Overview

At the completion of this section, you should be able to:

- define and apply vocabulary related to information instruction.

- describe and give examples of life-long learning.

- distinguish between informal and formal learning situations.

- define information inquiry and describe how it's connected to the librarian's instructional role.

- synthesize definitions of information literacy and associated literacies.

- describe the hierarchy of information exploration and the place of information fluency.

Begin by viewing the class presentation in Vimeo. Then, read each of the sections of this page.

Explore each of the following topics on this page:

- Definitions

- Life-long learning

- Informal and Formal Learning

- Pedagogy & Andragogy

- Information Inquiry

- Information Literacy

- Associated Literacies

- Information Fluency

- Resources

Definitions

Why is this course important for library professionals? A recent study published in College & Research Libraries (Hall, 2013) found that “supervisors highly value library instruction” and seek out library professional with these skills.

This course is intended to support library and information professionals in the creation of effective (do they work?), efficient (are they a good use of time?), and appealing (are they engaging?) teaching and learning environments.

This course is intended to support library and information professionals in the creation of effective (do they work?), efficient (are they a good use of time?), and appealing (are they engaging?) teaching and learning environments.

Olivia is a health care professional. She has a passion for learning, but realizes that she lacks some of the 21st century skills of her classmates. Where can she get these skills?

Before we jump into instructional design, let’s define some concepts.

Information is an organized collection of data. The value depends on the usefulness, meaningfulness, and context of the message.

Instruction is the process of facilitating the acquisition of information and application of knowledge, skills, dispositions.

Training is the process of acquiring a specific skill to improve performance or achieve a particular goal.

Teaching is the act of motivating students in ways that help them learn.

Learning is the acquisition of knowledge, skills, or dispositions through instruction, study, practice, or experience.

Information Inquiry is the process of asking questions, examining information, and drawing conclusions to address an information need.

Kyle is overflowing with questions. Reading the book Shiloh by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor stimulated Kyle's interest in the care of animals. He's exploring information about a career as a veterinarian. What do veterinarians do? What education is required? Is there a need for vets? Would he make a good vet? How will he develop the skills needed for his inquiry?

Life-long Learning

Life-long learning is the process of acquiring and expanding knowledge, skills, and dispositions throughout your life to foster well-being.

Life-long learning is the process of acquiring and expanding knowledge, skills, and dispositions throughout your life to foster well-being.

It's much more than taking an adult pottery class or reading a nonfiction book occasionally. It's about the decisions you make and the problems you solve in everyday life.

From enrolling in a structured, formal education program to considering whether to believe an infomercial's gimmick, lifelong learning takes many forms.

Life-long learners choose to seek out new ideas and alternative perspectives. They embrace our changing, dynamic, information-rich society by keeping their senses active and their minds full of ideas. Much of this learning is self-directed. To be successful, the child or adult must have basic information inquiry knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

The Museums, Libraries and Archives Council has developed the Inspiring Learning Framework to describe a "broad and inclusive definition of learning" identifying that:

- Learning is a process of active engagement with experience

- It is what people do when they want to make sense of the world

- It may involve the development or deepening of skills, knowledge, understanding, values, ideas and feelings

- Effective learning leads to change, development and the desire to learn more

Watching the Home & Garden channel program to learn about home improvement, visiting your library to locate good books and movies, or exploring your local museum are all examples of enjoying life's opportunities. The key is motivation. Making an informed decision can lead to a positive career choice or a successful marriage.

Watching the Home & Garden channel program to learn about home improvement, visiting your library to locate good books and movies, or exploring your local museum are all examples of enjoying life's opportunities. The key is motivation. Making an informed decision can lead to a positive career choice or a successful marriage.

Life-long learning isn't just about emotional well-being. According to medical research, people with active minds are less likely to suffer Alzheimer's Disease and other ailments.

As librarians and educators we need to model the kind of life we envision for our students including enthusiasm for life, love of reading, and life long learning!

Lifelong learning is about anticipation, exploration, and reflection.

Lifelong learning is about anticipation, exploration, and reflection.

Think about your own life. How has your time been spent? How would you like to spend your time? Each person makes their own choices and decisions about learning. What will yours be?

Brainstorm all the ways that you learn in your life.

Read!

Read!

Read Public Libraries: Impact of Public Libraries on Students and Lifelong Learners (October 2012).

What do you see are the role of libraries in learning?

Informal and Formal Learning

Learning experiences can be placed on a continuum from informal situations such as a conversation with a friend to formal environments such as workshops and courses.

Informal Learning

Many school and public library, museum, and nature center activities are informal settings for learning.

Many school and public library, museum, and nature center activities are informal settings for learning.

Gilton (2012, 1) points out that

"public librarians have always instructed their patrons on the use of information, but their style is so informal, personal, and indirect, and basic and so tied to guidance, it is not always recognized as instruction, either by public librarians or by their peers in academic settings."

Informal learning is often associated with free-choice, out-of-school inquiries. However it can also occur in classroom settings when students seek out learning opportunities beyond formal assignment requirements. Children may learn by reading to the library cat, enjoying a book in the leisure reading area, or participating in a discussion at recess. Adults may learn through discussions with peers at the library cafe, conversations at public library events, or interactions with colleagues.

Daniel Callison (2003) described the Chautauqua Institute founded in the 1870s as an experiment in vacation-based, out-of-school learning. Created as an environment where people of all ages could come together to share their talents, knowledge, and interests, this informal learning continues today in the form of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle book club. This free-learning approach was been embraced by libraries around the world.

Librarians can build environments that promote informal learning. For instance, a traditional bulletin board could be turned into an interactive area to explore new ideas. Displays associated with course content can extend subject area learning. Use "how-to" handouts and "read-alike" fliers to facilitate informal learning.

The photo below shows an interactive bulletin board from Newton Free Library. Young people read and share books based on the idea of One World, Many Stories.

Formal Learning

A primary mission of schools is to help learners become independent, productive thinkers. Libraries are essential in this mission. For learning to be efficient, efficient, and appealing, people need to be information literate.

Learning experiences come in many forms. More formal learning environments may involve self-guided, small group discussions, demonstrations, and lectures.

Learning experiences come in many forms. More formal learning environments may involve self-guided, small group discussions, demonstrations, and lectures.

These learning experiences often involve a facilitator that guides the learner through the experience. This instructional support can come from a librarian, teacher, trainer, volunteer, mentor, and/or parent.

Each student is unique.

Each teacher is unique.

The key is to match learning needs with effective instructional approaches.

Try It!

Try It!

Think about a library you know well. Create two lists.

First, list the informal learning experiences available for users.

Second, list the formal learning opportunities.

Then, consider the potential.

What other informal and formal learning experiences could be provided? Why? In what areas?

Pedagogy & Andragogy

Pedagogy is the art and science of teaching. It's generally associated with preschool through college-level learning.

Pedagogy is the art and science of teaching. It's generally associated with preschool through college-level learning.

- The art aspect involves creative components such as designing engaging experiences and producing appealing materials.

- The science element involves applying learning theories and domains of learning to produce effective and efficient instruction.

Blanchett, Powis, and Webb (2012, 6) stress that

"it can be tempting to believe that there is a 'right way' of teaching a specific topic, but this is not true: there are many effective ways of teaching the same content... effective teaching is a balance between applying your knowledge of pedagogy and sensitive to immediate circumstances."

Andragogy is the art and science of teaching adult learners. First identified in the early 19th century, it was developed as a theory of adult education by Malcolm Knowles in the mid 20th century. He asserted that adult learners come to the classroom with a different set of needs and expectations than children and young adults. However, Knowles also notes that pedagogy and andragogy represent a continuum from teacher to student-directed learning depending on the situation.

Andragogy is the art and science of teaching adult learners. First identified in the early 19th century, it was developed as a theory of adult education by Malcolm Knowles in the mid 20th century. He asserted that adult learners come to the classroom with a different set of needs and expectations than children and young adults. However, Knowles also notes that pedagogy and andragogy represent a continuum from teacher to student-directed learning depending on the situation.

Throughout this course we'll use two sets of examples. First, we'll explore examples related to information literacy and inquiry-based learning situations. Second, we'll examine content-areas scenarios and applications such as the needs of history students or health care workers.

Adults learners are...

- Questioners. Adults learn based on need. They want to know that what they are doing matters (a) in real-life and (b) on the test. They want to see relevance.

Example: Introduce a problem-based activity with a real-world example and/or test item.

Stress that locating evidence to support an argument is a skill needed both in school and in the workplace.

Point out that you need to know the vocabulary of the human body in order to describe patient symptoms.

- Self-Directed. Adults need to be in control of the learning process. They want to make decisions about their learning. Whenever possible, instructors should be facilitators rather than information givers.

Example: When possible, provide choice and opportunities to discover content.

Provide students with different types of periodicals to explore. Ask them to categorize them. Then, discuss the idea of scholarly journals versus popular magazines.

Rather than lecturing about drug interactions, provide students with a fact sheet and a set of empty bottles and other items to discuss. Then, check and comment on their work.

- Experience Rich. Adults come to class with a wide range and depth of experiences. Use this knowledge as a frame of reference for new learning, while remembering that students may come with misconceptions.

Example: Ask for students to share experiences and concerns while looking for predispositions and bias.

Ask students about their experiences dealing with information overload.

Discuss student experiences and thoughts about child abuse before describing the signs. Looks for preconceived ideas about this topic.

- Real-World Focused. Lecturing doesn’t equal learning. Students need to be active to learn. They want to see the connection to real-world situations. They need to build new experiences while constructing knowledge.

Example: Build authentic activities, questions, and discussions into lectures.

Ask students to choose a celebrity, sports figure, or other current person in the news. Ask them to brainstorm ways to locate information about this person. Weave their topics and ideas into the discussion of reference materials.

Rather than discussing abstract examples, focus on a specific situation such as a tractor tipping over on a field worker.

- Task-oriented. They are life-centered and want to apply information immediately to real-life. Don’t separate theory and practice. Instead, build bridges with problem-based learning.

Example: Show a real-world application for each chunk of content or concept.

Discuss criteria for evaluating websites within the context of a real-world example using a current social issues topic.

Introduce the signs of stroke using the FAST method and match it with a role-playing activity. Use "Act FAST" for recognizing signs of stroke.

- Internally Motivated. Increased satisfaction, self-esteem and quality of life are more important that money and promotions. Show students why course content matters.

Example: Provide praise, opportunities for success and real-world connections.

Talk to students about how instant access to information can save their job.

When introducing a strategy, talk about how many lives are saved by EMT intervention such as the YouTube EMT Saves Lives.

Try It!

Try It!

Read the three instructional situations below.

Pick ONE of the six characteristics of adult learners above. Keep in mind that high school and college students are transitioning into the adult category. Describe how you would adapt instruction to address that characteristic.

Situation 1: The instructor uses PowerPoint bullets to list facts about the "Opposing Viewpoints" database then gives students a handout to read.

Situation 2: The instructor talks about how to use self-checkout system then gives a multiple choice quiz.

Situation 3: The instructor writes the types of periodicals on the chalkboard, defines each type of periodical, and tells students to take notes.

Information Inquiry

Inquiry is the process of formulating questions, organizing ideas, exploring and evaluating information, analyzing and synthesizing data, and communicating findings and conclusions. It's the type of activity that children and adults are asked to do every day. Unfortunately, not everyone is well-prepared to deal with the demands of a fast-paced, technology-rich world containing endless opportunities, choices, perspectives, and conflicts.

Callison (2006, xiii) notes that we often combine types of inquiry together. However each aspect requires specific skills, resources, and tools. Some areas of inquiry include:

- Critical - using text and data for current local and national social action

- Scientific - testing the value of information to solve problems

- Graphic - extracting information from and presenting information in visual formats such as political cartoons, diagrams, maps, photos, charts, tables, and multimedia

- Historical - using oral history to tell local stories and critical examination of primary resources

- Critical History - gaining a greater understanding of our true heritage; who are the real heroes and heroines, and what is real social history?

- Personal - becoming aware of how we grow and mature as inquirers

- Virtual - accelerating inquiry through modern communication technologies and defending arguments in an open forum

- Media - how information pressed on us through popular mass communication must be understood and managed in our personal and professional lives

- Social/Democratic - determining the value of information as evidence used in dialogue

In Empowered Learning in Curriculum Connections through the Library edited by Stripling and Hughes-Hassell, Violet H. Harada (2003, p. 62) states:

"We need to make a lifelong commitment to inquiry. Although the ability to think critically has always been important, it is imperative for the citizens of the twenty-first century. The decisions that our students make as individuals and as a society on issues that range from preserving and sustaining our environment to combating the atrocities of racism and terrorism will affect all future generations. The information to make responsible choices is at their fingertips. However, if young people cannot think intelligently and sensitively about the myriad issues confronting them, then they are in danger of having all of the answers, but still not understanding what these solutions mean."

Student information scientists of all ages can participate in inquiry-based experiences.

Try It!

Try It!

Go to Snapshots to Stimulate Thinking.

To understand the role of the librarian in teaching information skills, it's helpful to explore examples. Rather than completed cases, these examples are simply "snapshots" intended to stimulate your own ideas.

Think about a case that reflects the type of learning that you think is important for today's 21st century citizens.

Information Literacy

The definition of literacy has evolved over the past century. Most dictionaries define literacy as the ability to read and write. Today the definition has been expanded. Many now consider literacy to be the ability to locate, evaluate, use, and communicate using a wide range of resources including text, visual, audio, and video sources.

The definition of literacy has evolved over the past century. Most dictionaries define literacy as the ability to read and write. Today the definition has been expanded. Many now consider literacy to be the ability to locate, evaluate, use, and communicate using a wide range of resources including text, visual, audio, and video sources.

According to Barbara Stripling in Curriculum Connections through the Library (2003, p. 9),

"not only are literacy and inquiry related through common thinking skills, but they are both inextricably related to content. Neither can be mastered out of context (students learn to comprehend and inquire when they are engaged in learning about concepts that matter to them)."

In Building A Nation of Learners , the authors discuss the needs for changes in our educational system that support 21st century skills. These skills include:

- Focusing education on the lifelong learning skills and attributes needed for a nation of learners.

- Creating content that is challenging, motivating, and relevant.

- Encouraging learning through more interaction and individualization.

- Increasing opportunities and access to education.

- Adapting objectives to specific outcomes and certifiable job-related skills.

Read!

Read!

Read The Whole Student: Cognition, Emotion and Information Literacy by Miriam L. Matteson (2014). Think about the many factors that impact student information literacy.

The History of Information Literacy

The term "information literacy" can be traced back to the mid 1970s. In 1974, Paul Zurkowski, president of the Information Industry Association began using the term (Eisenberg, Lowe, & Spitzer, 2004).

During the 1980s, many researchers focused on the identification of knowledge and skills needed by information users. This led to the development of information processing and research process models aimed at K-12 students.

In 1989, the American Library Association's Presidential Committee on Information Literacy defined an information literate individual as a someone who is able to

"recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate and use effectively the needed information... Ultimately, information literate people are those who have learned how to learn. They know how to learn because they know how knowledge is organized, how to find information and how to use information in such a way that others can learn from them. They are people prepared for lifelong learning, because they can always find the information needed for any decision or task at hand. " (ALA, Presidential Committee on Information Literacy Final Report, 1989).

The importance of information literacy was acknowledged by many education and library organizations during the 1990s including the National Education Association and the American Association of School Administrators.

In a 2005 proclamation, UNESCO describes information literacy and lifelong learning as the

"beacons of the Information Society, illuminating the courses to development, prosperity and freedom. Information literacy empowers people in all walks of life to seek, evaluate, use and create information effectively to achieve their personal, social, occupational and educational goals. It is a basic human right in a digital world and promotes social inclusion in all nations."

Renewed interest has been expressed in developing information literacy. In 2009, Obama proclaimed the first National Information Literacy Awareness Month to be held in October each year.

Information Literacy Defined

National and international organizations have defined information literacy in similar ways.

The Association of College & Research Libraries with ALA defined information literacy as

“recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information.”

ACRL, in its statement on Information Literacy and Competency Standards for Higher Education states:

Information literacy also is increasingly important in the contemporary environment of rapid technological change and proliferating information resources. Because of the escalating complexity of this environment, individuals are faced with diverse, abundant information choices in their academic studies, in the workplace, and in their personal lives. Information is available through libraries, community resources, special interest organizations, media and the Internet, and increasingly, information comes to individuals in unfiltered formats, raising questions of its authenticity, validity, and reliability.

… Information literacy forms the basis for lifelong learning. It is common to all disciplines, to all learning environments, and to all levels of education. It enables learners to master content and extend their investigations, become more self-directed, and assume greater control over their own learning. An information literate individual is able to:

- determine the extent of information needed

- access the needed information effectively and efficiently

- evaluate information and its sources critically

- incorporate selected information into one's knowledge base

- use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose

- understand the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information

- access and use information ethically and legally

Similar definitions can be found from organizations around the world.

The Australian Library and Information Association has defined information literacy

"as the ability to recognise the need for information and to identify, locate, access, evaluate and effectively use the information to address and help resolve personal, job related, or broader social issues and problems".

The UK's Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) defines information literacy as

"knowing when and why you need information, where to find it, and how to evaluate, use and communicate it in an ethical manner."

CILIP states information literate individuals have an understanding of:

- A need for information

- The resources available

- How to find information

- The need to evaluate results

- How to work with or exploit results

- Ethics and responsibility of use

- How to communicate or share your findings

- How to manage your findings

Try It!

Try It!

Organizations from around the world have developed their own definitions of information literacy. Now is your chance.

Browse the definitions from these groups, then write your own definition.

People spend endless hours refining these definitions. Why is having a precise definition important?

In recent years, librarians have begun to rethink their focus on information literacy. Is a formal information literacy program necessary? Or, should these skills be woven into the fabric of the entire university system?

Read!

Read!

Read Cowan, Susanna M. (2014). Information literacy: the battle we won that we lost? portal: Libraries and the Academy, 14(1), 23-32. Available to IUPUI students.

What are your thoughts on information literacy instruction?

Associated Literacies

Although library and information professionals generally focus on information literacy, there are many other closely connected literacies to consider.

Over the past few decades many "new literacies" have been identified. For instance, NCREL's enGauge (2003) identify eight digital age categories:

- Basic Literacy

- Scientific Literacy

- Economic Literacy

- Technological Literacy

- Visual Literacy

- Information Literacy

- Multicultural Literacy

- Global Awareness

Along with information and technology related literacies, many people have focused on other categories of literacy such as communication literacy, productivity literacy, content literacy, and critical literacy.

Not everyone agrees on the need to distinguish these new literacies. For example, some people interpret it as way to justify library positions or a "new subject" that will be a burden to teachers.

Read!

Read!

Read Is There a Difference Between Critical Thinking and Information Literacy? A Systematic Review 2000-2009 by John Weiner (2011).

Consider how information literacy and critical thinking are connected.

Content Literacy

Content literacy involves the integration of strategies and experiences the build understandings related to a particular topic rather than simply acquiring large amounts of information.

Content literacy involves the integration of strategies and experiences the build understandings related to a particular topic rather than simply acquiring large amounts of information.

A person who is content literate has a heightened awareness and use of the organization and structure of distinct texts in diverse fields of study and knows how to read in strategic ways to obtain important knowledge from them.

Even understanding a simple weather broadcast requires basic content literacy related to science.

Callison (2006, 340) notes that content literacy involves the integration of strategies and experiences in two ways:

- Effective strategies for reading, writing, speaking, listening, and thinking are more likely to develop more naturally and easily when task are integrated than when isolated.

- Meaning is enriched across subjects and experiences when content literacy embraced discourse and text from several distinct disciplines.

Creative Literacy

Creative thinking focus on the development of inventive ideas. Creative thinking involves creating something new or original. It's the skills of flexibility, originality, fluency, elaboration, brainstorming, modification, imagery, associative thinking, attribute listing, metaphorical thinking, forced relationships. The aim of creative thinking is to stimulate curiosity and promote divergence.

Inventive Thinking is comprised of the following 'life skills':

- Adaptability/Managing Complexity: The ability to modify one’s thinking, attitude, or behavior to be better suited to current or future environments, as well as the ability to handle multiple goals, tasks, and inputs, while understanding and adhering to constraints of time, resources, and systems (e.g., organizational, technological)

- Self-Direction: The ability to set goals related to learning, plan for the achievement of those goals, independently manage time and effort, and independently assess the quality of learning and any products that result from the learning experience

- Curiosity: The desire to know or a spark of interest that leads to inquiry

- Creativity: The act of bringing something into existence that is genuinely new and original, whether personally (original only to the individual) or culturally (where the work adds significantly to a domain of culture as recognized by experts)

- Risk-taking: The willingness to make mistakes, advocate unconventional or unpopular positions, or tackle extremely challenging problems without obvious solutions, such that one’s personal growth, integrity, or accomplishments are enhanced

- Higher-Order Thinking and Sound Reasoning: Include the cognitive processes of analysis, comparison, inference/interpretation, evaluation, and synthesis applied to a range of academic domains and problem-solving contexts (enGauge, 2003, p. 27)

Skim Teaching for Creativity: Building Innovation through Open-Inquiry Learning by Jean Sausele Knodt.

To learn more, explore Creativity & Standards: Amazing Authentic Approaches by Annette Lamb for lots of examples.

Critical Literacy

Critical literacy places emphasis on understanding how to identify issues, gain a context for the arguments surrounding an issue, and move through information as intelligent selectors of evidence in order to dialogue, debate, and propose change.

Critical literacy places emphasis on understanding how to identify issues, gain a context for the arguments surrounding an issue, and move through information as intelligent selectors of evidence in order to dialogue, debate, and propose change.

From cereal advertisements on television to opinions from friends, young people are bombarded with information and perspectives. To become good decisionmakers, students need to be able to think critically.

Critical thinking involves logical thinking and reasoning including skills such as comparison, classification, sequencing, cause/effect, patterning, webbing, analogies, deductive and inductive reasoning, forecasting, planning, hypothesizing, and critiquing.

While critical thinking can be thought of as more left-brain and creative thinking more right brain, they both involve "thinking." When we talk about HOTS "higher-order thinking skills" we're concentrating on the top three levels of Bloom's Taxonomy: analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Critical thinking involves identifying evidence, reasoning, and implications. John Dewey (1909) referred to critical thinking as reflective thinking. He defined it as "active, persistent, and careful consideration of a belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds which support it and the further conclusions to which it tends."

Edward Glaser (1941) added that critical thinking is

"an attitude of being disposed to consider in a thoughtful way the problems and subjects that come within the range of one's experience and a skill in applying those methods."

Glaser identified a range of abilities including recognize problems, gather information, recognize assumptions, use clear language, interpret data, appraise evidence, recognize relationships, draw conclusions, test conclusions, reconstruct patterns, and render judgments.

In 1989, Robert Ennis stated that critical thinking is "reasonable, reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do."

More recently, Michael Scriven (1997) stated that critical thinking is "skilled and active interpretation and evaluation of observations and communications, information and argumentation."

To learn more, explore Teacher Tap: Creative and Critical Thinking.

Data Literacy

Increasingly, students need to be able to use scientific, statistical, and technical source data.

Calzada and Marzal (2013) have advocated for data literacy in school, public, and academic libraries. They identify the following specific competencies including understanding data, finding and/or obtaining data, reading, interpreting and evaluating data, managing data, and using data.

Media Literacy

Media literacy is being able to critically evaluate media, use media, and produce one's own communication through the use of visual and audio media.

Media literacy is being able to critically evaluate media, use media, and produce one's own communication through the use of visual and audio media.

"Media Literacy is the ability to decode, analyze, evaluate, and produce communication in a variety of forms" (Definition of the Trent Think Tank on Media Literacy, Ontario, Canada, 1989).

Many quality resources and organization provide information about media literacy including the Media Smarts, Media Literacy Clearinghouse, National Association for Media Literacy and Project Literacy Among Youth.

Technology and Digital Literacy

Some people consider technology and digital literacy to be a subset of information and visual literacy. However, others consider the digital format unique.

Paul Gilster, author of Digital Literacy, defines digital literacy as the ability to understand, evaluate and integrate information in multiple formats via computer and the Internet.

Educators have developed an evolving list of computer and technology skills. Most experts agree that it's important that students learn generic skills that can be transferred as software and hardware changes.

Educators have developed an evolving list of computer and technology skills. Most experts agree that it's important that students learn generic skills that can be transferred as software and hardware changes.

Transliteracy

Transliteracy is "the ability to read, write and interact across a range of platforms, tools and media from signing and orality through handwriting, print, TV, radio and film, to digital social networks.” - Transliteracy.com

Visual Literacy

Visual literacy is the ability to understand and use images. This includes to think, learn, and express oneself in terms of images. Photographs, cartoons, line drawings, diagrams, concept maps, and other visual representations are all important in visual literacy.

In the 1960s, IVLA (International Visual Literacy Association) was formed to help people learn more about visual learning, visual thinking, and visual language. Hattwig and others (2013) have recently argued for the importance of visual literacy in our current visual culture.

Children learn to read pictures before they read words. Unfortunately, we often stop visual teaching once children can read. In this information age, it's important to continue to help people interpret the visual world around them. From books and television to billboards and animation, students are bombarded with visuals. Visual literacy is a critical life skill.

Visual resources are important in all content areas. In social studies, students can learn about history by analyzing historical photographs and posters. Student use photographs to explore scientific processes and relationships. Photographs can stimulate emotions for creative writing.

Explore some of the following ideas from teachers (Thanks to W. Kovach, C. Blake, A. Ashton, S. Sandor):

- Scan and use pictures that correlate to poems you are teaching.

- Create a slide show of photographs representing the setting or time period of the novel the class is reading.

- Ask students to take a digital camera photograph that represents the setting of a poem such as Robert Frost's Stopping By The Woods On A Snowy Evening.

- Create visual representations for poems, songs, book chapters, or characters.

- Create maps related to novels such as maps of the city of Paris and London when reading A Tale of Two Cities.

- Create political or satirical cartoons related to content in any subject area.

- Use charts, graphs, map and photos to show population growth, weather and traffic patterns, or the spread of disease.

- Create a slide show of historical photographs and ask students to write the narrative for a project on the Civil War, the Holocaust, Labor Movement, or Civil Rights Movement.

- Use visuals from nature in teaching math. In a unit on fractals use the Earth's natural formations such as Grand Canyon, bee hives, and snowflakes.

- There are many ways to incorporate visual elements when studying a novel. For example suggested when reading Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse that teacher might use historical photographs from the time period to better understand the free verse poem.

Many children learn best through the visual channel.

Many teachers are finding that graphic novels are a great way to motivate their students. For example, Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award. Spiegelman metaphorically uses animals to retell the story of his father’s experience as a Jewish prisoner in a WW II concentration camp. Students of all reading levels will be intrigued by his father’s experience, and the comic book-like graphics will appeal to readers for multiple reasons, one being its use of visual literacy. (Thanks to E. Kaiser for this idea)

Many teachers are finding that graphic novels are a great way to motivate their students. For example, Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award. Spiegelman metaphorically uses animals to retell the story of his father’s experience as a Jewish prisoner in a WW II concentration camp. Students of all reading levels will be intrigued by his father’s experience, and the comic book-like graphics will appeal to readers for multiple reasons, one being its use of visual literacy. (Thanks to E. Kaiser for this idea)

When teachers use graphic novels during instruction, it keeps the students more actively involved in the reading process; they must not only understand the text, but be able to mesh the words with their interpretations of the graphics as well.

You might also get students involved with writing their own comics or graphic novels. Or, provide students with photographs they might integrate into the their writing.

Consider using film adaptations of books as a way to provide visual resources for students. Some of the best movies are made by groups such as A&E Biography, the Discovery Channel, and Hallmark. Explore Books and Movies in the Classroom from Multimedia Seeds.

Explore the Graphic Inquiry online workshop to learn more about visual literacy and graphic representations.

Watch and Try It!

Watch and Try It!

Watch Martin Scorsese discuss the importance of visual literacy at edutopia.

Visual literacy is one of many

literacies associated with information literacies.

How do all of these "associated literacies" fit together?

Create a diagram that shows the overlapping definitions.

Place information literacy in the middle of the diagram and surround it with these related topics.

What's the responsibility of library and information professionals in addressing this wide range of literacies?

Read!

Read!

Read Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy by Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi E. Jacobson (2011).

Information Fluency

Information fluency is the ability to apply the skills associated with information literacy, computer literacy and critical thinking to address and solve information problems across disciplines, across academic levels, and across information format structures (Callison, 2006).

Information fluency is the ability to apply the skills associated with information literacy, computer literacy and critical thinking to address and solve information problems across disciplines, across academic levels, and across information format structures (Callison, 2006).

In Key Word: Information Fluency, Callison (2004) stresses that "an information literate person is able to:

- determine the extent of information needed

- access the needed information effectively and effectively

- evaluate information and its sources critically

- incorporate selected information into their knowledge base

- use information to accomplish a specific purpose

- understand the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding access and use

- of information

- access and use information ethically and legally

According to The Associated Colleges of the South, using critical thinking skills and appropriate technologies, information fluency integrates the abilities to:

- collect the information necessary to consider a problem or issue

- employ critical thinking skills in the evaluation and analysis of the information and its sources

- formulate logical conclusions and present those conclusions in an appropriate and effective way

Content area librarians other educators must coordinate their efforts to achieve information fluency in their learners.

Content area librarians other educators must coordinate their efforts to achieve information fluency in their learners.

Example: a language arts or social studies teacher might create an assignment that asks students to interview an adult about their career. This project might address a specific subject area standard. However without information skills related to conducting an effective interview, students will be unable to reach their content-area goal. In the same way, a librarian can ask students to memorize interviewing techniques, but these strategies are meaningless without an authentic project. The skilled librarian sees the importance of collaboration and development of a range of skills and experiences to promote information fluency.

In "Promoting Information Fluency", Overholtzer and Tombarge (2003) stress the importance of providing a context for information skills instruction at the college level. In their study, information skills were infused into a research-intensive Quantitative Analysis class. They found that this approach "allows the skills to be taught within the context of a discipline in a way that matches how students like to learn." (58).

Information Exploration Hierarchy

Information fluency is the highest level of information evaluation and management for the mature information literate person relative to their age and ability levels. At the most sophisticated level, the mature learner moves efficiently and effectively across a variety of information systems, databases and communication technologies. This person has the accomplished background to assimilate, manage, apply or even create emerging technologies to address information issues yet to be identified.

Information inquiry is a teaching and learning process based on information and media literacy elements of questioning, exploration, assimilation, inference, and reflection. These elements are common to most linear models for information search and use, but represent the cyclical processes necessary to address new questions that arise in any investigation. Techniques involve a combination of ancient Socratic questioning methods and modern technologies to create exciting real and virtual learning environments for students and teachers to think and act critically and creatively. Learning is often based on authentic projects, issues and reflections that are interwoven among personal, academic and workplace information needs.

Information and media literacy involve understanding how to evaluate and place value on information that is either sought in a systematic manner to address personal, academic or workplace needs. The ability to understand, evaluate and manage information constantly presented in a mass communication world.

Information skills involve understanding how to identity and extract information to address a basic information need; usually in an academic setting.

Library skills focuses on how to locate and cite resources available in the local library.

Visualizing Information Fluency

As the instructional librarian designs inquiry-rich projects that promote information fluency, they must consider the connections between information literacy, technology literacy, critical and creative thinking, and content literacy.

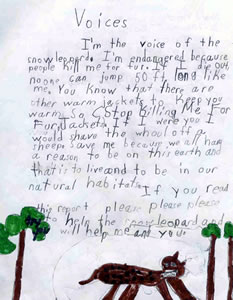

Example: The project titled "Voices," (on the right) shows how the student was engaged in a creative approach to understanding endangered animals. Rather than simply writing a traditional animal report, the student is asked to be creative in their thinking about the plight of their chosen endangered animals. What would it be like to be this animal? Why are these animals threatened?

In Key Word: Information Fluency, Callison (2004) states that information fluency involves the abilities to

In Key Word: Information Fluency, Callison (2004) states that information fluency involves the abilities to

- transfer information and media literacy skills to address new information need situations

- employ the use of modern computer technologies to obtain, select, analyze, infer conclusions from information

- employ critical thinking to derive evidence from information and creative thinking for the expression and application of that evidence to decisionmaking

- move across multiple strategies and evaluation levels in order to address

- different information needs found in academic, workplace and personal environments

Click the student project on the right to enlarge the visual. Click the close box to return to this page.

Interdisciplinary Approaches

Inquiry is an approach that can be applied in every content area.

Over the past twenty years, the role of the librarian has changed dramatically. Library programs have moved from teaching isolated "library skills" to an integrated approach focusing on meaningful, information inquiry projects that connect to standards across the curriculum.

Librarians have the opportunity to bring teachers and content areas together through the development of interdisciplinary approaches to learning.

Example: Connect your industrial technology teacher and mathematics teacher for a practical exploration of engineering and technology.

In the chapter Empowered Learning in Curriculum Connections through the Library edited by Stripling and Hughes-Hassell, Violet H. Harada explores thinking across the curriculum and envisions what these information skills look like in various disciplines (2003, p. 45-46):

"In language arts - literacy appreciation and analysis require strategic use of language, including being able to predict, validate, and synthesize. They also encourage analysis from multiple points of view and perspectives and the ability to identify bias and stereotyping. Students are immersed in both literary and nonliterary modes of information. Active engagement is critical.

In social studies - historical analysis involves formulating questions, obtaining data from sources, testing these sources for their accuracy and authority, and detecting and evaluating propaganda and distortion. Students develop comparative and causal analyses and construct sound historical arguments. They use resources ranging from primary documents and artifacts to virtual field studies found on the Internet.

In mathematics - problem solving in mathematics challenges students to formulate problems, consider alternative strategies to solve them, and apply a strategy and verify the results. To accomplish these aspects of problem solving, they must be able to collect, organize, and describe data; construct, read, and interpret displays of data; and formulate and solve problems that involve data collection and analysis. Mathematical inquiry provokes students to make sense of ideas in relation to one another and to the everyday world. The focus is on conceptual understanding, multiple representations, and connections.

In science - scientific inquiry necessitates that students understand key questions and concepts that guide scientific investigations. They must be able to develop testable hypotheses, design and conduct the investigations, formulate and revise explanations and models using logic and evidence, and communicate and defend their findings. Students use a wide range of tools and make choices among alternatives. Carefully planned experiments can proceed in a predictable fashion or yield startling data that lead to new questions and investigations. The process is not random; it follows a purposeful sequence of testing, data collection and analysis, and drawing of conclusions.

In information inquiry - information searching and use assume that problems and issues investigated require student engagement with information in different formats and for different purposes. Students must be able to articulate the focus of their information search, generate questions that probe the problem, consider alternative strategies to locate and retrieve data, and evaluate their value and relevance. Students also need to explore organizational schemes that help them store and use their information and to home their expertise with different communication formats."

Read!

Read!

Read Thinking Across Several Content Areas (PDF) from Violet H. Harada in Empowered Learning in Curriculum Connections through the Library edited by Stripling and Hughes-Hassell.

Violet Harada challenges school librarians to examine the curriculum from the perspective of thinking processes. She stresses the importance of self-assessment and notes that "many of us may discover that we have focused largely on tasks at the mechanical levels of performance rather than at levels requiring manipulation of information and ideas (2003, Curriculum Connections through the Library, p 48).

Harada's examples of traditional tasks:

- Using an online catalog

- Identifying the physical components of a resources

- Locating materials within a specific library

- Using an organizational scheme to take notes

- Creating a bibliography

Harada suggests that school librarians devise learning experiences that help students attack deeper aspects of an investigation.

Harada's examples of thinking strands:

- Perception and Recognition - honing question-making skills

- Storage and Retrieval - distinguishing relevant from irrelevant information

- Organization and Transformation - selecting the most appropriate information for the particular need

- Reasoning and Utilization - creating tangible evidence

- Metacognition - reflecting on how on acquires knowledge... thinking about thinking

According to Harada (2003, Curriculum Connections through the Library, p 50),

"effective thinkers are disposed to explore, to question, to probe new areas, to seek clarity, and to be open to different perspectives.. students are not only problem-solvers but problem-posers. They develop a sense of ownership for the knowledge they are acquiring and are responsible for their own and others' learning. Students listen and question, visualize and connect, examine and challenge. They collaborate and support others. They are teachers as well as learners."

Try It!

Try It!

Explore the Interdisciplinary Learning in Your Classroom free, online workshop from Disney Learning Partnership.

Regardless of whether you're interested in schools, colleges, public, or other settings, a content-area emphasis is essential. Learners need information skills to be placed in a meaningful, real-world context using either a personal area of interest or an academic connection.

How will you make learning meaningful and move students from simply acquiring information skills to becoming information fluent?

Resources

Abilock, Debbie (September/October 2004). Beginner's Blind Spot. KnowledgeQuest, 33(1).

American Library Association (1989). Presidential Committee on Information Literacy. Final Report. Chicago: American Library Association. Available: http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential

Asselin, Marlene & Doiron, Ray (January 2008). Towards a Transformative Pedagogy for School Libraries, School Libraries Worldwide, 14(2).

Building A Nation of Learners

Brown, David (1999). Information Fluency: What? Why? How? - PowerPoint Presentation

Bruce, Bertram C. & Bishop, Ann P. (May 2002). Using the Web to Support Inquiry-Based Literacy Development. Reading Online: Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(8).

Callison, Daniel (September 2003). Informal Learning. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 20(1), 33-8.

Callison, Daniel (Spring 2004). Key Word: Information Fluency. School Library Media Activities Monthly.

Callison, Daniel. (2006) Key Words, Concepts and Methods for Information Age Instruction: A Guide to Teaching Information Literacy. LMS Associates.

Calzada Prado, J., & Marzal, M. Á. (2013). Incorporating data literacy into information literacy programs: Core competencies and contents. Libri: International Journal of Libraries & Information Services, 63(2), 123–134.

Center for Inquiry-based Learning from Duke University. A group developing exercises and training teachers in the use of multidisciplinary, hands-on, minds-on, discovery methods for teaching science.

Critical Thinking Consortium. Organization promoting critical thinking

Doyle, C. (1994). Information Literacy in an Information Society. Available at Google Books.

Eisenberg, M.B., Lowe, C.A. & Spitzer, K.L. (2004). Information Literacy: Essential Skills for the Information Age. Libraries Unlimited.

Gilton, Donna L. (2012). Lifelong Learning in Public Libraries. Scarecrow Press.

Gordon, Carol A. (1999). Students As Authentic Researchers: A New Prescription for the High School Research Assignment. School Library and Media Research, 2.

Harada, V.H. (2003). Empowered learning. In B. Stripling and S. Hughes-Hassell (eds.), Curriculum Connections through the Library. Libraries Unlimited.

Harvey, Phyllis J., & Goodell, Karen J. (Spring 2008). Development and evolution of an information literacy course for a doctor of chiropractic program. Communications in Information Literacy, 2(1), 52-61.

Hattwig, D., Bussert, K., Medaille, A., & Burgess, J. (2013). Visual literacy standards in higher education: New opportunities for libraries and student learning. portal: Libraries & the Academy, 13(1), 61-89.

Hays, Lyn (1999). Information Literacy: Seeking Meaning With Actions, Thought, and Feelings.

Hudspith, Bob. Teaching the Art of Inquiry. Overview to inquiry and teaching the art of inquiry.

The Keys to Inquiry from Harvard. Provide opportunities for students to learn that inquiry and their own experiences can help them achieve a deeper understanding of their world.

Kirton, Jennifer & Barham, Lyn (2005). Information literacy in the workplace. Australian Library Journal, 54(4).

Knowles, Malcom. (1980). The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy. 2nd ed. Association Press.

Knowles, Malcolm; Holton, E. F., III; Swanson, R. A. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (6th ed.). Elsevier.

Loertscher, David V., and Blanche Woolls (1999). Information Literacy: A Review of the Research: A Guide for Practitioners and Researchers, Hi Willow Research and Publishing. Review of research on information literacy.

Mancall, Jacqueline C., Aaron, Shirley L. & Walker, Susan A. (1986). Educating Students to Think: The Role of the School Library Media Program. SLMQ, 5(1).

Manzo, A. V. & Manzo, U. C. (1997). Content Area Literacy: Interactive Teaching for Active Learning. Merrill.

McAdoo, Monty L. (2012). Fundamentals of Library Instruction. ALA Editions.

McKenzie, Jamie. Questioning.org. Articles and activities related to questioning.

Media Literacy Starting Points: Tips for Fostering Critical Thinking by Sara Armstrong.

MindTools. Career-related skills and resources.

NCREL (2003). enGauge.

Obsborne, Antony (July 2011). The Value of Information Literacy: Conceptions of BSs Nursing Students at a UK University. Available: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/14577/1/A_Osborne_final_thesis.pdf

Overholtzer, Jeffrey & Tombarge, John (2003). Promoting information fluency. Educause Quarterly, 1, 55-58.

Project Information Literacy. Available: http://projectinfolit.org/practical/

Public Libraries: Impact of Public Libraries on Students and Lifelong Learners (October 2012). New York Comprehensive Center.

Shapiro, Jeremy J. & Hughes, Shelley K. (March/April 1996). Information Literacy as a Liberal Art. Educom Review.

Sheingold, Karen (1987). Keeping children's knowledge alive through inquiry. School Library Media Quarterly, (2), 80-85.

Stephens, E. C. & Brown, J. E. (2000). A Handbook of Content Literacy Strategies: 75 Practical Reading and Writing Ideas. Christopher-Gordon Publishers.

Stripling, Barbara (April 2010). Teaching students to think in the digital environnment: digital literacy and digital inquiry. School Library Monthly, 16-19.

Stripling, Barbara (2003). Inquiry-Based Learning. In Curriculum Connections through the Library, edited by Barbara Stripling and Sandra Hughes-Hassell. Libraries Unlimited, 3–40.

Thakkar, Umesh (November 2001). Extending Literacy Through Participation in New Technologies. Reading Online: Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 45(3).

Thompson, Nadine, Lewis, Sarah, Brennan, Patrick, and Robinson, John (June 2009). European Journal of Radiography, 1(2), 43047.

Tonjas. M. J., Wolpow, R. & Zintz, M. V. (1998). Integrated Content Literacy. McGraw-Hill.

UNESCO (2010). Toward Media and Information Literacy Indicators.

Weiner, J. (2011). Is There a Difference Between Critical Thinking and Information Literacy? A Systematic Review 2000-2009. Journal of information literacy, 5(2), pp 81-92.

What Teacher Educators Need to Know about Inquiry-Based Instruction by Alan Colburn. The author defines inquiry, reviews research about the topic, and discusses classroom implementation of inquiry principles.

Yakel, Elizabeth (October 2004). Seeking information, seeking connections, seeking meaning: genealogists and family historians. Information Research, 10(1). Available: http://informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper205.html