in the area of effective communication. Since they are looking for tips or "pat answers," this may block their flexibility and willingness to view all these skills learned as useful and all this will be included in the instruction. The reading level of the materials will be aimed at upper-division undergraduates and graduate students because of the maturity and expertise of the class. The examples and situations used throughout the instruction will be aimed at typical, yet more complex, instances common to supervisors, experienced, employees, and parents.

Try It!

Try It!

Spend some time thinking about your library users.

What are the typical entry skills, demographics and predispositions of your students?

How does that impact learning?

Learning Styles and Preferences

Many approaches to learning styles have emerged from psychological theories and educational research over the past several decades. The value of understanding learning styles comes from developing insights into the individual differences, needs, and preferences of learners.

Many approaches to learning styles have emerged from psychological theories and educational research over the past several decades. The value of understanding learning styles comes from developing insights into the individual differences, needs, and preferences of learners.

By understanding different styles of learning, it's possible to design instruction that reaches a wide range of learners.

Example: A lecture followed by a text-based, multiple-choice exam would appeal to learners who need or enjoy passively listening to information and conveying their understandings through text. A person with verbal preferences would do well, however a learner with a visual or tactile need might be unsuccessful. A better approach might combine a number of ways to convey information and involve students in the learning process through the use of visuals, discussion, and hands-on activities.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to the What Is Your Learning Style page and try the questionnaire.

Or, try that Find Out What Your Learning Style Is (Word) for a quick look at multiple intelligences from the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council.

It's important to distinguish learning styles from learning preferences. While some students may learn best through a particular approach, they may have a preference for another. For instance, while a student may learn well through a text presentation, they may prefer to watch a video.

Since the 1970s, educators have used learning styles as a way to address the individual needs of students. Most students have preferences for how they learn, however recent research questions whether tailoring instruction to individual learners is effective.

Recently, the use of learning styles has come under attack. Some psychologists challenge the validity of the research and its application to teaching.

The bottom line…

Cast a wide net of options to engage learners with different preferences and learning styles.

Read!

Read!

Read Realizing the Democratic Potential of Online Sources in the Classroom by Valerie Burton and Robert C. H. Sweeny. How does the proposed approach to teaching about online sources connect with the audience?

Try It: Preferences

Try It: Preferences

Explore three different ways to learn about plagiarism.

Cite is Right Animated Video

Plagiarism (flash version) or (no flash version)

Plagiarism Rap

Plagiarism Tutorial

Which approaches did you like and dislike? Why? How do you learn best? How do you know? What is your preference? Are your preferences similar or different from the people you know? Why is it important to provide opportunities and options for learning?

Let's explore FOUR areas where learning styles can be applied to developing effective, efficient, and appealing instructional materials that reach all of your learners (Adapted from Felder and Silverman).

1 - Preferences

What type of information does the student preferentially perceive? Which do students like best? Match how students perceive with corresponding content.

- Sensing learners - concrete, practical, oriented toward facts and procedures (sights, sounds, sensations). They like solving problems based on facts. They don’t like surprises. They are slower at translating symbols like words, so may time out on tests.

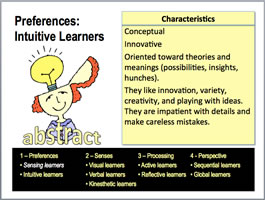

- Intuitive learners – abstract, conceptual, innovative, oriented toward theories and meanings (possibilities, insights, hunches). They like innovation, variety, creativity, and playing with ideas. They are impatient with details and make careless mistakes.

Example. Provide a balance of concrete information and abstract concepts. Provide practical examples of theories. Balance practical problem-solving methods with fundamental understanding. Provide explicit illustrations of theoretical patterns (inference, patterns, generalizations). Provide opportunities for observation, experimentation, and attention to detail.

Activity. Provide examples, describe the theory, show the consequences, present applications.

2 - Perceiving

Through what sensory modality is information most effectively perceived? What’s the best way to present content? Match how students receive information with types of presentations.

- Visual learners - see - prefer visual representations of presented material (pictures, timelines, diagrams, flow charts, films, demonstrations). They tend to forget what people say, but remember visual demonstrations.

- Verbal learners - read - prefer written and spoken explanations (readings, lectures, discussions). They prefer a verbal explanation and get a lot out of discussions.

- Kinesthetic learners - do - hands-on demonstrations, movement, organizing physical objects

Example. Use pictures, graphics, sketching (before, during, and after). Show video segments. Use live demonstrations. Incorporate and movement into lessons.

Visual-Verbal-Kinesthetic Activity. Ask students to compare two photographs (visual) and discuss (verbal) their findings. Then ask them to re-create (kinesthetic) one of the scenes.

3 - Processing

How does the student prefer to process information? How do students like to work with content? Match how students process with student participation activities.

- Active learners – experimenter, learn by trying things out, working with others, testing out ideas, explaining to others (through physical engagement or discussion with others). They do poorly in lecture situations where they simply listen and aren’t asked to “do”. They do well in groups. Ask them to evaluate ideas, carry out experiments, and find workable solutions. They are organizers and decision-makers.

- Reflective learners – observer, learn by thinking things through, working alone (through interpersonal thought and quiet activities, watch & listen). They do poorly in lecture situations where they simply listen and aren’t given time to “think” . They do best by themselves. Ask them to define problems and propose solutions. They are modelers and thinkers.

Example: Alternate lecture with pauses for thought and opportunities for problem-solving activities. Materials should present both practical problems and fundamental understandings that bridge theory and practice.

Questioning Activity. Seated in small groups. Pose an open-ended question and give time to read and think. Then, ask students to come up with collective answers to questions. Provide 30 seconds to five minutes. Discuss alternative solutions and answers. Or, show possible answers and ask students to discuss solutions. Provide time in class to simply “think” in the form of creating an example, brainstorming solutions, categorizing ideas, thinking about what has been learning, thinking about what’s still muddy, thinking about ideas that don’t fit the theory.

4 - Perspective

What type of perspective is provided? How does the student progress toward understandings? How do students “put it all together”? Match how students understand with different perspectives.

- Sequential learners – “the trees” - linear, orderly, learn in small incremental steps (continual chunks of information, step-by-step progression). They follow sequential content learning along with way. They can work with ideas they only understand superficially. They are good at convergent thinking and analysis.

- Global learners – “the forest” - holistic, system thinkers, learn in large leap, context and relevance (large jumps, big picture, and “lightbulb” moments). They may be lost for a while and suddenly “get it.” They may not be able to explain how they got to solutions, however they are great at seeing connections between disciplines. They are good at divergent thinking and synthesis. They are great at seeing the big picture, but can become lost and frustrated when dealing with individual skills and facts.

Example. Most classrooms are designed to meet the needs of sequential learners. To reach global learners, be sure to provide the “big picture” and learning outcomes for each class period. Establish the context and relevance of content and relate it to student experiences. Use “what ifs” and involve students in seeing the impact of decisions. Show how content fits into more advanced concepts. Ask students to design alternative solutions for problems. Applaud creative solutions, even incorrect ones.

Whole-Part-Whole Activity. This works well for both analytic and global learners.

- WHOLE: Demonstrate the entire skill, beginning to end while briefly naming each action or step. Ask students to wait for questions.

- PART: Demonstrate the skill again, step-by-step explaining each part in detail. Take questions as needed.

- WHOLE: Demonstrate the entire skill, beginning to end without interruption or commentary.

As you design instruction, use a variety of strategies to reach different types of learners. You don't need to throw in the kitchen sink, however you never know what might reach a learner.

Try It!

Try It!

Want to have some fun? Find some friends and try out the following activity.

1. Select and read a learning styles card (click the card on the right to download the cards).

2. Find the other people with a card in your category:

Preference, Perceiving, Processing, or Perspective.

3. Share the characteristics described on your card.

4. Discuss whether your learning style is more like your card or a peer's card.

5. Brainstorm a class activity that would meet the needs of all learners in your category. Use the last couple handout pages for ideas.

6. Set a timer to five minutes to mark each round. At the end of five minutes, switch cards with a member of another group and complete steps 2-5 again.

Need class topic ideas?

Need class topic ideas?

• Identify the elements of a citation.

• Demonstrate the use of X database.

• Identify a broad topic, narrow topic, and related topic from a list of topics.

• Demonstrate the skill of using the hand scanner.

• Identify the elements of a book from the title page.

• Conduct an oral history interview.

• Explain the rationale for the library's security system.

• Differentiate between primary and second sources.

• Demonstrate the steps in using X piece of equipment or Y process.

• Identify different types of reference source.

Resources

Blanchett, Helen, Powis, Chris, & Webb, Jo (2012). A Guide to Teaching Information Literacy: 101 Practical Tips. Facet Publishing.

Callison, Daniel and Lamb, Annette. (2006). Audience Analysis. In Key Words, Concepts and Methods for Information Age Instruction: A Guide to Teaching Information Literacy. LMS Associates.

Dick, Walt, Carey, Lou, and Carey, James O. (2011). The Systematic Design of Instruction. Seventh Edition. Pearson.

Felder, Richard (1988). Learning and learning styles in engineering education (PDF). Engineering Education, 78&7), 674-681.

Lange, J., Canuel, R. and Fitzgibbons, M. (2011). Tailoring information literacy instruction and library services for continuing education. Journal of information literacy, 5(2), 66-80. Available: http://jil.lboro.ac.uk/ojs/index.php/JIL/article/view/LLC-V5-I2-2011-1

Moallem (2007-2008). A guidelines for developing instructional materials considering different learning styles (PDF).